Leicester Cathedral

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2012) |

| Leicester Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of Saint Martin | |

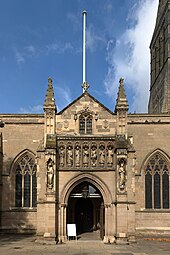

Leicester Cathedral from the south | |

| 52°38′05″N 1°08′14″W / 52.634644°N 1.137086°W | |

| Location | Leicester, Leicestershire |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | leicestercathedral |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built | 1086–1867 |

| Specifications | |

| Number of spires | 1 |

| Spire height | 67.1 metres (220 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Leicester (since 1927) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Martyn Snow |

| Dean | Karen Rooms |

| Precentor | Emma Davies |

| Canon(s) | 1 diocesan vacancy |

| Canon Pastor | Alison Adams |

| Canon Missioner | vacant |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Christopher Johns |

| Organist(s) | David Cowen, Rosie Vinter |

The Cathedral Church of Saint Martin, Leicester,[1] commonly known as Leicester Cathedral,[2] is a Church of England cathedral in Leicester, England and the seat of the Bishop of Leicester.[3] The church was elevated to a collegiate church in 1922 and made a cathedral in 1927 following the establishment of a new Diocese of Leicester in 1926.[4][5][6]

The remains of King Richard III were reburied in the cathedral in 2015 after being discovered nearby in the foundations of the lost Greyfriars chapel, 530 years after his death.[7][8]

History[edit]

Leicester Cathedral is near the centre of Leicester's medieval Old Town. The Cathedral famously houses King Richard III's tomb.

The church was built on the site of Roman ruins[9] and is dedicated to St Martin of Tours, a 4th-century Roman officer who became a Bishop. It is almost certainly one of six churches referred to in the Domesday Book (1086) and portions of the current building can be traced to a 12th-century Norman church which was rebuilt in the 13th and 15th centuries. In the Middle Ages, its site next to Leicester's Guild Hall, ensured that St Martin's became Leicester's Civic Church with strong ties to the merchants and guilds of the town.

Much of the extant building is predominantly Victorian. This included the building of the tower (completed in 1862) and 220-foot spire (1867) by the architect Raphael Brandon. The work on this was in the correct Early English style, although his work elsewhere in the church was in the perpendicular style. The tower and spire are, according to Pevsner, "intentionally impressive" and loosely based on the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Ketton in Rutland.[10]

In 1927, St Martin's was dedicated as Leicester's Cathedral when the diocese was re-created, over 1,000 years after the last Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Leicester fled from the invading Danes.

Today over one hundred thousand people visit Leicester Cathedral every year, primarily to see the tomb of King Richard III, the last English monarch to die in battle. King Richard's mortal remains were interred by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in March 2015 after five days of commemoration events and activities around the city and county of Leicester. A magnificent tomb cut of a single piece of Swaledale fossil stone weighing 3 tonnes now covers his grave.

Inside, on permanent exhibition, is the Pall, a decorative cloth which covered King Richard's coffin during his reinterment. It was designed and created by artist Jacquie Binns. The embroidery tells the story of King Richard's life and the discovery of his body in a car park very near to the cathedral. Other items that can be seen inside the Cathedral include 14th-century wooden carved figures, each “afflicted” with some kind of illness. One has a medieval hearing aid, while another is suffering from sore shoulders.

A church dedicated to St Martin has been on the site for about 900 years, being first recorded in 1086 when the older Anglo-Saxon church was replaced by a Norman one.[4][6] The present building dates to about that age, with the addition of a spire and various restorations throughout the years.[6][11] Most of what can be seen today is a Victorian restoration by architect Raphael Brandon.[11] The cathedral of the former Anglo-Saxon diocese of Leicester was on a different site.

A cenotaph memorial stone to Richard III was until recently located in the chancel; it was replaced by the tomb of the King himself. The monarch, killed in 1485 at the Leicestershire battlefield of Bosworth Field, had been roughly interred in the Greyfriars, Leicester. His remains were exhumed from the Greyfriars site in 2012, and publicly confirmed as his following DNA testing in February 2013.[7][8] Peter Soulsby, Mayor of Leicester, and David Monteith, the cathedral's canon chancellor, announced the King's body would be re-interred in Leicester Cathedral in 2015. This was carried out on 26 March.

