Judaism is one of the monotheistic religions, remarkable for its common origin with the world's two most prolific religions, Christianity and Islam. It originated in the Middle East over 3,500 years ago and is one of the oldest religions in the world that still exists today.

Understand

Since the Second Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in 70 C.E. (the First Temple having been destroyed much earlier by the Babylonians), Jewish worship and ritual has centered around the synagogue and the home. Synagogues are sometimes loosely called "temples," but the word "synagogue" is actually a Greek translation of the Hebrew words "Bet ha-Knesset," meaning a house of assembly, and is a place where Jewish people assemble to pray and study, but do not give sacrifices as Jews used to do at the Temple.

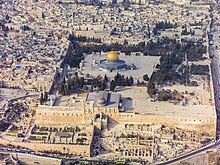

Relics of the Temple in Jerusalem, such as the Western Wall and the Temple Mount, are holy to Jews. Jewish worship on the Temple Mount is controversial among both Jews and Muslims and has been a flashpoint of conflict, so it is prohibited. The Western Wall functions essentially as an outdoor synagogue with a special feature: A tradition of writing prayers on paper and inserting them into cracks in the wall.

Graves, especially of tzaddikim (wise men), are holy to Jews and can also be places of pilgrimage. According to Jewish tradition, stones are often put there as a sign of grieve, reverence and the permanence of memory. Do not remove them.

Identity

The Jewish people are those whose spiritual ancestors are said to have received the Torah from Moses on Mount Sinai during the Exodus from Egypt, as described in the Biblical book of Exodus. One does not have to prove genetic descent from those who are said to have been present for that miracle to be Jewish. According to traditional Jewish belief, Moses received the Oral Law at the same time that he received the Torah, which is also called the Written Law. The Oral Law was first written down as the Mishna around 200 CE, but like the Torah, was transmitted orally for some time before that. Judaism is defined above all by laws, known as the 613 mitzvot (singular: mitzvah). The word mitzvot is often translated into English as "good deeds", but a more accurate translation is "commandments".

One thing to understand about the Jewish religion is that, unlike many other modern religions, it is inextricably linked to a particular people, the Jewish people. Traditional Jewish law defines as a Jew anyone who was born of a Jewish mother or converted to Judaism following the religion's laws on conversion. Converting to Judaism, while possible, is not easy. In fact, some interpretations of Jewish law require the applicant to be rejected three times before admission. Jews are of many hues, nationalities and ethnicities, yet recognize one another as belonging to a single people. In many ways, this is a continuation of the situation that existed in the ancient Middle East, when each nation had its own local god, but the crucial difference is that the Jewish people were able to survive the loss of their land and maintain a distinctive sense of identity and peoplehood as exiles who are citizens of the countries they live in but often share an overriding sense of commonality with other Jews, across differences in custom, nationality, ethnicity and appearance.

History

Ancient roots

The origins of the Jewish people are unclear. According to the book of Genesis in the Torah and Jewish tradition, the first Jew was Abraham, né Abram, the son of the Chaldean idol-maker Terach from Ur, now in Iraq. Historians and archaeologists tend to think of the Jews not as Mesopotamians who established themselves in the Land of Canaan (now Israel) but simply as a Canaanite sheep-herding people. One of the names of God mentioned in the Hebrew bible, El, is believed by historians and archaeologists to be the King of the Gods in the Canaanite pantheon. The second book of the Torah, Exodus, states that descendants of Jews who fled a drought in Canaan to find good pasture land in Egypt were enslaved, then liberated after God inflicted ten plagues on the Egyptians and sustained the Jews through 40 years in the Sinai desert on their way to conquering Canaan. The liberation from slavery in Egypt and the Exodus to the "promised land" of Israel are central to Jewish religion and identity and celebrated every year during the 8-day Passover (Hebrew: Pesach) holiday — and to a lesser extent, every other holiday — but historians and archaeologists have found no strong evidence that there was ever a large-scale enslavement of Jews in Egypt, nor a large-scale exodus of Jews from Egypt to Canaan, which would seem to contradict the Biblical account since the ancient Egyptians were known to be meticulous record keepers and would almost certainly have made a record of such a significant event. Regardless, it is in the Book of Exodus that one God is defined as the God of the Jews, and therefore, it is that book that marks the time when the Jewish people stopped being indiscriminately polytheistic and recognized the God in Heaven as their God. That does not mean, however, that Jews in ancient times quickly turned their backs on other gods, as you can tell from the Biblical prophets' constant inveighing against Jews' idolatries. In fact, most historians and archaeologists contend that the majority of Jews were polytheistic until after the Babylonian invasion of Jerusalem in the 6th century B.C., and that the Bible still contains vestiges of this polytheistic Judaism (for example, God referring to himself in both the singular and the plural) that was later edited out. Pottery findings in ancient Jewish tombs were found to have the inscription "Blessed be Yhwh and his Asherah". While Asherah is traditionally understood to refer to a pole in traditional Judaism and Christianity, historians and archaeologists understand her to be the consort of El in the Canaanite pantheon and the Goddess of Fertilty, who was subsequently adopted by the Jews as the consort of Yhwh (the 4-letter Name of God, also called by the Greek name, Tetragrammaton, which in Temple times was pronounced only by the High Priest and since the destruction of the Second Temple is no longer pronounced, with the word "Adonai", meaning "Lord", or a further gloss on that name substituted). In fact, many early Jewish homes were found to have Asherah figurines, suggesting that she was a popular goddess among the early Jews. Many archaeologists and historians believe that the original Temple of Jerusalem was not dedicated solely to the worship of Yhwh, but rather to the entire pantheon of gods in this early polytheistic Judaism.

