- This article describes historical escape routes for American slaves. See Public transportation for underground rail systems in the literal sense.

The Underground Railroad is a network of disparate historical routes used by African-American slaves to escape the United States and slavery by reaching freedom in Canada or other foreign territories. Today many of the stations along the "railroads" serve as museums and memorials to the former slaves' journey north.

Understand[edit]

- See also: Early history of the United States

From its birth as an independent nation in 1776 until the outbreak of Civil War over the issue in 1861, the United States was a nation where the institution of slavery caused bitter divisions. In the South, in particular the narrow region known as the Black Belt, slavery was the linchpin of an agrarian economy fueled by massive plantations of cotton and other labor-intensive crops. Meanwhile, to the north lay states such as Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and all of New England, where slavery was illegal and an abolitionist movement morally (and economically) opposed to slavery thrived. Between them lay what were called the "border states", sprawled west to east across the middle of the country from Missouri through Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia to Delaware, where slavery was legal but controversially so, with abolitionist sympathies not unknown among the population.

By the mid-19th century, the fragile stalemate that had characterized North-South relations in earlier decades had given way to increasing tensions. A major flashpoint was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a federal law which allowed escaped slaves discovered in free states to be forcibly transported back to enslavement in the South. In the Northern states, which had already ended slavery within their own borders, the new law was perceived as a massive affront — all the more so as tales of violent abductions by professional slavecatchers began to spread among the public. As federal law could be applied to otherwise-free states over local objections, any escaped slaves who reached northern states suddenly had good reason to continue toward Canada, where slavery had long been outlawed — and various groups quickly found motivation, as a matter of principle or religious belief, to take substantial risks to assist their northward exodus.

Various routes were used by black slaves to escape to freedom. Some fled south from Texas to Mexico or from Florida to various points in the Caribbean, but the vast majority of routes headed north through free states into Canada or other British territories. A few fled across New Brunswick to Nova Scotia (an Africville ghetto existed in Halifax until the 1960s) but the shortest, most popular routes crossed Ohio, which separated slavery in Kentucky from freedom across Lake Erie in Upper Canada.

This exodus coincides with a huge speculative boom in construction of passenger rail as new technology (the Grand Trunk mainline from Montreal through Toronto opened in 1856), so this loosely-knit intermodal network readily adopted rail terminology. Those recruiting slaves to seek freedom were "agents", the hiding or resting stations along the way were "stations" with their homeowners "stationmasters" and those funding the efforts "stockholders". Abolitionist leaders were the "conductors", of whom the most famous was former slave Harriet Tubman, lauded for her efforts in leading three hundred from Maryland and Delaware through Philadelphia and northward across New York State to freedom in Canada. In some sections, "passengers" travelled by foot or concealed in horse carts heading north on dark winter nights; in others they travelled by boat or by conventional rail. Religious groups (such as the Quakers, the Society of Friends) were prominent in the abolitionist movement and songs popular among slaves referenced the biblical Exodus from Egypt. Effectively, Tubman was "Moses" and the Big Dipper and north star Polaris pointed to the promised land.

The Underground Railroad was relatively short-lived: the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 made a war zone out of much of the border states, rendering the already dangerous passage even more so while largely eliminating the need for an onward exodus from northern states to Canada; by 1865, the war was over and slavery had been eliminated nationwide. Still, it's remembered as a pivotal chapter in American history in general and African-American history in particular, with many former stations and other sites preserved as museums or historical attractions.

Prepare[edit]

While there are various routes and substantial variation in distance, the exodus following the path of Harriet Tubman covers more than 500 mi (800 km) from Maryland and Delaware through Pennsylvania and New York to Ontario, Canada.

Historically, it was possible and relatively easy for citizens of either country to cross the U.S.-Canada border without a passport. In the 21st century, this is largely no longer true; border security has become more strict in the post-September 11, 2001 era.

Today, US nationals require a passport, U.S. passport card, Trusted Traveler Program card, or an enhanced driver’s license in order to return to the United States from Canada. Additional requirements apply to US permanent residents and third-country nationals; see the individual country articles (Canada § Get in and United States of America § Get in) or check the Canadian rules and U.S. rules for the documents required.

While the routes described here may be completed mostly overland, a historically-accurate portrayal of transport in the steam era would find road travel lagging dismally far behind the steam railways and ships which were the marvels of their day. The roads, such as they were, were little more than muddy dirt trails fit at best for a horse and cart; it was often more rapid to sail along the Atlantic Seaboard instead of attempting an equivalent overland route. A historically true Underground Railroad trip would be a bizarre intermodal mix of everything from horse carts to river barges to primitive freight trains to fleeing on foot or swimming across the Mississippi. At some points where routes historically crossed the Great Lakes, there is no scheduled ferry today.

The various books written after the Civil War (such as Wilbur Henry Siebert's The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom: A comprehensive history) describe hundreds of parallel routes and countless old homes which might have housed a "station" in the heyday of the exodus northward, but there is inherently no complete list of everything. As the network operated clandestinely, few contemporaneous records indicate with any certitude what exact role each individual figure or venue played — if any — in the antebellum era. Most of the original "stations" are merely old houses which look like any other home of the era; of those still standing, many are no longer preserved in a historically-accurate manner or are private residences which are no longer open to the voyager. A local or national historic register may list a dozen properties in a single county, but only a small minority are historic churches, museums, monuments or landmarks which invite visitors to do anything more than drive by and glimpse briefly from the outside.

This article lists many of the highlights but will inherently never be comprehensive.

Get in[edit]

The most common points of entry to the Underground Railroad network were border states which represented the division between free and slave: Maryland; Virginia, including what's now West Virginia; and Kentucky. Much of this territory is easily reached from Washington, D.C.. Tubman's journey, for instance, begins in Dorchester County, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and leads northward through Wilmington and Philadelphia.

| “ | I'll meet you in the morning. I'm bound for the promised land. | ” |

—Harriet Tubman | ||

Go[edit]

There are multiple routes and multiple points of departure to board this train; those listed here are merely notable examples.

Tubman's Pennsylvania, Auburn and Niagara Railroad[edit]

This route leads through Pennsylvania and New York, through various sites associated with Underground Rail "conductor" Harriet Tubman (escaped 1849, active until 1860) and her contemporaries. Born a slave in Dorchester County, Maryland, Tubman was beaten and whipped by her childhood masters; she escaped to Philadelphia in 1849. Returning to Maryland to rescue her family, she ultimately guided dozens of other slaves to freedom, travelling by night in extreme secrecy.

Maryland[edit]

Cambridge, Maryland — Tubman's birthplace, and the starting point of her route — is separated from Washington, D.C. by Chesapeake Bay and is approximately 90 mi (140 km) southeast of the capital via US 50:

- 1 Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument, 4068 Golden Hill Rd., Church Creek (10.7 miles/17.2 km south of Cambridge via State Routes 16 and 335), ☏ +1 410 221-2290. Daily 9AM-5PM. 17-acre (7 ha) national monument with a visitor center containing exhibits on Tubman's early life and exploits as an Underground Railroad conductor. Adjacent to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, this landscape has changed little from the days of the Underground Railroad. Free.

- 2 Harriet Tubman Organization, 424 Race St., Cambridge, ☏ +1 410 228-0401. Situated in a period building in downtown Cambridge is this museum of historic memorabilia open by appointment. There's also an attached community center with a full slate of cultural and educational programming regarding Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad.