The East Window was installed as a monument to those who died in World War I. The highest window contains a sun-like orb with cherubs radiating away from it. In the centre Jesus sits holding a starry heaven in one hand with one foot on a bloody hell. Surrounding Jesus are eight angels whose wings are made from a red glass. To the far right stands St Michael the Archangel, who stands on the tail of a dragon. The dragon goes behind Jesus and can be seen re-emerging under the feet of St George who stands on its head. On the bottom row can be seen from left St Joan of Arc, Mary, Jesus with crying angels, Mary Magdalene, James, and St Martin of Tours. The window includes an image of a World War I soldier.

The tower and spire were restored both internally and externally in 2004–5. The main work was to clean and replace any weak stonework with replacement stone quarried from the Tyne Valley. The cost was up to £600,000, with £200,000 being donated by the English Heritage, and the rest raised through public donations.[12]

The cathedral has close links with Leicester Grammar School which used to be located directly next to it. Morning assemblies would take place each week on different days depending on the school's year groups, and services were attended by its pupils. The relationship continues despite the school's move to Great Glen, about seven miles south of Leicester.[13][14]

In 2011, after extensive refurbishment, the cathedral's offices moved to the former site of Leicester Grammar School, and the building was renamed St Martin's House. The choir song school also relocated to the new building, and the new site also offers conference rooms and other facilities that can be hired out. The new building was officially opened by the Bishop of Leicester in 2011.[15]

In July 2014, the cathedral completed a redesign of its gardens, including installation of the 1980 statue of Richard III.[16] Following a judicial review decision in favour of Leicester, plans were made to reinter Richard III's remains in Leicester Cathedral, including a new tomb and a wider reordering of the cathedral interior. Reinterment took place on 26 March 2015 in the presence of Sophie, Countess of Wessex (representing Queen Elizabeth II) and Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester.[17]

On 13 April 2017, Queen Elizabeth II distributed Maundy money in the cathedral to 182 recipients.[18]

In 2022, archaeological excavations began, led by the University of Leicester team which discovered the remains of Richard III, of a burial ground going back to the late Anglo-Saxon period on the site of the Old Song School as part of the Leicester Cathedral Revealed project to build a new heritage and educational centre.[19]

In March 2023, a 1,800 year-old Roman era stone altar was discovered in the grounds of the cathedral by the University of Leicester.[20]

Architecture[edit]

Leicester Cathedral is a Grade II* listed building comprising a large nave and chancel with two chancel chapels, along with a 220-foot-tall spire which was added in 1862. The building has undergone various restoration projects over the centuries, including work by the Victorian architect Raphael Brandon, and the building appears largely Gothic in style today. Inside the cathedral, the large wooden screen separating the nave from the chancel was designed by Charles Nicholson and carved by Bowman of Stamford.[21][22] In 2015 the screen was moved eastward to stand in front of the tomb of Richard III, as part of the reordering of the chancel by van Heyningen and Haward Architects.[23]

Vaughan Porch[edit]

The Vaughan Porch which is situated at the south side of the church was designed by J. L. Pearson, who was also the architect of Truro Cathedral. It is named the Vaughan Porch because it was erected in memory of the Vaughans who served successively as vicars throughout a great part of the nineteenth century. The front of the porch depicts seven saintly figures set in sandstone niches, all of whom are listed below.[24]

- Guthlac c 673–713 was a Christian saint from Lincolnshire who lived when Leicester was first made a diocese in the year 680

- Hugh of Lincoln c 1135–1200 was a French monk who founded a Carthusian monastery and worked on the rebuilding of Lincoln Cathedral after an earthquake destroyed it in 1185. In Norman times Leicester was situated within the Diocese of Lincoln.

- Robert Grosseteste c 1175–1253 was an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He is also the most famous of the medieval Archdeacons of Leicester.