The book of Exodus and the following books also mark the time when the Jews became a settled people occupying the Land of Canaan, rather than nomadic shepherds, and therefore represents the beginning of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. According to the Bible, at first there was a single Kingdom of Israel, ruled by kings including David and Solomon, who are recognized as among the great Jewish prophets. Later, the kingdom divided in two, with the southern Kingdom of Judah continuing to be ruled from the walled city of Jerusalem and the northern Kingdom of Israel being ruled from Shechem, which is now the Palestinian city of Nablus, and then Samaria, a bit further north and also now in the West Bank. The Bible contains many truths, but it is an anthology of sacred history, mythology and poetry, rather than a book that ever pretends to give an objective straight chronological historical narrative and modern archaeologists have found, for example, that King Ahab of the northern kingdom of Israel, condemned in the Bible for worshiping the pagan gods of his wife, Jezebel, presided over a prosperous and cosmopolitan nation that produced great art. King Omri, father of King Ahab was only glossed over in the Bible, though archaeological evidence suggests that he too ruled a prosperous and cosmopolitan nation, leaving behind the remains of great cities and steles erected to celebrate his achievements. On the other hand, modern archaeology has shown that Jerusalem was only a village at the time David and Solomon were supposed to have ruled, suggesting that both King David and King Solomon were at best village chiefs rather than great kings. Historians and archaeologists also contend that the two kingdoms of Judah and Israel were never united as described in the Biblical account, and had always been two separate kingdoms, and that the Bible as we know it today was written from the perspective of the Kingdom of Judah. Nevertheless, it is above all the prophets - not all of them attested to by history - who have had the most lasting influence on the character and history of Jews in the modern era, not the other kings of Israel and Judah, and not the priests of the Temple.

The Jewish nation was a small nation (and, at least eventually, two small nations) in the ancient Middle East, caught between the two superpowers, Egypt and Mesopotamia (Assyria and then Babylonia), which it did its best to play off against each other but sometimes failed. It had generally friendly relations with Phoenicia to its north, roughly corresponding to modern Lebanon, and intermittently close and hostile relations with Aram, corresponding to today's Syria.

Assyrian and Babylonian Exiles

Two ancient exiles were crucial in the history of the Jewish people and religion. The first was the Assyrian Exile, in the 8th century BCE. After the Assyrian Empire captured the northern Jewish kingdom of Israel, they scattered its inhabitants throughout the empire. To this day, there are people who say they are descended from the "lost tribes of Israel" that were victimized by this exile, and many modern-day Jews accept some of these claims as true, but because these Jews were so widely scattered, they were not able to maintain cohesion as a whole Jewish community in exile.

Babylonia captured the southern kingdom of Judah in 597 BCE. They destroyed the Temple and took the Jews in chains to Babylon. These exiles maintained cohesion, composing the Biblical Book of Lamentations, which includes the famous lines "If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither." After Babylonia was conquered by the Persian Emperor Cyrus in 539 BCE, he encouraged those Jews who wanted to do so to return to the Land of Israel and reestablish their Temple. The returning Jewish community was led by Ezra ha-Sofer, Ezra the Scribe, who was the first to write down the Torah, the five Books of Moses which had been passed down orally until then. Modern textual analysis suggests that the five books of Moses were originally composed by a number of different authors from different social backgrounds (think of the beginning of Genesis with its two vastly different creation myths, one sounding more like the tale of a peasant and the other sounding more like that of a priest) and some texts may have been written or vastly reformulated during the Babylonian exile, so it is possible to say that the Jewish religion as we now know it originates in that period.