Delaware[edit]

As described to Wilbur Siebert in 1897, the portion of Tubman's path from 1 Cambridge north to Philadelphia appears to be a 120 mi (190 km) overland journey by road via 2 East New Market and 3 Poplar Neck to the Delaware state line, then via 4 Sandtown, 5 Willow Grove, 6 Camden, 7 Dover, 8 Smyrna, 9 Blackbird, 10 Odessa, 11 New Castle, and 12 Wilmington. An additional 30 mi (48 km) was required to reach 13 Philadelphia. The Delaware portion of the route is traced by the signed Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway, where various Underground Railroad sites are highlighted.

- 3 Appoquinimink Friends Meetinghouse, 624 Main St., Odessa. Open for services 1st & 3rd Su of each month, 10AM. 1785 brick Quaker house of prayer which served as a station on the Underground Railroad under John Hunn and Thomas Garrett. A second story had a removable panel leading to spaces under the eaves; a cellar was reached by a small side opening at ground level.

- 4 [formerly dead link] Old New Castle Court House, 211 Delaware St., New Castle, ☏ +1 302 323-4453. Tu-Sa 10AM-4:30PM, Su 1:30-4:30PM. One of the oldest surviving courthouses in the United States, built as meeting place of Delaware's colonial and first State Assembly (when New Castle was Delaware's capital, 1732-1777). Underground Railroad conductors Thomas Garrett and John Hunn were tried and convicted here in 1848 for violating the Fugitive Slave Act, bankrupting them with fines which only served to harden the feelings over slavery of all involved. Donation.

The dividing line between slave and free states was the Mason-Dixon line:

- 5 Mason-Dixon Line, Mason-Dixon Farm Market, 18166 Susquehanna Trail South, Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania. A concrete post marks the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania in Shrewsbury, where slaves were made free after crossing into Pennsylvania during the American Civil War. Farm market owners have stories to share about Underground Railroad houses and other slave stops between Maryland and Pennsylvania. Free to stand and take a picture with the concrete post marker.

Pennsylvania[edit]

The first "free" state on the route, Pennsylvania abolished slavery in 1847.

Philadelphia, the federal capital during much of George Washington's era, was a hotbed of abolitionism, and the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the state government in March 1780, was the first to prohibit further importation of slaves into a state. While a loophole exempted members of Congress at Philadelphia, George and Martha Washington (as slave owners) scrupulously avoided spending six months or more in Pennsylvania lest they be forced to give their slaves freedom. Ona Judge, the daughter of a slave inherited by Martha Washington, feared being taken forcibly back to Virginia at the end of Washington's presidency; with the aid of local free blacks and abolitionists she was put onto a ship to New Hampshire and liberty.

In 1849, Henry Brown (1815-1897) escaped Virginia slavery by arranging to have himself mailed in a wooden crate to abolitionists in Philadelphia. From there, he moved to England from 1850-1875 to escape the Fugitive Slave Act, becoming a magician, showman and outspoken abolitionist.

- 6 Johnson House Historical Site, 6306 Germantown Ave., Philadelphia, ☏ +1 215 438-1768. Sa 1PM-5PM year-round, Th-F 10AM-4PM from Feb 2-Jun 9 and Sep 7-Nov 24, M-W by appointment only. Tours leave every 60 minutes at 15 minutes past the hour, and the last tour departs at 3:15PM. Former safe house and tavern in the Germantown area, frequented by Harriet Tubman and William Still, one of 17 Underground Railroad stations in Pennsylvania listed in the local guide Underground Railroad: Trail to Freedom. Still was an African-American abolitionist, clerk and member of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Hour-long guided tours are offered. $8, seniors 55+ $6, children 12 and under $4.

- 7 Belmont Mansion, 2000 Belmont Mansion Dr., Philadelphia, ☏ +1 215 878-8844. Tu-F 11AM-5PM, summer weekends by appointment. Historic Philadelphia mansion with Underground Railroad museum. $7, student/senior $5.

- 8 Christiana Underground Railroad Center, 11 Green St., Christiana, ☏ +1 610 593-5340. M-F 9AM-4PM. In 1851, a group of 38 local African-Americans and white abolitionists attacked and killed Edward Gorsuch, a slaveowner from Maryland who had arrived in town pursuing four of his escaped slaves, and wounded two of his companions. They were charged with treason for violating the Fugitive Slave Law, and Zercher's Hotel is where the trial took place. Today, the former hotel is home to a museum recounting the history of what came to be known as the Resistance at Christiana. Free.

- 9 [dead link] Central Pennsylvania African American Museum, 119 N. 10th St., Reading, ☏ +1 610 371-8713, fax: +1 610 371-8739. W & F 10:30AM-1:30PM, Su closed, all other days by appointment. The former Bethel AME Church in Reading was once a station on the Underground Railroad, now it's a museum detailing the history of the black community and the Underground Railroad in Central Pennsylvania. $8, senior citizens and students with ID $6, children 5-12 $4, children 4 and under free. Guided tours $10.

- 10 William Goodridge House and Museum, 123 E. Philadelphia St., York, ☏ +1 717 848-3610. First F of each month 4PM-8PM, and by appointment. Born into slavery in Maryland, William C. Goodridge became a prominent businessman who is suspected to have hidden fugitive slaves in one of the freight cars of his railcar Reliance Line. His handsome two-and-a-half story brick row house on the outskirts of downtown York is now a museum dedicated to his life story.

While Pennsylvania does border Canada across Lake Erie in its northwesternmost corner, freedom seekers arriving from eastern cities generally continued overland through New York State to Canada. While Harriet Tubman would have fled directly north from Philadelphia, many other passengers were crossing into Pennsylvania at multiple points along the Mason-Dixon line where the state bordered Maryland and a portion of Virginia (now West Virginia). This created many parallel lines which led north through central and western Pennsylvania into New York State's Southern Tier.

- 1 Fairfield Inn 1757, 15 W. Main St., Fairfield (8 miles/13 km west of Gettysburg via Route 116), ☏ +1 717 642-5410. The oldest continuously operated inn in the Gettysburg area, dating to 1757. Slaves would hide on the third floor after crawling through openings and trap doors. Today, a window is cut out to reveal where the slaves hid when the inn was a "safe station" on the Underground Railroad. $160/night.

- 11 Old Jail, 175 E. King St., Chambersburg, ☏ +1 717 264-1667. Tu-Sa (May-Oct), Th-Sa (year-round): 10AM-4PM, last tour 3PM. Built in 1818, the jail survived an attack in which Chambersburg was burned by the Confederates in 1864. Five domed dungeons in the cellar had rings in the walls and floors to shackle recalcitrant prisoners; these cells may also have been secretly used to shelter runaway slaves enroute to freedom in the north. $5, children 6 and over $4, families $10.

- 12 Blairsville Underground Railroad History Center, 214 E. South Ln., Blairsville (17 miles/27 km south of Indiana, Pennsylvania via Route 119), ☏ +1 724 459-0580. May-Oct by appointment. The Second Baptist Church building post-dates the Underground Railroad by more than half a century — it was built in 1917 — but it is the oldest black-owned structure in the town of Blairsville, and today it serves as a historical museum with two exhibits related to slavery and emancipation: "Freedom in the Air" tells the story of the abolitionists of Indiana County and their efforts to assist fugitive slaves, while the title of "A Day in the Life of an Enslaved Child" is self-explanatory.