- John Wycliffe c 1329–1384 was an Oxford scholar and is famous for encouraging two of his followers to translate the Bible into English. Foxe's famous "Book of Martyrs" (which commemorates the Protestant heroes of the reformation era) begins with John Wycliffe.

- Henry Hastings c 1535–1595 was the 3rd Earl of Huntingdon. The Leicester home of the Earls of Huntingdon was in Lord's Place off the High Street in Leicester, and Mary, Queen of Scots stayed there as a prisoner on her journey to Coventry.

- William Chillingworth 1602–1643 was an Oxford theologian, a friend of Jeremy Taylor and nephew of Archbishop Laud. He was Master of Wyggeston Hospital and became a Chaplain to the Royalist army in the Civil War.

- William Connor Magee 1821–1891 was Bishop of Peterborough and encouraged the building of many of Leicester's famous Victorian churches and a large number of parochial schools. He appointed the first suffragan Bishop of Leicester, Francis Thichnesse, in 1888. Magee later became Archbishop of York.

Chapels[edit]

The cathedral contains four separate chapels, three of which are dedicated to a different saint. St Katharine's and St Dunstan's Chapels act as side chapels and are used occasionally for smaller services and vigils. St George's Chapel, which is located at the back (or west) of the cathedral commemorates the armed services, and contains memorials to those from Leicestershire who have been killed in past conflicts. The new Chapel of Christ the King adjoins the East Window.

St Katharine's Chapel is located on the north side of the cathedral to the left of the sanctuary. In the window above the altar is St Katharine, who was tied to a wheel and tortured (hence the firework named after her). Below this is a carved panel showing Jesus on the cross with Mary and John on either side of him. St Francis of Assisi and the 17th-century poet Robert Herrick are also pictured – indeed, the chapel is sometimes referred to as the "Herrick Chapel".

St Dunstan's Chapel, located on the other side of the chancel to St Katharine's Chapel, is specially put aside for people to pray in. A candle burns in a hanging lamp to show that the sacrament of Christ's body and blood is kept here to take to those who are too ill to come to church. The walls of the chapel are covered with memorials to people who have prayed in the chapel. St Dunstan was Archbishop of Canterbury in the 10th century, and scenes from his life are depicted in the south-east window.

St George's Chapel was the chapel of the Guild of St George. The effigy of England's national saint, on a horse, was kept here and borne through the streets annually on 23 April in a procession known as "riding the George".[citation needed] The legend of George killing a dragon is shown in one of the chapel's windows. The chapel, enclosed by a carved wooden screen, was reconstructed in 1921 and contains memorials to the men of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Here the battle honours of the Regiment and the names of those killed in the Crimean, South African and two World Wars are recorded and remembered.[25]

The new Chapel of Christ the King was created at the east end of the cathedral as part of the re-ordering work for the burial of Richard III.[23]

Services[edit]

Leicester Cathedral follows the rites of the Church of England and uses Common Worship for the main Choral Eucharist on Sunday.[26]

Cathedral staff[edit]

Provosts and deans[edit]

- 1927–1934 Frederick MacNutt (was the first provost of Leicester Cathedral, and also acted as Archdeacon of Leicester, 1921–1938, and was subsequently a Canon at Canterbury Cathedral, 1938–1948)

- 1938–1954 Herbert Jones (subsequently Dean of Manchester, 1954–1963)

- 1954–1958 Mervyn Armstrong (subsequently Bishop of Jarrow, 1958–1965)

- 1958–1963 Richard Mayston

- 1963–1978 John Hughes

- 1978–1992 Alan Warren

- 1992–1999 Derek Hole

- The title of Provost was changed in 2002 to Dean.[27]

- 2000–2012 Viv Faull (was the first Dean of Leicester Cathedral after the post was renamed in 2002. She was also the first female dean to be appointed in the Church of England.[28] She became Dean of York Minster in September 2012).[29]

- 2013–2022 David Monteith[30]

Dean and chapter[edit]

As of 17 December 2022:[31]

- Dean – Karen Rooms (since 9 March 2024 installation)[32]