The reestablished Jewish community in the Land of Israel eventually had to contend with Hellenistic influence. Many Jews were deeply influenced by Greek culture, while others resisted, and for a time, a group of anti-Hellenistic Jews called the Maccabees ruled Israel (the celebration of their victory over the Hellenistic King of Aram, Antiochus Epiphanes, in 165 BCE is one of the reasons for the holiday of Chanukah). When that dynasty degenerated, Judaea fell under Roman influence and was eventually made a Roman province. The civilization of the eastern part of the Roman Empire remained quite Hellenistic, and zealous Jews continued to resist and give Rome a big headache. It was as a result of the Roman anger over a Jewish rebellion (66-73 CE) that they destroyed the second Temple in 70 CE. A small band of offshoots of the Zealots continued to resist from high ground on top of a hill in Masada for 2-3 months, requiring some 15,000 Roman troops to defeat them, and this is celebrated by Jews to this day as an act of heroism, but this ultimately merely delayed the completion of the Roman victory. With the defeat of a final revolt led by the self-claimed messiah, Simon Bar Kochba (c. 132–136 CE "Bar Kochba" means son of the/a star and is most likely a name he gave himself), almost all the remnants of the Judean Jewish community were dispersed for centuries to come, and their land was renamed Syria Palæstina after the Philistines, the Jews' Biblical arch-enemies. The word for dispersion in Hebrew is Galut, and in Latin and English, it is called the Diaspora. Despite the frequently difficult and violent relations between Jews and the Roman empire, there was often a certain amount of admiration for the Jewish religion among Roman intellectuals and upper-class people and many authors (both Jews and non-Jews) mostly writing in Greek tried to reconcile Greek philosophy and Judaism, the best known among whom is Flavius Josephus, a veteran of the 66-73 CE revolt who was captured by the Romans and later wrote books about Jewish history, including that revolt. Both the Talmud and early Christian scripture arose with that background (in fact people like St. Paul were Hellenized Jews) and the popularity of certain "compatible" Greek philosophers like Aristotle in medieval Christian Europe is a late result of this intellectual movement.

Diaspora

Because the Diaspora lasted for thousands of years, not the 60-odd years of the Babylonian Exile, it necessitated great changes in Jewish identity and observance. Foremost among them was the loss of the Temple in Jerusalem, which has never been rebuilt since. This meant that the regular schedule of Temple offerings of animal and vegetable sacrifices described in the Bible could no longer take place, and the Kohanim - the priestly sub-tribe - no longer had a well-defined role to play in the community. Instead, the ritual functioning of the Jewish people was taken over by those called rabanim (singular: rav or rabbi), with prayer in beitim ha-knesset (houses of assembly, translated into Greek as synagogues), who acted as teachers, prayer leaders, and advisers on points of law. Notably, rabbis created the Talmud, the foremost book of Biblical commentary. The larger tribe the Kohanim are a subset of are called the Leviim (Levites), and they provided the music in the Temple, so some of them presumably continued to chant in the new Temple-less context, passing chants down from one cantor to another, though it is difficult to know how old the various traditions of Jewish chant that exist today actually are. The cantor assists the rabbi by chanting many of the prayers, often in a highly decorative melodic style, and sometimes in unison, harmony or responsorially with the congregation.

The biggest issue in the Diaspora was communal survival. Many Jews came under great pressure to convert to the dominant religion in many of the lands where they found themselves, and some did, but there were always others who refused to do so, no matter how great the threat to their life and liberty. And whereas the Romans did not really mind how the Jews worshiped, as long as they didn't rebel, when the Roman Empire became Christian, things got much worse for the Jews. Christians follow a Jewish man named Yeshua ha-Notzri (Joshua, now known as Jesus, of Nazareth), but they believed that their New Testament made them the real Jews, and those who continued to follow the traditional Jewish laws were to be considered heretics. (Nowadays, Christian replacement theology is much less popular, but for most of the last 2,000 years, it was a commonplace Christian belief.) Unlike the way they treated pagans, Christians did not necessarily try to wipe the Jews out completely, but instead, let them live in often miserable conditions as an object lesson of what happens to heretics.