- 13 Freedom Road Cemetery, Freedom Rd., Loyalsock Township (1.5 miles/2.4 km north of Williamsport via Market Street and Bloomingrove Road). Daniel Hughes (1804-1880) was a raftsman who transported lumber from Williamsport to Havre de Grace, Maryland on the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, hiding runaway slaves in the hold of his barge on the return trip. His farm is now a tiny Civil War cemetery, the final resting spot of nine African-American soldiers. While there is a historic marker, this spot (renamed from Nigger Hollow to Freedom Road in 1936) is small and easy to miss.

The most popular option, however, was to follow the coast from Philadelphia to New York City en route to Albany or Boston.

New York State[edit]

Escaped slaves were on friendly turf in Upstate New York, one of the most staunchly abolitionist regions of the country.

- 14 [dead link] Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence, 194 Livingston Ave., Albany, ☏ +1 518 432-4432. Tours M-F 5-8PM, Sa noon-4PM or by appointment. Stephen Myers was a slave turned freedman and abolitionist who was a central figure in the local Underground Railroad goings-on, and of all the several houses he inhabited in Albany's Arbor Hill neighborhood in the mid-19th century, this is the only one that's still extant. The then-dilapidated house was saved from the wrecking ball in the 1970s and restoration work is ongoing, but for now, visitors can enjoy guided tours of the house and a small but worthwhile slate of museum exhibits on Myers, Dr. Thomas Elkins, and other prominent members of the Albany Vigilance Committee of abolitionists. $10, seniors $8, children 5-12 $5.

At Albany, multiple options existed. Fugitives could continue northward to Montreal or Quebec's Eastern Townships via Lake Champlain, or (more commonly) they could turn west along the Erie Canal line through Syracuse to Oswego, Rochester, Buffalo, or Niagara Falls.

- 15 Gerrit Smith Estate and Land Office, 5304 Oxbow Rd., Peterboro (9.1 miles/15.1 km east of Cazenovia via County Routes 28 and 25), ☏ +1 315 280-8828. Museum Sa Su 1-5PM, late May-late Aug, grounds daily dawn-dusk. Smith was president of the New York Anti-Slavery Society (1836-1839) and a "station master" on the Underground Railroad in the 1840s and 1850s. The sprawling estate where he lived throughout his life is now a museum complex with interior and exterior exhibits on freedom seekers, Gerrit Smith's wealth, philanthropy and family, and the Underground Railroad.

Syracuse was an abolitionist stronghold whose central location made it a "great central depot on the Underground Railroad" through which many slaves passed on their way to liberty.

- 16 Jerry Rescue Monument, Clinton Square, Syracuse. During the 1851 state convention of the anti-slavery Liberty Party, an angry mob of several hundred abolitionists busted escaped slave William "Jerry" Henry out of jail; from there he was clandestinely transported to the town of Mexico, New York and concealed there until he could be taken aboard a British-Canadian lumber ship one dark night for transport across Lake Ontario to Kingston. Nine of those who aided in the escape (including two ministers of religion) fled to Canada; of the twenty-nine who were put on trial in Syracuse, all but one was acquitted. The jail no longer stands, but there is a monument on Clinton Square commemorating these momentous events.

In this area, passengers arriving from Pennsylvania across the Southern Tier travelled through Ithaca and Cayuga Lake to join the main route at Auburn, a town west of Syracuse on US 20. Harriet Tubman lived here starting in 1859, establishing a home for the aged.

- 17 St. James AME Zion Church, 116 Cleveland Ave., Ithaca, ☏ +1 607 272-4053. M-Sa 9AM-5PM or by appointment. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church was established in the early 1800s in New York City as an offshoot of the Methodist Episcopal Church to serve black parishioners who at the time encountered overt racism in existing churches. St. James, founded 1836, was a station on the Underground Railroad, hosted services attended by such 19th-century African-American luminaries as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, and in 1906 hosted a group of students founding Alpha Phi Alpha, the nation's oldest official black fraternity.

- 18 Harriet Tubman Home, 180 South St., Auburn, ☏ +1 315 252-2081. Tu-F 10AM-4PM, Sa 10AM-3PM. Known as "The Moses of Her People," Tubman settled in Auburn after the Civil War in this modest but handsome brick house, where she also operated a home for aged and indigent African-Americans. Today it's a museum that houses a collection of historical memorabilia. $4.50, seniors (60+) and college students $3, children 6-17 $1.50.

- 19 Thompson AME Zion Church, 33 Parker St., Auburn. Closed for restorations. An 1891-era African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church where Harriet Tubman attended services; she later deeded the aforementioned Home for the Aged to the church to manage after her death.

- 20 Fort Hill Cemetery, 19 Fort St., Auburn, ☏ +1 315 253-8132. M-F 9AM-1PM. Set on a hill overlooking Auburn, this site was used for burial mounds by Native Americans as early as 1100 AD. It includes the burial sites of Harriet Tubman as well as a variety of other local historic luminaries. The website includes a printable map and self-guided walking tour.

The main route continues westward toward Buffalo and Niagara Falls, which remains the busiest set of crossings on the Ontario-New York border today. (Alternate routes involved crossing Lake Ontario from Oswego or Rochester.)

- 21 Palmyra Historical Museum, 132 Market St., Palmyra, ☏ +1 315 597-6981. Tu-Th 10AM-5PM year-round, Tu-Sa 11AM-4PM in high season. One of five separate museums in the Historic Palmyra Museum Complex; each presents a different aspect of life in old Palmyra. The flagship museum houses various permanent exhibits on local history, including the Underground Railroad. $3, seniors $2, kids under 12 free.

Rochester, home to Frederick Douglass and a bevy of other abolitionists, also afforded escapees passage to Canada, if they were able to make their way to Kelsey's Landing just north of the Lower Falls of the Genesee. There were a number of safehouses in the city, including Douglass' own home.

- 22 Rochester Museum and Science Center, 657 East Ave., Rochester, ☏ +1 585 271-4320. M-Sa 9AM-5PM, Su 11AM-5PM. Rochester's interactive science museum has a semi-permanent exhibit called Flight to Freedom: Rochester’s Underground Railroad. It lets kids get a glimpse of the story of the Railroad through the eyes of a fictional child escaping to Canada. Adults $15, seniors/college $14, ages 3-18 $13, under 3 free.

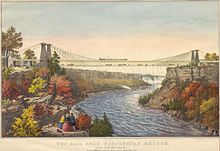

Ontario's entire international boundary is water. There were a few ferries in places like Buffalo, but infrastructure was sparse. Niagara Falls had an 825 ft (251 m) railway suspension bridge joining the Canadian and U.S. twin towns below the falls.

- 23 Castellani Art Museum, 5795 Lewiston Rd., Niagara Falls, ☏ +1 716 286-8200, fax: +1 716 286-8289. Tu-Sa 11AM-5PM, Su 1PM-5PM. Part of the permanent collection of Niagara University's campus art gallery is "Freedom Crossing: The Underground Railroad in Greater Niagara", telling the story of the Underground Railroad movement on the Niagara Frontier.

- 24 [dead link] Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Interpretive Center, 2245 Whirlpool St., Niagara Falls (next to the Whirlpool Bridge and the Amtrak station). Tu-W & F-Sa 10AM-6PM, Th 10AM-8PM, Su 10AM-4PM. The former U.S. custom house (1863-1962) is now a museum dedicated to the Niagara Frontier's Underground Railroad history. Exhibits include a recreation of the "Cataract House", one of the largest hotels in Niagara Falls at the time whose largely African-American waitstaff was instrumental in helping escaped slaves on the last leg of their journey. $10, high school and college students with ID $8, children 6-12 $6.