- Canon Pastor (SSM) – Alison Adams (a canon, and Diocese and Cathedral Social Responsibility Enabler, since Pentecost Sunday, 19 May 2013, installation;[33] Pastor since February 2016;[34] Sub-Dean February 2016–summer 2022;[35] Acting Dean, 17 October 2016 – 31 January 2017)[36]

- Canon Precentor – Emma Davies (installed 31 January 2021; Acting since 1 July 2019)[37]

- Cathedral canonry – vacant since Rooms' 9 March 2024 resignation as Sub-Dean, Canon Missioner and City Centre Priest-in-Charge (at St Nicholas)

- Diocesan canonry – vacant since 22 January 2022 resignation;[38] previously Chancellor and Diocesan Director of Ordinands

- Other clergy:

Lay staff[edit]

- Director of Music – Christopher Ouvry-Johns

- Assistant Director of Music and Head of Music Outreach – Rosie Vinter

- Associate Organist – David Cowen

- Head Verger – Beverley Collett

- Head Server – Neill Addison

Choir[edit]

The Leicester Cathedral Choir is made up of the Boys Choir, the Girls Choir and the Cathedral Songmen. Boys and girls are recruited from schools throughout Leicester and Leicestershire, whilst many of the songmen originally joined the choir as trebles and have stayed on after their voice broke. The cathedral also offers scholarships worth around £1000 a year to gap year and university students at Leicester University and De Montfort University.[39] Whilst the choir occasionally produces CDs and other recordings, it is also one of the few cathedral choirs apparently never to have appeared on BBC Radio 3's Choral Evensong although it broadcast Choral Evensong several times in the days when the programme used to go out on the BBC Home Service. As part of the preparations for the reburial of Richard III at Leicester Cathedral, British furniture designers Luke Hughes designed new choir and clergy furniture[40] from solid oak for a new choral layout within the nave.

The choir participates in regular festivals, with the annual RSCM Leicestershire festival in September often taking place in the cathedral itself. Each year during February the choir joins those of Derby and Coventry cathedrals and, more recently, Southwell Minster for what is known as the Midlands Four Choirs Festival. Hosting duties rotate among the four cathedrals, although the repertoire is chosen, and music conducted, by the directors of music of all participating choirs.

Choir tours[edit]

The cathedral choir tours abroad typically once every three to four years, and in both 1998 and 2005 they visited Japan. Other destinations abroad have included Rhode Island in the United States, Germany, and France. In other years, the choir has spent a week during the summer in residence at another English cathedral church, such as Lincoln, Wells, York and Chester.[41][42] The boys and girls choirs, as well as the younger songmen also spend five days in August at Launde Abbey, a retreat house in east Leicestershire.[43]

Organ and organists[edit]

Organ[edit]

The present organ was installed by J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd in 1873 and since then has been rebuilt by Harrison and Harrison in 1929 and 1972. A specification of the organ can be found on the National Pipe Organ Register.[44]

Organists and directors of music[edit]

- Richard Hobbs to 1753[45] (afterwards organist of St Martin in the Bull Ring, Birmingham)

- William Boulton to 1765[46]

- Anthony Greatorex 1765 – c. 1772 (father of Thomas Greatorex, who became organist at Westminster Abbey)[46]

- Martha Greatorex 1772–1800 (daughter of Anthony Greatorex)[46]

- Sarah Valentine 1800–1843 (sister of Ann Valentine, who was organist at St Margaret's Church, Leicester)[47]

- John Morland 1870–1875

- Charles Hancock 1875–1927

- Gordon Archbold Slater 1927–1931 (subsequently organist at Lincoln Cathedral 1931–1966)

- George Charles Gray 1931–1969 (previously organist at St Michael le Belfrey, York and St Mary-le-Tower, Ipswich

- Peter Gilbert White 1969–1994 (previously Assistant Organist of Chester Cathedral 1960–1962)

- Jonathan Gregory 1994–2010 (previously organist of St Anne's Cathedral, Belfast, now Director of Music of the UK Japan Choir)

- Christopher Ouvry-Johns 2011–present (formerly Choral Director in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Leeds)

Assistant organists and assistant directors of music[edit]