But this was a checkered existence, and there have been times when Jews have had more or less good lives under Christian protection, too. One of those times was during the empire of Charlemagne (740s-814), who invited Jews to settle in the Rhineland. This area was called Ashkenaz in Hebrew, and therefore, the descendants of this community, who through later expulsions and migrations eventually made their homes throughout most of Europe, are known as Ashkenazim.

Another community of Diaspora Jews settled in Iberia, and whereas Spain is called Sefarad in Hebrew, the descendants of these Jews are known as Sephardim. The Sephardic Jewish community was treated so brutally by the Spanish Christians that they were delighted to help the Muslims conquer Spain in the 8th century. There are some glorious remnants of that time that can be visited, including the Sinagoga de Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo, which was a synagogue, then a convent, armory, warehouse, and now a museum. As a result of the Sephardic Jews' aid to the Muslims in their conquest of Iberia, their descendants were punished with a vengeance when the Christians finally reconquered Spain in 1492. The Spanish Jews in 1492 and the Portuguese Jews in 1496 were given three choices: To convert to Christianity, be burnt at the stake, or leave with their belongings, minus gold, silver and money. Many chose to leave and were given refuge in Muslim lands like Turkey and Morocco, and also in Christian lands including Italy; others converted. The conversos, as they were called, were under constant suspicion, and many of them were arrested by the Inquisition and executed in the succeeding centuries. Toledo became one of the main centers of Inquisition activity.

Another major persecution of the Jews was associated with the Crusaders. During the First Crusade (1096–1099), hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Rhineland were massacred, before the knights sailed for Jerusalem and massacred more Jews, Muslims, and even local Christians. When Saladin defeated the last Crusaders in 1187, the remaining Jews in Israel welcomed him as a liberating hero, as did many of the non-Catholic Christians and Muslims.

Jewish existence in Muslim lands, though better overall than in Christian lands, was also checkered. Jews contributed greatly to the advanced Islamic civilization of the Golden Age (8th-13th centuries) while also advancing the study of their own religion. Probably the most famous authority on the Jewish religion and Jewish thought during that period was Moshe ben Maimon, also called Maimonides (c. 1135-1204), who in addition to being a great rabbi and leader of the Jewish community in Egypt, was also a philosopher and an extremely famous medical authority who spent the last years of his life as the personal physician of Saladin and his family. Jews' position in Muslim lands was based on their status as ahl al-dhimmah (singular: dhimmi), meaning "protected people". Depending on the interpretation of the ruler and his degree of control over subjects who at times resented the non-Muslims in their midst, this could be a very good status or a miserable and dangerous one, and some Muslim rulers, such as the Almohads in 12th-century Spain, even removed this status altogether, thereby denying any protection to non-Muslims in their realm. By contrast, courts in cities in Central Asia such as Bukhara and Samarkand, where Sufi saints and their followers spread a message of love and acceptance, were hospitable to Jews for hundreds of years and employed only Jews as court musicians. You can still hear classical Bukharin music today, anywhere where there are communities of Bukharin Jews, such as in Israel and New York City.

Chasidism and Haskalah

Chasidism is a mystical Jewish movement that was founded in the first half of the 18th century by a man from the Ukraine who is generally acknowledged to have been a great and inspirational rabbi. He is usually known by his nickname, Baal Shem Tov, "Master of the Good Name". Though Baal Shem Tov was a great Torah scholar and is often quoted as such, he was inspired to create a new style of Jewish practice that while continuing to encourage Torah study, also emphasized a joyful connection with God in the forms, for example, of communal singing and dancing. While it's generally the case that all branches of Judaism revere Baal Shem Tov, his closest followers became known as the Chasidim, and they eventually divided into different sects, named after the village or town where their first rebbe or rabbinical spiritual leader came from. So, for example, the Satmarers originated from Satu Mare, Romania, while the Lubavitchers originated from Lyubavichi, Belarus and the Breslovers came from Bratslav, Ukraine. In Israel, the Chasidim are called Haredim or "Ultra-Orthodox" Jews, and some of them are non-Zionist and devote themselves to Torah study, rather than military service. The most famous of the various centers of Haredi Judaism in Israel is in the Mea Shearim neighborhood of Jerusalem. There are also large Chasidic communities in the United States, including Borough Park, Williamsburg and the northern part of Crown Heights in Brooklyn, New York, and the Lubavitchers, also called Chabad, do a lot of "outreach" to other Jews, to encourage them to become more observant of mitzvot (commandments); therefore, there are Chabadniks (Lubavitcher Chasidim) in almost every part of the world where Jews live or visit, helping to enable them to observe the Sabbath and other Jewish holidays. Today, many Chasidim make pilgrimages to the graves of great figures in their sects, such as the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov in Uman, Ukraine and the grave of Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, the last Lubavitcher Rebbe, in Queens, New York. You may recognize Chasidic men by their tradition of dressing in suits and black hats at all times of year.