- 25 Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge site. Built in 1848, this first suspension bridge across the Niagara River was the last leg in Harriet Tubman's own journey from slavery in Maryland to freedom in Canada, and she would return many times over the next decade as a "conductor" for other escapees. After 1855, when it was repurposed as a railroad bridge, slaves would be smuggled across the border in cattle or baggage cars. The site is now the Whirlpool Bridge.

To the north is Lewiston, a possible crossing point to Niagara-on-the-Lake in Canada:

- 26 [dead link] First Presbyterian Church and Village Cemetery, 505 Cayuga St., Lewiston, ☏ +1 716 794-4945. Open for services Su 11:15AM. A sculpture in front of Lewiston's oldest church (erected 1835) commemorates the prominent role it played in the Underground Railroad.

- 27 Freedom Crossing Monument (At Lewiston Landing Park, on the west side of N. Water St. between Center and Onondaga Sts.). An outdoor sculpture on the bank of the Niagara River depicting local Underground Railroad stationmaster Josiah Tryon spiriting away a family of freedom seekers on their final approach to Canada. Tryon operated his station out of the House of the Seven Cellars, his brother's residence just north of the village center (still extant but not open to the public) where a series of steps led from a multi-level network of interconnecting basements to the riverbank, from whence Tryon would ferry the escapees across the river as depicted in the sculpture.

To the south is Buffalo, opposite Fort Erie in Ontario:

- 28 Michigan Street Baptist Church, 511 Michigan Ave., Buffalo, ☏ +1 716 854-7976. The oldest property continuously owned, operated, and occupied by African-Americans in Buffalo, this historic church served as a station on the Underground Railroad. Historical tours are offered by appointment. $5.

- 29 Broderick Park (on the Niagara River at the end of West Ferry Street), ☏ +1 716 218-0303. Many years before the Peace Bridge was constructed to the south, the connection between Buffalo and Fort Erie was by ferry, and many fugitive slaves crossed the river to Canada in this way. There is a memorial and historic plaques onsite illustrating the site's significance, as well as historical reenactments from time to time.

As mentioned earlier, some escapees instead approached from the south, passing from western Pennsylvania through the Southern Tier toward the border.

- 30 [formerly dead link] Howe-Prescott Pioneer House, 3031 Route 98 South, Franklinville, ☏ +1 716 676-2590. Su Jun-Aug by appointment. Built circa 1814 by a family of prominent abolitionists, this house served as a station on the Underground Railroad in the years before the Civil War. The Ischua Valley Historical Society has restored the site as a pioneer homestead, with exhibits and demonstrations illustrating life in the early days of white settlement in Western New York.

Ontario[edit]

The end of the line is St. Catharines in Ontario's Niagara Region.

- 31 British Methodist Episcopal Church, Salem Chapel, 92 Geneva St., St. Catharines, ☏ +1 905-682-0993. Services Su 11AM, guided tours by appointment. St. Catharines was one of the principal Canadian cities to be settled by escaped American slaves — Harriet Tubman and her family lived there for about ten years before returning to the U.S. and settling in Auburn, New York — and this simple but handsome wooden church was constructed in 1851 to serve as their place of worship. It's now listed as a National Historic Site of Canada, and several plaques are placed outside the building explaining its history. $5 to $7 donation per person recommended.

- 32 Negro Burial Ground, Niagara-on-the-Lake (east side of Mississauga St. between John and Mary Sts.), ☏ +1 905-468-3266. The Niagara Baptist Church — the house of worship of Niagara-on-the-Lake's community of Underground Railroad escapees — is long gone, but the cemetery on its former site, where many of its congregants were buried, remains. While the site doesn't have its own website, more information can be found at Friends of the Forgotten and Ontario Heritage Trust.

- 33 Griffin House, 733 Mineral Springs Rd., Ancaster, ☏ +1 905-648-8144. Su 1-4PM, Jul-Sep. Fugitive Virginia slave Enerals Griffin escaped to Canada in 1834 and settled in the town of Ancaster as a farmer; his rough-hewn log farmhouse has now been restored to its original period appearance. Walking trails out back lead into the lovely Dundas Valley and a series of waterfalls. Donation.

The Niagara Region is now part of the Golden Horseshoe, the most densely-populated portion of the province. Further afield, the Toronto Transit Commission (☏ +1 416-393-INFO (4636)) has run an annual Underground Freedom Train Ride to commemorate Emancipation Day. The train leaves Union Station in downtown Toronto in time to reach Sheppard West (the former northwest end of the line) just after midnight on August 1. Celebrations include singing, poetry readings and drum playing.

The Ohio Line[edit]

Kentucky, a slave state, is separated from Indiana and Ohio by the Ohio River. Because of Ohio's location (which borders the southernmost point in Canada across Lake Erie), multiple parallel lines led north across the state to freedom in Upper Canada. Some passed through Indiana to Ohio, while others entered Ohio directly from Kentucky.

Indiana[edit]

Directly across the river from Louisville, Kentucky, the town of New Albany served as one of the principal river crossing points for fugitives heading north.

- 34 Town Clock Church, 300 E. Main St., New Albany, ☏ +1 812 945-3814. Services Su 11AM, tours by appointment. This restored 1852 Greek Revival church used to house the Second Presbyterian Church, a station of the Underground Railroad whose distinctive clock tower signaled New Albany's location to the Ohio River boatmen. Now home to an African-American congregation and the subject of fundraising efforts aimed at restoring the building to its original splendor after years of neglect, the church hosts regular services, guided tours by appointment, and occasional historical commemorations and other events.

Indianapolis is 130 mi (210 km) to the north; Fishers and Westfield are among its suburbs.

- 35 Conner Prairie Museum, 13400 Allisonville Rd., Fishers, ☏ +1 317 776-6000, toll-free: +1-800 966-1836. Check website for schedule. Home of the "Follow the North Star" theatrical program-cum-historical reenactment, where participants travel back to the year 1836 and assume the role of fugitive slaves seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad. Learn by becoming a fugitive slave in an interactive encounter where museum staff become the slave hunters, friendly Quakers, freed slaves and railroad conductors that decide your fate. $20.

Westfield is a great town for walking tours; the Westfield-Washington Historical Society (see below) can provide background information. Historic Indiana Ghost Walks & Tours (☏ +1 317 840-6456) also covers "ghosts of the Underground Railroad" on one of its Westfield tours (reservations required, check schedule).

- 36 Westfield-Washington Historical Society & Museum, 130 Penn St., Westfield, ☏ +1 317 804-5365. Sa 10AM-2PM, or by appointment. Settled by staunchly abolitionist Quakers, it should come as no surprise that Westfield was one of Indiana's Underground Railroad hotbeds. Learn all about those and other elements of local history in this museum. Donation.

From the Indianapolis area, the route splits: you can either head east into Ohio or north into Michigan.