- Frederick William Dickerson

- Dennis Arnold Smith 1918

- Stanley Vann 1932 (subsequently Master of the Music at Peterborough Cathedral 1953–1977)

- Thomas Bates Wilkinson 1933[48]

- Wallace Michael Ross 1951 (subsequently assistant organist at Gloucester Cathedral 1954–1958, and organist of Derby Cathedral 1958–1982)

- Sidney Thomas Rudge 1955

- Robert Prime 1965

- Geoffrey Malcolm Herbert Carter 1973 (subsequently organist of St Mary's Church, Humberstone)

- David Cowen 1995 (now Associate Organist of Leicester Cathedral)

- Simon Headley 1999 (subsequently assistant director of Music – see below)

In 2013, the title of the post was changed to Cathedral Organist and assistant director of Music.

- Simon Headley 2010–2018 (also acted as acting director of Music in the Autumn of 2010 between the departure of Jonathan Gregory and the appointment of current Director of Music, Christopher Ouvry-Johns)

In 2019, the title of the post was changed to assistant director of Music and Head of Music Outreach.

- Rosie Vinter 2019–present

Bells[edit]

The tower of the cathedral has 13 bells (including a peal of 12). These can be heard on Thursday evenings and Sunday mornings, with peals being rung on special days. The tenor bell weighs 25–0–20.[49]

The following is the full list of the inscriptions on the thirteen bells.

- XII THE CORONATION BELL OF HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE VIth RECAST BY THE FREEMASONS OF LEICESTERSHIRE AND RUTLAND 12 May 1937. F B MACNUTT PROVOST C F OLIVER PROVINCIAL GRAND MASTER GOD SAVE THE KING H Watchorn Esq. Mayor J Nichols. W Capp Churchwardens Edwd. Arnold Fecit 1781

- XI THE NORTH BELL RECAST BY ALDERMAN SIR JONATHAN NORTH J.P. MAYOR OF LEICESTER 1914–1918 and WILLIAM ALBERT NORTH J.P. HIGH SHERIFF OF LEICESTERSHIRE 1935–36. 12 May 1937 GOD SAVE CITY AND SHIRES Recast by J Taylor and Co. 1879 Edward Arnold Fecit 1781 Thomas Ingram 1879

- X THE BELL OF THE CONGREGATION RECAST BY THE CONGREGATION OF THE CATHEDRAL 12 May 1937 GOD SAVE HIS CHURCH H Watchorn Esq. Mayor J Nichols. W Capp Churchwardens Edward Arnold Fecit 1781

- IX THE SAMSON SMITH BELL RECAST BY SAMSON SMITH OF LEICESTER 12 May 1937 CHRIST IS RISEN ALLELUYA H Watchorn Esq. Mayor J Nichols. W Capp Churchwardens Edwd. Arnold Fecit 1781

- VIII THEJARVISBELL RECAST BY WILLLAM GEORGE JARVIS CHURCHWARDEN AND DEPUTY WARDEN OF ST MARTINS 12 May 1937 ADESTE. FIDELES. GAUDETE. ORATE. Praise him upon the well tuned cymbals: Praise him upon the loud cymbals. 1781

- VII THE PARTRIDGE BELL RECAST IN MEMORY OF SAMUEL STEADS PARTRIDGE J.P. BY HIS WIFE ELIZABETH PARTRIDGE 12 May 1937 GOD SEND US PEACE IN CHRIST J Taylor & Co. Founders Loughborough MDCCCLXXIX Continentia THE STELFOX BELL (HALF-TONE) GIVEN IN MEMORY OF JAMES WALTER STELFOX, LAY CANON, CHURCHWARDEN AND DEPUTY WARDEN OF ST MARTINS BY HIS WIFE EVELYN MARSLAND STELFOX 12 May 1937 NON CLAMOR SED AMOR

- VI THE DANIELS BELL RECAST BY SAMUEL KILWORTH DANIELS, LAY CANON OF ST MARTINS IN MEMORY OF HIS WIFE CAROLINE DANIELS 12 May 1937 IN HIS WILL IS OUR PEACE