The Haskalah was the Jewish response to the Enlightenment in Christian countries, and it is generally called the "Jewish Enlightenment" in English. It started in the second half of the 18th century in Galicia (not the Spanish region: this region was then part of Poland and is now divided between Poland and Ukraine; its capital was Lviv) and gained steam in the 19th century, especially in Germany and other German-speaking parts of Central Europe. The Haskalah was a flowering of Jewish secular culture, at first in Yiddish and German, and it spread to other parts of Continental Europe and to the United States and other English-speaking lands. Maskilim, as followers of Haskalah were called, often saw themselves as citizens of their country first and Jews second, but Zionism (see below) was also an outgrowth of Haskalah. So was the new Reform denomination of Judaism, which originated in 19th-century Germany and can be said to have elevated what they considered to be logical thinking over traditional conceptions of Jewish law, with appeals to the example of Maimonides, who applied his own brand of reason in his commentaries on Judaism in his own day.

The worst persecutions and the rise of Zionism

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were numerous pogroms in Czarist Russia, Romania, Poland (especially the section occupied by Russia) and other Eastern European lands. To escape this brutality and to search for opportunity, there was a modern exodus of Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe to the United States, Canada, South Africa, Australia, Latin American countries including Argentina and also parts of Western Europe like Germany, France and the United Kingdom. In this same period, the French Jewish Captain Dreyfus was convicted of trumped-up charges of treason and sentenced to life in a penal colony in French Guiana. He was imprisoned from 1894 to 1906, when he was finally exonerated and released. As horrified as Jews in Western and Central Europe were by the pogroms in Eastern Europe, many of them were even more alarmed at the display of rank Antisemitism in France, a country they considered civilized. As a result, Theodore Herzl (a secular assimilated Jew) and a few like-minded Jews started the Zionist movement, aimed at obtaining land to create a new Jewish state after almost 1900 years of Diaspora.

At first, Zionism was very much a fringe ideology, with only a few chalutzim (pioneers) migrating to Israel with the permission of the Ottoman authorities. As late as the 1930s, the most popular Jewish party was the anti-Zionist Yiddishist Socialist Bund, which sought to promote Yiddish culture along with a united international workers' and peasants' movement. It was only the Shoah, also called the Nazi Holocaust, that brought Zionism front and center, as the Nazi Germans and many of their allies, considering Jews racially subhuman, attempted to wipe out the entire people and murdered about 6 million of them, along with many millions of other people they considered undesirable. (See Holocaust remembrance for a guide to some of the Nazi extermination, transit and slave labor camps and memorials on their sites.) Not only the actions of the Nazis and their allies but the virtual lack of aid by the Allies, who barred all but a few Jewish refugees from their doors and also from Palestine and refused urgent pleas from the Polish Government-in-Exile to assist in actions like a planned rebellion at the Nazi slave labor and extermination camp in Auschwitz, persuaded millions of surviving Jews that their own state was necessary.

Most of the Arabs who lived in the territory the United Nations reserved for the State of Israel were not ready to accept this, and when Israel defeated several Arab armies in its 1947-49 War of Independence, displacing hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs in the process, the situation of Jews living in Arab countries got increasingly oppressive and dangerous. Hundreds of thousands of Jews fled or were forced out of Muslim countries, with most of them going to Israel, France or the United States, and by the 1960s, very few Jews remained in Arab lands where their ancestors had lived for centuries. Vestiges of these communities continue to survive in Iran, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia, but have been virtually wiped out in the rest of the Middle Eastern Muslim lands.

Today, the largest Jewish communities are in Israel, the United States, France, Canada, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Russia, Germany, Brazil, Australia, and by some measures, Ukraine. The largely secular Jews in the former Soviet Union started emigrating in large numbers in the 1970s, with the pace increasing after the fall of communism in the 1990s. Their arrival has changed Israeli politics as well as the face of many Jewish congregations in countries such as Germany. While secular Judaism has a long tradition, the almost total disconnection of many ex-Soviet Jews from Jewish religious culture and heritage proved difficult, and special classes teaching Judaism to Soviet Jews were set up, to better integrate the newly arrived.