- 37 Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site, 201 US Route 27 North, Fountain City (9.2 miles/14.8 km north of Richmond via US 27), ☏ +1 765 847-1691. Tu-Su 10AM-5PM. The "Grand Central Station" of the Underground Railroad where three escape routes to the North converged is where Levi and Catharine Coffin lived and harbored more than 2,000 freedom seekers to safety. A family of well-to-do Quakers, the Coffins' residence is an ample Federal-style brick home that's been restored to its period appearance and opened to guided tours. A full calendar of events also take place. $10, seniors (60+) $8, children 3-17 $5.

Another option is to head north from Kentucky directly into Ohio.

Ohio[edit]

The stations listed here form a meandering line through Ohio's major cities — Cincinnati to Dayton to Columbus to Cleveland to Toledo — and around Lake Erie to Detroit, a journey of approximately 800 mi (1,300 km). In practice, Underground Railroad passengers would head due north and cross Lake Erie at the first possible opportunity via any of multiple parallel routes.

From Lexington, Kentucky, you head north 85 mi (137 km) on this freedom train to Covington. Directly across the Ohio River and the state line is Cincinnati, one of many points at which thousands crossed into the North in search of freedom.

- 38 National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, 50 East Freedom Way, Cincinnati, ☏ +1 513 333-7500. Tu-Su 11AM-5PM. Among the most comprehensive resources of Underground Railroad-related information anywhere in the country, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center should be at the top of the list for any history buff retracing the escapees' perilous journey. The experience at this "museum of conscience" includes everything from genuine historical artifacts (including a "slave pen" built c. 1830, the only known extant one of these small log cabins once used to house slaves prior to auction) to films and theatrical performances to archival research materials, relating not only the story of the Underground Railroad but the entirety of the African-American struggle for freedom from the Colonial era through the Civil War, Jim Crow, and the modern day. $12, seniors $10, children $8.

30 mi (48 km) to the east, Williamsburg and Clermont County were home to multiple stations on the Underground Railroad. 55 mi (89 km) north is Springboro, just south of Dayton in Warren County.

- 39 Springboro Historical Society Museum, 110 S. Main St., Springboro, ☏ +1 937 748-0916. F-Sa 11AM-3PM. This small museum details Springboro's storied past as a vital stop on the Underground Railroad. While you're in town, stop by the Chamber of Commerce (325 S. Main St.) and pick up a brochure with a self-guided walking tour of 27 local "stations" on the Railroad, the most of any city in Ohio, many of which still stand today.

East of Dayton, one former station is now a tavern.

- 1 Ye Olde Trail Tavern, 228 Xenia Ave., Yellow Springs, ☏ +1 937 767-7448. Su-Th 11AM-10PM, F-Sa 11AM-11PM; closes an hour early Oct-Mar. Kick back with a cold beer and nosh on bar snacks with an upscale twist in this 1844 log cabin that was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. Mains $8-12.

Continue east 110 mi (180 km) through Columbus and onward to Zanesville, then detour north via Route 60.

- 40 Prospect Place, 12150 Main St., Trinway (16 miles/26 km north of Zanesville via Route 60), ☏ +1 740 221-4175. Sa-Su noon-4PM, Mar 17-Nov 4. An ongoing historic renovation aims to bring this 29-room Italianate-style mansion back to its appearance in the 1850s and '60s, when it served as the home of railroad baron, local politico, and abolitionist George Willison Adams — not to mention one of the area's most important Underground Railroad stations. The restored portions of the mansion are open for self-guided tours (weather-dependent; the building is not air-conditioned and the upper floors can get stifling in summer, so call ahead on hot days to make sure they're open), and Prospect Place is also home to the G. W. Adams Educational Center, with a full calendar of events,

Another 110 mi (180 km) to the northeast is Alliance.

- 41 Haines House Underground Railroad Museum, 186 W. Market St., Alliance, ☏ +1 330 829-4668. Open for tours the first weekend of each month: Sa 10AM-noon; Su 1PM-3PM. Sarah and Ridgeway Haines, daughter and son-in-law of one of the town's first settlers, operated an Underground Railroad station out of their stately Federal-style home, now fully restored and open to the public as a museum. Tour the lovely Victorian parlor, the early 19th century kitchen, the bedrooms, and the attic where fugitive slaves were hidden. Check out exhibits related to local Underground Railroad history and the preservation of the house. $3.

The next town to the north is 42 Kent, the home of Kent State University, which was a waypoint on the Underground Railroad back when the village was still named Franklin Mills. 36 mi (58 km) further north is the Lake Erie shoreline, east of Cleveland. From there, travellers had a few possible options: attempt to cross Lake Erie directly into Canada, head east through western Pennsylvania and onward to Buffalo...

- 43 Hubbard House Underground Railroad Museum, 1603 Walnut Blvd., Ashtabula, ☏ +1 440 964-8168. F-Su 1PM-5PM, Memorial Day through Labor Day, or by appointment. William and Catharine Hubbard's circa-1841 farmhouse was one of the Underground Railroad's northern termini — directly behind the house is Lake Erie, and directly across the lake is Canada — and today it's the only one that's open to the public for tours. Peruse exhibits on local Underground Railroad and Civil War history set in environs restored to their 1840s appearance, complete with authentic antique furnishings. $5, seniors $4, children 6 and over $3.

...or turn west.

- 44 Lorain Underground Railroad Station 100 Monument, 100 Black River Ln., Lorain (At Black River Landing), ☏ +1 440 328-2336. Not a station, but rather a historic monument that honors Lee Howard Dobbins, a 4-year-old escaped slave, orphaned en route to freedom with his mother, who later died in the home of the local family who took him in. A large relief sculpture, inscribed with an inspirational poem read at the child's funeral (which was attended by a thousand people), is surrounded by a contemplative garden.

West of Lorain is Sandusky, one of the foremost jumping-off points for escaped slaves on the final stage of their journey to freedom. Among those who set off across Lake Erie from here toward Canada was Josiah Henson, whose autobiography served as inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe's famous novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Modern-day voyagers can retrace that journey via the MV Pelee Islander, a seasonal ferry plying the route from Sandusky to Leamington and Kingsville, Ontario, or else stop in to the Lake Erie Shores & Islands Welcome Center at 4424 Milan Rd. and pick up a brochure with a free self-guided walking tour of Sandusky-area Underground Railroad sites.

- 45 Maritime Museum of Sandusky, 125 Meigs St., Sandusky, ☏ +1 419 624-0274. Year-round F-Sa 10AM-4PM, Su noon-4PM; also Tu-Th 10AM-4PM Jun-Aug. This museum interprets Sandusky's prominent history as a lake port and transportation nexus through interactive exhibits and educational programs on a number of topics, including the passenger steamers whose owners were among the large number of locals active in the Underground Railroad. $6, seniors 62+ and children under 12 $5, families $14.

- 46 Path to Freedom Sculpture, Facer Park, 255 E. Water St., Sandusky, ☏ +1 419 624-0274. In the center of a small harborfront park in downtown Sandusky stands this life-size sculpture of an African-American man, woman and child bounding with arms outstretched toward the waterfront and freedom, fashioned symbolically out of 800 ft (240 m) of iron chains.

As an alternative to crossing the lake here, voyagers could continue westward through Toledo to Detroit.

Michigan[edit]

Detroit was the last American stop for travellers on this route: directly across the river lies Windsor, Ontario.