- V THE FIELDING JOHNSON BELL RECAST IN MEMORY OF THOMAS FIELDING JOHNSON MA, J.P. LAY CANON OF ST MARTINS AND HIS WIFE FLORENCE LYNE JOHNSON BY THEIR CHILDREN FLORENCE JULIA FIELDING EVERARD J.P. AGNES MIRIAM FIELDING JOHNSON, WILLIAM SPURRETT FIELDING JOHNSON 12 May 1937 PEACE TO THEM THAT ARE AFAR OFF AND TO THEM THAT ARE NIGH Rev. Edward Thomas Vaughan Vicar, Henry Sharpe Jones. Joseph Simpkin Church Wardens. John Taylor & Son Bellfounders Loughhorough Late of Oxford, Bideford Devon and St. Neots Hunts. Successors to the old and celebrated Founders Newcombe, Watts, Eyre and Arnold of Leicester. Names of high repute dating as early as 1560.

- IV THE GERTRUDE ELLIS BELL RECAST IN MEMORY OF GERTRUDE ELLIS BY HER DAUGHTER FREDA LORRIMER AND HER NIECE KATHLEEN BROWNING 12 May 1937 JOHN TAYLOR AND SON FOUNDER OXFORD AND LOUGHBOROUGH A.D. 1854.

- III THE BOWMAR BELL RECAST IN MEMORY OF WALTER HAMMOND BOWMAR BY HIS WIFE EVA BOWMAR 12 May 1937 JESU CHRISTE MISERERE NOVIS John Taylor & Son Founders Loughborough A.D. 1854.

- II THE JOHN EDWARD ELLIS BELL GIVEN IN MEMORY OF JOHN EDWARD ELLIS LAY CANNON, CHURCHWARDEN AND DEPUTY WARDEN OF ST MARTINS BY HIS WIFE MABEL ELLIS AND HIS DAUGHTER FREDA LORRIMAR AND HIS NIECE KATHLEEN BROWNING 12 May 1937 PRAISE GOD FOR BLESSED MARTIN, SOLDIER BISHOP SAINT

- I THE BELLFOUNDERS BELL GIVEN BY E DENISON TAYLOR BELLFOUNDER LOUGHBOROUGH 12 May 1937

Tomb of Richard III[edit]

In August 2012, Leicester City Council, the University of Leicester, and the Richard III Society, spurred by the work of Philippa Langley, began a search underneath a car park in Leicester, to find King Richard III's remains.

On 26 March 2015, Richard III was reburied in Leicester Cathedral.[51] The last burial of an English monarch prior to this was 43 years earlier, for Edward VIII, who abdicated and became Duke of Windsor, in 1972.

The cathedral tomb was designed by van Heyningen and Haward Architects[52] and made by James Elliott.[53] The tombstone features a cross deeply incised into a rectangular block of pale Swaledale fossil stone quarried in North Yorkshire. It rests on a low plinth of dark Kilkenny limestone which is incised with Richard's name, dates and motto, carved by Gary Breeze and Stuart Buckle; and which carries his coat of arms in pietra dura by Thomas Greenaway.[54][55]

The remains of Richard III are in a lead ossuary inside an English oak coffin crafted by Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard's sister Anne of York. The coffin lies in a brick-lined vault below the floor, under the plinth and tombstone.[55]

See also[edit]

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of ecclesiastical restorations and alterations by J. L. Pearson

References[edit]

- ^ NA, NA (25 December 2015). The Macmillan Guide to the United Kingdom 1978-79. Springer. ISBN 9781349815111.

- ^ "Leicester Cathedral – A beating heart for City and County". Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Welcome to Leicester Cathedral – Leicester Cathedral". Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b "History of Leicester Cathedral – Leicester Cathedral". Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c Express, Britain. "Leicester Cathedral & Richard III Memorial | History & Photos". Britain Express. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b "'Strong evidence' Richard III's body has been found – with a curved spine". The Daily Telegraph. London. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Richard III dig: DNA confirms bones are king's". BBC News. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Roman shrine uncovered beneath graveyard in Leicester Cathedral in England". ABC News. 8 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1984). Williamson, Elizabeth (ed.). Leicestershire and Rutland. Buildings of England (Second Edition reprinted with corrections 1992 ed.). London: Penguin. p. 208. ISBN 0-14-071018-3.