Calendar

The Jewish calendar is lunar, so the dates of all holidays shift fairly widely in relation to the solar calendar that is standard in most parts of the world today. The number of the calendar year is supposedly calculated from the time of the Earth's creation. For example, 1 April 2015 is 12 Nisan 5775 in the Jewish calendar, meaning that the World has supposedly existed for only 5775 years. The first day of the Jewish year is called Rosh ha-Shanah.

Holidays

Rosh ha-Shanah and the fast day of Yom Kippur nine days later are called the High Holy Days, when even many otherwise unobservant Jews return to synagogues to pray with the community.

The other most widely celebrated Jewish holidays are Passover, the spring festival when the story of the Exodus from Egypt is retold and celebrated and the foremost family holiday of the Jewish year, and Purim, when the Megillat Esther - the Book of Esther from the Bible - is read, and the victory of the Jews over a man who sought to wipe them out in ancient Persia is celebrated. It is traditional to give gifts on Purim and sometimes Passover; Chanukah, which used to be considered a minor holiday because the books of Maccabees, unlike the books of the Bible that mention the High Holy Days, Passover, Purim and many other holidays, are considered apocrypha (not part of the Tanakh or Jewish Bible), has gained in importance in Christian-majority countries because this festival of lights occurs close to Christmas day, and it is another holiday when gifts may be given. Some other major holidays include Succot, a fall harvest festival when Jews eat meals in temporary booths with greenery like palm fronds on the roof and more leaves on the sides in order to remember the temporary dwellings their ancestors are said to have lived in during the Exodus; the following holiday of Simchat Torah, literally "Happiness of the Torah", when the yearly cycle of Torah readings ends and Torah scrolls are carried through the synagogue and frequently out onto the street, where joyous congregants dance with them; and Shavuot, a late spring harvest festival that also celebrates God's gift of the Torah at Mount Sinai and is traditionally marked by all-night Torah study. The most frequent Jewish holiday of them all is Shabbat, the Sabbath, which occurs every week from 18 minutes before sunset Friday to whenever three stars are visible in the Saturday night sky. During this period, any form of work (very broadly defined) is strictly forbidden. It is common for observant Jews to go to the synagogue to pray every Saturday morning, but Friday night prayers and the closing Havdalah prayers on Saturday night are frequently done at home with the family and any relatives or friends who have come to visit.

Cities

- See also: Holy Land

Israel/Palestine

- Jerusalem, the holy city, former location of the Temple and current location of the Western Wall

- Hebron - a city with a long Jewish tradition, only broken shortly due to a massacre against the Jewish population in 1929 and the driving out of the Jews in the territory conquered by Jordan in 1948. The city was conquered by Israeli forces in 1967 and a small Jewish community lives in it again

- Tiberias

- Safed

- Bethlehem city of King David

Diaspora

Germany

- Berlin/Mitte — the beautiful Neue Synagoge survived Nazism due to the insistence of a policeman on protecting the building on Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass in 1938, when the Nazis destroyed numerous synagogues and Jewish businesses and brutalized Jewish communities throughout Germany and Austria). Elsewhere in Mitte, there is a moving Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe

- Dresden - the original synagogue (built to plans by Gottfired Semper, the architect of the eponymous opera) was destroyed by the Nazis and the "replacement" built in the early 2000s looks emphatically "not like a synagogue" and was decried as something of an eyesore initially. However, this was deliberate at least in part, as the new synagogue is intended not only to show the resurgence of Jewish live, but also that there was a break in Jewish tradition and what caused it. Unusual for a synagogue in Germany, there is no metal scanner or other visible safety measures and frequent guided tours are in keeping with this "open" approach.

Greece

- Thessaloniki — known as "the mother of Israel" due to its once large Jewish population (for centuries when it was under the Ottoman rule, Thessaloniki was the only city in the world which had a Jewish-majority population), the city lost most of its historic Jewish quarters during the Great Fire of 1917 and the Holocaust that followed later. However, a Jewish museum and two synagogues still exist.