- 47 First Living Museum, 33 E. Forest Ave., Detroit, ☏ +1 313 831-4080. Call museum for schedule of tours. The museum housed in the First Congregational Church of Detroit features a 90-minute "Flight to Freedom" reenactment that simulates an escape from slavery on the Underground Railroad: visitors are first shackled with wrist bands, then led to freedom by a "conductor" while hiding from bounty hunters, crossing the Ohio River to seek refuge in Levi Coffin's abolitionist safe house in Indiana, and finally arriving to "Midnight" — the code name for Detroit in Railroad parlance. $15, youth and seniors $12.

- 48 Mariners' Church, 170 E. Jefferson Ave., Detroit, ☏ +1 313 259-2206. Services Su 8:30AM & 11AM. An 1849 limestone church known primarily for serving Great Lakes sailors and memorializing crew lost at sea. In 1955, while moving the church to make room for a new civic center, workers discovered an Underground Railroad tunnel under the building.

If Detroit was "Midnight" on the Underground Railroad, Windsor was "Dawn". A literal underground railroad does stretch across the river from Detroit to Windsor, along with another one to the north between Port Huron and Sarnia, but since 2004 the tunnels have served only freight. A ferry crosses here for large trucks only. An underground road tunnel also runs to Windsor, complete with a municipal Tunnel Bus service (C$4/person, one way).

- Gateway to Freedom International Memorial. Historians estimate that as many as 45,000 runaway slaves passed through Detroit-Windsor on the Underground Railroad, and this pair of monuments spanning both sides of the riverfront pays homage to the local citizens who defied the law to provide safety to the fugitives. Sculpted by Ed Dwight, Jr. (the first African-American accepted into the U.S. astronaut training program), the 49 Gateway to Freedom Memorial at Hart Plaza in Detroit depicts eight larger-than-life figures — including George DeBaptiste, an African-American conductor of local prominence — gazing toward the promised land of Canada. On the Windsor side, at the Civic Esplanade, the 50 Tower of Freedom depicts four more bronze figures with arms upraised in relief, backed by a 20 ft (6.1 m) marble monolith.

There is a safehouse 35 mi (56 km) north of Detroit (on the U.S. side) in Washington Township:

- 51 Loren Andrus Octagon House, 57500 Van Dyke Ave., Washington Township, ☏ +1 586 781-0084. 1-4PM on 3rd Sunday of month (Mar-Oct) or by appointment. Erected in 1860, the historic home of canal and railroad surveyor Loren Andrus served as a community meeting place and station during the latter days of the Underground Railroad, its architecture capturing attention with its unusual symmetry and serving as a metaphor for a community that bridges yesterday and tomorrow. One-hour guided tours lead through the house's restored interior and include exhibits relevant to its history. $5.

Ontario[edit]

The most period-appropriate way to replicate the crossing into Canada used to be the Bluewater Ferry across the St. Clair River between Marine City, Michigan and Sombra, Ontario. The ferry no longer operates. Instead, cross from Detroit to Windsor via the Ambassador Bridge or the aforementioned tunnel, or else detour north to the Blue Water Bridge between Port Huron and Sarnia.

- 52 Sandwich First Baptist Church, 3652 Peter St., Windsor, ☏ +1 519-252-4917. Services Su 10AM, tours by appointment. The oldest existing majority-Black church in Canada, erected in 1847 by early Underground Railroad refugees, Sandwich First Baptist was often the first Canadian stop for escapees after crossing the river from Detroit: a series of hidden tunnels and passageways led from the riverbank to the church to keep folks away from the prying eyes of slave catchers, the more daring of whom would cross the border in violation of Canadian law in pursuit of escaped slaves. Modern-day visitors can still see the trapdoor in the floor of the church.

- 1 Emancipation Day Celebration, Lanspeary Park, Windsor. Held annually on the first Saturday and Sunday in August from 2-10PM, "The Greatest Freedom Show on Earth" commemorates the Emancipation Act of 1833, which abolished slavery in Canada as well as throughout the British Empire. Live music, yummy food, and family-friendly entertainment abound. Admission free, "entertainment area" with live music $5 per person/$20 per family.

Amherstburg, just south of Windsor, was also a destination for runaway slaves.

- 53 Amherstburg Freedom Museum, 277 King St., Amherstburg, ☏ +1 519-736-5433, toll-free: +1-800-713-6336. Tu-F noon-5PM, Sa Su 1-5PM. Telling the story of the African-Canadian experience in Essex County is not only the museum itself, with a wealth of historic artifacts and educational exhibits, but also the Taylor Log Cabin, the home of an early black resident restored to its mid-19th century appearance, and also the Nazrey AME Church, a National Historic Site of Canada. A wealth of events takes place in the onsite cultural centre. Adult $7.50, seniors & students $6.50.

- 54 John Freeman Walls Historic Site and Underground Railroad Museum, 859 Puce Rd., Lakeshore (29 km/18 miles east of downtown Windsor via Highway 401), ☏ +1 519-727-6555, fax: +1 519-727-5793. Tu-Sa 10:30AM-3PM in summer, by appointment other times. Historical museum situated in the 1846 log-cabin home of John Freeman Walls, a fugitive slave from North Carolina turned Underground Railroad stationmaster and pillar of the small community of Puce, Ontario (now part of the Town of Lakeshore). Dr. Bryan Walls, the museum's curator and a descendant of the owner, wrote a book entitled The Road that Leads to Somewhere detailing the history of his family and others in the community.

Following the signed African-Canadian Heritage Tour eastward from Windsor, you soon come to the so-called "Black Mecca" of Chatham, which after the Underground Railroad began quickly became — and to a certain extent remains — a bustling centre of African-Canadian life.

- 55 Chatham-Kent Museum, 75 William St. N., Chatham, ☏ +1 519-360-1998. W-F 1-7PM, Sa Su 11AM-4PM. One of the highlights of the collection at this all-purpose local history museum are some of the personal effects of American abolitionist John Brown, whose failed 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia was contemporaneous with the height of the Underground Railroad era and stoked tensions on both sides of the slavery divide in the runup to the Civil War.

- 56 Black Mecca Museum, 177 King St. E., Chatham, ☏ +1 519-352-3565. M-F 10AM-3PM, till 4PM Jul-Aug. Researchers, take note: the Black Mecca Museum was founded as a home for the expansive archives of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society detailing Chatham's rich African-Canadian history. If that doesn't sound like your thing, there are also engaging exhibits of historic artifacts, as well as guided walking tours (call to schedule) that take in points of interest relevant to local black history. Self-guided tours free, guided tours $6.

- 57 First Baptist Church, 135 King Street East, Chatham-Kent, Ontario N7M 3N1 (Located next to the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum.), ☏ +1 519-352-9553. Founded in the 1840s, the First Baptist Church was the site of clandestine meetings held by abolitionist John Brown leading up to the ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry.

Other historic settlements in Kent County include Dresden and North Buxton, Ontario, which are home to two of the most well-known Underground Railroad sites in Canada:

- 58 Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site, 29251 Uncle Tom's Rd., Dresden (27 km/17 miles north of Chatham via County Roads 2 and 28), ☏ +1 519-683-2978. Tu-Sa 10AM-4PM, Su noon-4PM, May 19-Oct 27; also Mon 10AM-4PM Jul-Aug; Oct 28-May 18 by appointment. This sprawling open-air museum complex is centred on the restored home of Josiah Henson, a former slave turned author, abolitionist, and minister whose autobiography was the inspiration for the title character in Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. But that's not the end of the story: a restored sawmill, smokehouse, the circa-1850 Pioneer Church, and the Henson family cemetery are just some of the authentic period buildings preserved from the Dawn Settlement of former slaves. Historical artifacts, educational exhibits, multimedia presentations, and special events abound.