- ^ a b "Leicester Cathedral - Story of Leicester". www.storyofleicester.info. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "£2m package to repair cathedrals". The Guardian. London. 29 January 2004.

- ^ Leicester Grammar School Teamwork — Moral & spiritual well being Archived 3 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leicester Grammar Junior School Who we are

- ^ Neil Binley. "About St Martins House Leicester". stmartinshouse.com.

- ^ Leicester's Richard III statue reinstated at Cathedral Gardens BBC News Leicester, 26 June 2014

- ^ Richard III tomb design unveiled in Leicester BBC News, 16 June 2014

- ^ Bird, Daniel (13 April 2017). "Queen visits Leicester: Her Majesty and Prince Philip attend Maundy Service". Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ Medievalists.net (27 May 2022). "New archaeological work begins at Leicester Cathedral". Medievalists.net. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Excavations reveal Roman altar stone in shrine or cult room". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 7 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ The spire is a Broach spire. Arts in Leicestershire Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Leicester Cathedral". Cathedral Plus. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Richard III Tomb and Burial". Leicester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "The Vaughan Porch". Leicester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Leicester Cathedral Guide". Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Service and Opening Times". Leicester Cathedral. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "City's dean 'honoured' by new role at York Minster". Leicester Mercury. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Diocese of York staff accessed 23 February 2013

- ^ "The Very Rev Vivienne Faull appointed Dean of York Minster". BBC News.

- ^ "New Dean of Leicester announced". anglican.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014.

- ^ Leicester Cathedral — Cathedral Clergy and Pastoral Team (Accessed 8 December 2022)

- ^ "Karen Rooms installed as Dean of Leicester". Leicester Cathedral. 11 March 2024. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "The Very Revd David Monteith installed as Dean". anglican.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Appointments". www.churchtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Adams was Sub-Dean until after 1 May 2022 [1] and Rooms became Sub-Dean before 26 June 2022 [2]

- ^ Leicester Cathedral notice sheet, 2 October 2016 Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "New Canon Missioner, the Revd Paul Rattigan". 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022.

- ^ "University Choral Scholarships". Leicester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Warzynski, Peter. "New seating installed at Leicester Cathedral". Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Leicester Cathedral Tours Archived 5 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BCSD – Leicester Cathedral Choir". boysoloist.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ "Home – Launde Abbey". Launde Abbey.

- ^ "The National Pipe Organ Register – NPOR". npor.org.uk.

- ^ "Birmingham Organists". Birmingham Daily Post. England. 13 April 1939. Retrieved 18 January 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Kroeger, Karl (Summer 2008). "Leicester's Lady Organists, 1770–1800" (PDF). CHOMBEC News (5). Bristol: Centre for the History of Music in Britain, the Empire and the Commonwealth: 9–10.

- ^ Kroeger, Karl (2001). "Valentine, John". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 26. London: Macmillan. pp. 207–8. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- ^ Who's who in Music. Fourth Edition. 1962. p.229

- ^ Dove, R. H. (1982) A Bellringer's Guide to the Church Bells of Britain and Ringing Peals of the World, 6th ed. Aldershot: Viggers

- ^ "Richard III Tomb and Burial". Leicester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Richard III: Leicester Cathedral reburial service for king". BBC News. 26 March 2015.

- ^ Gannon, Megan (19 September 2013). "Stately Tomb Design for Richard III's Reburial Revealed". LiveScience.

- ^ "Richard III: Making of the Tomb". James Elliott. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Portfolio: Richard III Coat of Arms for tombstone in Leicester Cathedral". Greenaway Mosaics. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Tomb Design". King Richard in Leicester. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

External links[edit]

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Church of England church buildings in Leicester

- Buildings and structures in Leicester

- Tourist attractions in Leicestershire

- Grade II* listed churches in Leicestershire

- Grade II* listed cathedrals

- Church of England church buildings in Leicestershire

- English Gothic architecture in Leicestershire

- J. L. Pearson buildings

- Diocese of Leicester