Hungary

- Budapest/Central Pest — Central Pest contains the Jewish Quarter of Budapest; the Jewish community, though it was reduced in number by the Nazis and their collaborators and by immigration, is still substantial, with kosher eateries and shops and various synagogues, including the Great Synagogue on Dohány Street, which in recent decades was renovated with contributions by the late American actor, Tony Curtis, the son of two Hungarian Jewish immigrants. On the second floor of the same building, with a separate entrance, is a Jewish Museum that displays many beautiful antique Jewish ritual objects

Italy

- Florence — like other Italian cities, its Jewish population was much reduced after the Nazis occupied the country in 1943, but its attractive synagogue is still active and along with the Jewish Museum in the same building, it is a secondary attraction in this city of incredible attractions

- Rome — the Jewish Quarter of Rome, which housed the city's ghetto starting in the mid 16th century, is often visited nowadays; Roman cuisine was also influenced by its Jewish community as, for example, Carciofi alla giudìa (Jewish-style artichokes) is a local specialty

- Venice — this city gave the world the word Ghetto, used to describe a neighborhood to which Jews were restricted; the Venice Ghetto still exists and is still the center of Jewish life in the city, though the Jewish community is now quite small and its members have the same rights as all other Italian citizens

Suriname

- Jodensavanne — Dutch for the "Jewish Savanna," this was a thriving agricultural community in the midst of the Surinamese Rainforest founded by the Sephardic Jews in 1650. It was abandoned after a big fire caused by a slave revolt in the 19th century. Its ruins, including that of a synagogue, are open for visits.

Tunisia

- Djerba — the El Ghriba Synagogue, which has a beautiful interior, is a historic place of pilgrimage for Tunisia's Jewish community.

Turkey

- Edirne — once among the cities with the largest populations of Ottoman Jews, Edirne's Grand Synagogue, the third largest in Europe, was restored to a brand new look in 2015 after decades of dereliction.

- Istanbul's Karaköy district, arguably deriving its name from Karay — the Turkish name for the Karaites, a sect with its own purely Biblical, non-rabbinic interpretation of Judaism — has a couple active synagogues as well as a Jewish museum. Balat and Hasköy on the opposite banks of the Golden Horn facing each other were the city's traditional Jewish residential quarters (the latter also being the main Karaite district), while on the Asian Side of the city, Kuzguncuk is associated with centuries old Jewish settlement.

- Izmir — the ancient port city of Smyrna had a significant Jewish presence (and it still has to a much smaller degree). While parts of the city, especially the Jewish quarter of Karataş, have much Jewish heritage (including an active synagogue and the famed historic elevator building), their most celebrated contribution to the local culture is boyoz, a fatty and delicious pastry that is brought by the Sephardic expellees from Iberia as bollos and is often sold as a snack on the streets, in which the locals like to take pride as a delicacy unique to their city.

- Sardis — an archaeological site with the ruins of a Roman era synagogue, one of the oldest in diaspora. The native Lydian name for this ancient city was Sfard, which some think is the actual location of Biblical Sepharad (identified by the later Jews with Iberia).

Ukraine

- Uman, where the grave of the Breslover Rebbe, head of the Breslover Chasidim, is buried

Respect

When entering any Jewish place of worship, all males over 13 are normally expected to wear a hat, such as a skullcap (called a kipah in Hebrew and a yarmulke in Yiddish). If you have not brought a hat with you, there is normally a supply available for borrowing, for example outside the sanctuary in a synagogue. Both men and women can show respect by dressing conservatively when visiting synagogues or Jewish cemeteries, for example by wearing garments that cover the legs down to at least the knees, and the shoulders and upper arms. Orthodox Jewish women wear loose-fitting clothing that does not display their figure, and many cover their hair with a kerchief or wig while in synagogues or other holy places.

Talk

Hebrew and Aramaic are the ancient holy languages of Judaism, and are used for worship in synagogues throughout the world. The two languages are closely related and used the same alphabet, so anyone who can read Hebrew will have little trouble with Aramaic.

Modern Hebrew, revived as part of the Zionist movement starting in the late 19th century, is the official and most spoken language in Israel. Other languages often spoken by Jews are the languages of the country they reside in or used to live in before making Aliyah (particularly English, Russian, Spanish, French, Arabic and German) as well as Yiddish, which developed from Middle High German with borrowed words from Hebrew, Slavic languages and French, but is written in Hebrew letters rather than the Latin alphabet. Many languages have been written in Hebrew letters in historic times. Before the Nazi Holocaust, Yiddish was the first language of over 10 million people; now, it is mostly spoken by Chasidim. Ladino, similarly, was Judeo-Spanish, and used to be widely spoken among Sephardic Jews living in Turkey and other Muslim countries that had given them refuge. While Yiddish is still very much alive in both Israel and parts of the US and several Yiddish loanwords have entered languages such as (American) English and German, Ladino is moribund and only spoken by a few elderly people and hardly any children or adolescents.