- 59 Buxton National Historic Site & Museum, 21975 A.D. Shadd Rd., North Buxton (16 km/10 miles south of Chatham via County Roads 2, 27, and 14), ☏ +1 519-352-4799, fax: +1 519-352-8561. Daily 10AM-4:30PM, Jul-Aug; W-Su 1PM-4:30PM, May & Sep; M-F 1PM-4:30PM, Oct-Apr. The Elgin Settlement was a haven for fugitive slaves and free blacks founded in 1849, and this museum complex — along with the annual Buxton Homecoming cultural festival in September — pays homage to the community that planted its roots here. In addition to the main museum building (containing historical exhibits) are authentic restored buildings from the former settlement: a log cabin, a barn, and a schoolhouse. $6, seniors and students $5, families $20.

Across the Land of Lincoln[edit]

Though Illinois was de jure a free state, Southern cultural influence and sympathy for the institution of slavery was very strong in its southernmost reaches (even to this day, the local culture in Cairo and other far-downstate communities bears more resemblance to the Mississippi Delta than Chicago). Thus, the fate of fugitive slaves passing through Illinois was variable: near the borders of Missouri and Kentucky the danger of being abducted and forcibly transported back to slavery was very high, while those who made it further north would notice a marked decrease in the local tolerance for slave catchers.

The Mississippi River was a popular Underground Railroad route in this part of the country; a voyager travelling north from Memphis would pass between the slave-holding states of Missouri and Kentucky to arrive 175 mi (282 km) later at Cairo, a fork in the river. From there, the Mississippi continued northward through St. Louis while the Ohio River ran along the Ohio-Kentucky border to Cincinnati and beyond.

- 60 Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum, 826 N. Second St., Memphis, Tennessee, ☏ +1 901 527-7711. Daily 10AM-4PM, till 5PM Jun-Aug. Built in 1849 by Jacob Burkle, a livestock trader and baker originally from Germany, this modest yet handsome house was long suspected to be a waypoint for Underground Railroad fugitives boarding Mississippi river boats. Now a museum, the house has been restored with period furnishings and contains interpretive exhibits. Make sure to go down into the basement, where the trap doors, tunnels and passages used to hide escaped slaves have been preserved. A three-hour historical sightseeing tour of thirty local sites is also offered for $45. $12.

Placing fugitives onto vessels on the Mississippi was a monumental risk that figured prominently in the literature of the era. There was even a "Reverse Underground Railroad" used by antebellum slave catchers to kidnap free blacks and fugitives from free states to sell them back into slavery.

Because of its location on the Mississippi River, St. Louis was directly on the boundary between slaveholding Missouri and abolitionist Illinois.

- 2 Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing, 28 E Grand Ave., St. Louis, Missouri, ☏ +1 314 584-6703. The Rev. John Berry Meachum of St. Louis' First African Baptist Church arrived in St. Louis in 1815 after purchasing his freedom from slavery. Ordered to stop holding classes in his church under an 1847 Missouri law prohibiting education of people of color, he instead circumvented the restriction by teaching on a Mississippi riverboat. His widow Mary Meachum was arrested early in the morning of May 21, 1855 with a small group of runaway slaves and their guides who were attempting to cross the Mississippi River to freedom. These events are commemorated each May with a historical reenactment of the attempted crossing by actors in period costume, along with poetry, music, dance, and dramatic performances. Even if you're not in town for the festival, you can still stop by the rest area alongside the St. Louis Riverfront Trail and take in the colorful wall mural and historic plaques.

Author Mark Twain, whose iconic novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) describes a freedom-seeking Mississippi voyage downriver to New Orleans, grew up in Hannibal, Missouri, a short distance upriver from St. Louis. Hannibal, in turn, is not far from Quincy, Illinois, where freedom seekers would often attempt to cross the Mississippi directly.

- 61 Dr. Richard Eells House, 415 Jersey St., Quincy, ☏ +1 217 223-1800. Sa 1PM-4PM, group tours by appointment. Connecticut-born Dr. Eells was active in the abolitionist movement and is credited with helping several hundred slaves flee from Missouri. In 1842, while providing aid to a fugitive swimming the river, Dr. Eells was spotted by a posse of slave hunters. Eells escaped, but was later arrested and charged with harboring a fugitive slave. His case (with a $400 fine) was unsuccessfully appealed as far as the U.S. Supreme Court, with the final appeal made by his estate after his demise. His 1835 Greek Revival-style house, four blocks from the Mississippi, has been restored to its original appearance and contains museum exhibits regarding the Eells case in particular and the Underground Railroad in general. $3.

70 mi (110 km) east of Quincy is Jacksonville, once a major crossroads of at least three different Underground Railroad routes, many of which carried passengers fleeing from St. Louis. Several of the former stations still stand. The Morgan County Historical Society runs a Sunday afternoon bus tour twice annually (spring and fall) from Illinois College to Woodlawn Farm with guides in period costume.

- 62 Beecher Hall, Illinois College, 1101 W. College Ave., Jacksonville, ☏ +1 217 245-3000. Founded in 1829, Illinois College was the first institution of postsecondary education in the state, and it quickly became a nexus of the local abolitionist community. The original building was renamed Beecher Hall in honor of the college's first president, Edward Beecher, brother of Uncle Tom's Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Tours of the campus are offered during the summer months (see website for schedule); while geared toward prospective students, they're open to all and offer an introduction to the history of the college.

- 63 Woodlawn Farm, 1463 Gierkie Ln., Jacksonville, ☏ +1 217 243-5938, ugrr@woodlawnfarm.com. W & Sa-Su 1PM-4PM, late May-late Sep, or by appointment. Pioneer settler Michael Huffaker built this handsome Greek Revival farmhouse circa 1840, and according to local tradition hid fugitive slaves there during the Underground Railroad era by disguising them as resident farmhands. Nowadays it's a living history museum where docents in period attire give guided tours of the restored interior, furnished with authentic antiques and family heirlooms. $4 suggested donation.

50 mi (80 km) further east is the state capital of 64 Springfield, the longtime home and final resting place of Abraham Lincoln. During the time of the Underground Railroad, he was a local attorney and rising star in the fledgling Republican Party who was most famous as Congressman Stephen Douglas' sparring partner in an 1858 statewide debate tour where slavery and other matters were discussed. However, Lincoln was soon catapulted from relative obscurity onto the national stage with his win in the 1860 Presidential election, going on to shepherd the nation through the Civil War and issue the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves once and for all.

From Springfield, one could turn north through Bloomington and Princeton to Chicago, or continue east through Indiana to Ohio or Michigan.

- 65 Owen Lovejoy Homestead, 905 E. Peru St., Princeton (21 miles/34 km west of Peru via US 6 or I-80), ☏ +1 815 879-9151. F-Sa 1PM-4PM, May-Sep or by appointment. The Rev. Owen Lovejoy (1811-1864) was one of the most prominent abolitionists in the state of Illinois and, along with Lincoln, a founding father of the Republican Party, not to mention the brother of newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy, whose anti-slavery writings in the Alton Observer led to his 1837 lynching. It was more or less an open secret around Princeton that his modest farmhouse on the outskirts of town was a station on the so-called "Liberty Line" of the Underground Railroad. The house is now a city-owned museum restored to its period appearance (including the "hidey-holes" where fugitive slaves were concealed) and opened to tours in season. Onsite also is a one-room schoolhouse with exhibits that further delve into the pioneer history of the area.