See

- Synagogues, especially those built in the 19th century in Europe when Jews were getting the normal civil rights their non-Jewish peers had enjoyed in their countries for centuries are often architecturally spectacular and most of them are willing and able to give tours. Sadly many synagogues (especially in Germany) were destroyed by the Nazis, and if they were rebuilt at all, some of them show a somber reflection about the destruction of Jewish life in the past. Others, however were rebuilt very much in the original style and are truly a sight to behold. Unfortunately, synagogues and Jewish museums are a target for all kinds of Antisemitic violence and thus heightened security measures are often taken, so allow extra time just as you do when going to the airport.

- Museums of Judaism and/or Jewish history exist in many places and are often full of beautifully decorated Jewish religious books and ritual objects, as well as historical information.

Do

- Attend a service — If you are interested in experiencing the practice of Judaism, not only Jews but non-Jews are welcome at many synagogues. Many synagogues have services every day, but particularly on Friday nights and Saturday mornings for Shabbat, the Sabbath, whose observance is one of the Ten Commandments. If you would like to listen to brilliant cantillation (chanting), ask around to find out which local synagogues have the most musical cantors. And if there's no synagogue, Chabad, also called the Lubavitcher Chasidim, has many far-flung outposts around the world, and if you are Jewish or travelling with a Jew, they are happy to invite you to a service at their house or a meeting room.

- Go to an event at a Jewish center — There are Jewish centers in many places where there are classes, lectures, performances, film showings and art exhibitions. Most of them have online calendars.

- Charity — Tzedakah is the Hebrew word for "charity", and it is a central mitzvah (commandment) of the Jewish religion. Jews tend to give generously to charity, and there are many Jewish charities, some of which specifically focus on helping other Jews in need, but many of which serve the poor of all creeds. If you would like to be charitable, seek out a Jewish or non-sectarian organization or one run by members of whichever religion you adhere to that focuses on a cause you believe in, or just take out the time to personally help someone who could use a hand.

Buy

If you are interested in buying Jewish ritual objects and other things Jewish, look for Judaica stores. Popular items to buy include Shabbat candlesticks; menorahs (9-branched candelabras for Chanukah); jewelry with traditional motifs including the Hebrew letters chet and yod for chai, the Hebrew word for "life", and a silver hand, representing the hand of God; Torahs, prayer books, and books of commentary; mezuzot (miniature scrolls of parchment inscribed with the words of the Shma Yisrael prayer, beginning with the words "Hear O Israel! The Lord is our God; the Lord is One!" in decorative cases, to be used as doorposts); and Jewish cookbooks.

Eat

Under traditional Jewish dietary laws, only kosher food may be eaten by Jews; see Kashrut. As Jewish law forbids starting a fire on the Sabbath, a special Sabbath cuisine has developed that deals with this issue and often produces "slow-cooked" meat and vegetables.

Drink

Wine is used sacramentally on the Sabbath (Shabbat) and other Jewish holidays. Some of it is highly fortified with sugar, but nowadays, much excellent kosher wine is produced in Israel, the United States, France, Italy, Spain, and various other countries. Wine for Passover must be Kosher l'Pesach, so if you are invited to a seder (a festive Passover meal), look for that special designation when purchasing wine for your hosts.

Most Jews consider alcoholic drinks other than wine to be per se kosher, with only a few obvious exceptions (e.g., mezcal con gusano, as grubs are treif). However, drunkenness is at the very least strongly frowned on, except on two holidays: Passover, when according to some interpretations of law, every adult should drink 5 full cups of wine (though in practice, grape juice is commonly considered OK to substitute) and Purim, when there's a tradition that you should drink so much wine that you can't tell Mordecai (the hero of the holiday) from Haman (the villain).

Sleep

Any Orthodox (or "Shomer Shabbos" — that is, guarding the Sabbath) Jew cannot violate the Jewish law against traveling on Friday nights and Saturdays, which also applies to most Jewish holidays. Therefore, s/he must arrange to sleep somewhere close enough to walk to a synagogue on those days, or in the case of communal holidays that take place in homes (for example, Kabbalat Shabbat to welcome in the Sabbath on Friday night, the Seder on Passover, or the reading of the Megillas Esther [Biblical Book of Esther] on Purim), to the place where the ceremony and festive meal are taking place. It is therefore traditional for Orthodox Jews to open their homes to other observant Jews visiting from far away. If you are a Sabbath-observant Jew and don't know anyone in a place where you are traveling during a Sabbath or holiday, you can usually contact the local Chabad office for advice, as long as you call them before the holiday starts, or you could also try calling a local synagogue.