- 66 Graue Mill and Museum, 3800 York Rd., Oak Brook, ☏ +1 630 655-2090. Tu-Su 10AM-4:30PM, mid Apr-mid Nov. German immigrant Frederick Graue housed fugitive slaves in the basement of his gristmill on Salt Creek, which was a favorite stopover for future President Abraham Lincoln during his travels across the state. Today, the building has been restored to its period appearance and functions as a museum where, among other exhibits, "Graue Mill and the Road to Freedom" elucidates the role played by the mill and the surrounding community in the Underground Railroad. $4.50, children 4-12 $2.

From Chicago (or points across the Wisconsin border such as Racine or Milwaukee), travel onward would be by water across the Great Lakes.

Into the Maritime Provinces[edit]

Another route, less used but still significant, led from New England through New Brunswick to Nova Scotia, mainly from Boston to Halifax. Though the modern-day Maritime Provinces did not become part of Canada until 1867, they were within the British Empire, and thus slavery was illegal there too.

One possible route (following the coast from Philadelphia through Boston to Halifax) would be to head north through New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Maine to reach New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

- 2 Wedgwood Inn, 111 W. Bridge St., New Hope, Pennsylvania, ☏ +1 215 862-2570. Located in Bucks County some 40 mi (64 km) northeast of Philadelphia, New Hope is a town whose importance on the Underground Railroad came thanks to its ferry across the Delaware River, which escaped slaves would use to pass into New Jersey on their northward journey — and this Victorian bed and breakfast was one of the stations where they'd spend the night beforehand. Of course, modern-day travellers sleep in one of eight quaintly-decorated guest rooms, but if you like, your hosts will show you the trapdoor that leads to the subterranean tunnel system where slaves once hid. Standard rooms with fireplace $120-250/night, Jacuzzi suites $200-350/night.

With its densely wooded landscape, abundant population of Quaker abolitionists, and regularly spaced towns, South Jersey was a popular east-coast Underground Railroad stopover. Swedesboro, with a sizable admixture of free black settlers to go along with the Quakers, was a particular hub.

- 67 Mount Zion AME Church, 172 Garwin Rd., Woolwich Township, New Jersey (1.5 miles/2.4 km northeast of Swedesboro via Kings Hwy.). Services Su 10:30AM. Founded by a congregation of free black settlers and still an active church today, Mount Zion was a reliable safe haven for fugitive slaves making their way from Virginia and Maryland via Philadelphia, providing them with shelter, supplies, and guidance as they continued north. Stop into this handsome 1834 clapboard church and you'll see a trapdoor in the floor of the vestibule leading to a crawl space where slaves hid.

New York City occupied a mixed role in the history of American slavery: while New York was a free state, many in the city's financial community had dealings with the southern states and Tammany Hall, the far-right political machine that effectively controlled the city Democratic Party, was notoriously sympathetic to slaveholding interests. It was a different story in what are now the outer boroughs, which were home to a thriving free black population and many churches and religious groups that held strong abolitionist beliefs.

- 68 [dead link] 227 Abolitionist Place, 227 Duffield St, Brooklyn, New York. In the early 19th century, Thomas and Harriet Truesdell were among the foremost members of Brooklyn's abolitionist community, and their Duffield Street residence was a station on the Underground Railroad. The house is no longer extant, but residents of the brick rowhouse that stands on the site today discovered the trapdoors and tunnels in the basement in time to prevent the building from being demolished for a massive redevelopment project. The building is now owned by a neighborhood not-for-profit with hopes of turning it into a museum and heritage center focusing on New York City's contribution to abolitionism and the Underground Railroad; in the meantime, it plays host to a range of educational events and programs.

New England[edit]

- 69 Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 77 Forest St., Hartford, Connecticut, ☏ +1 860 522-9258. The author of the famous antislavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin lived in this delightful Gothic-style cottage in Hartford (right next door to Mark Twain!) from 1873 until her death in 1896. The house is now a museum that not only preserves its historic interior as it appeared during Stowe's lifetime, but also offers an interactive, "non-traditional museum experience" that allows visitors to really dig deep and discuss the issues that inspired and informed her work, including women's rights, immigration, criminal justice reform, and — of course — abolitionism. There's also a research library covering topics related to 19th-century literature, arts, and social history.

- 70 Greenmanville Historic District, 75 Greenmanville Ave., Stonington, Connecticut (At the Mystic Seaport Museum), ☏ +1 860 572-5315. Daily 9AM-5PM. The Greenman brothers — George, Clark, and Thomas — came in 1837 from Rhode Island to a site at the mouth of the Mystic River where they built a shipyard, and in due time a buzzing industrial village had coalesced around it. Staunch abolitionists, the Greenmans operated a station on the Underground Railroad and supported a local Seventh-Day Baptist church (c. 1851) which denounced slavery and regularly hosted speakers who supported abolitionism and women’s rights. Today, the grounds of the Mystic Seaport Museum include ten of the original buildings of the Greenmanville settlement, including the former textile mill, the church, and the Thomas Greenman House. Exhibits cover the history of the settlement and its importance to the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement. Museum admission $28.95, seniors $26.95, children $19.95.

- 71 Pawtuxet Village, between Warwick and Cranston, Rhode Island. This historically preserved neighborhood represents the center of one of the oldest villages in New England, dating back to 1638. Flash forward a couple of centuries and it was a prominent stop on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves. Walking tours of the village are available.

- 72 Jackson Homestead and Museum, 527 Washington St., Newton, Massachusetts, ☏ +1 617 796-1450. W & Su 11AM-5PM, and by appointment. This Federal-style farmhouse was built in 1809 as the home of Timothy Jackson, a Revolutionary War veteran, factory owner, state legislator, and abolitionist who operated an Underground Railroad station in it. Deeded to the City of Newton by one of his descendants, it's now a local history museum with exhibits on the local abolitionist community as well as paintings, photographs, historic artifacts, and other curiosities. $6, seniors and children 6-12 $5, students with ID $2.

Boston was a major seaport and an abolitionist stronghold. Some freedom seekers arrived overland, others as stowaways aboard coastal trading vessels from the South. The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841-1861), an abolitionist organization founded by the city's free black population to protect their people from abduction into slavery, spread the word when slave catchers came to town. They worked closely with Underground Railroad conductors to provide freedom seekers with transportation, shelter, medical attention and legal counsel. Hundreds of escapees stayed a short time before moving on to Canada, England or other British territories.

The National Park Service offers a ranger-led 1.6 mi (2.6 km) Boston Black Heritage Trail tour through Boston's Beacon Hill district, near the Massachusetts State House and Boston Common. Several old houses in this district were stations on the line, but are not open to the public.

A museum is open in a former meeting house and school:

- 73 Museum of African-American History, 46 Joy St., Boston, Massachusetts, ☏ +1 617 725-0022. M-Sa 10AM-4PM. The African Meeting House (a church built in 1806) and Abiel Smith School (the nation's oldest public school for black children, founded 1835) have been restored to the 1855 era for use as a museum and event space with exhibit galleries, education programs, caterers' kitchen and museum store.

Once in Boston, most escaped slaves boarded ships headed directly to Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. A few crossed Vermont or New Hampshire into Lower Canada, eventually reaching Montreal...

- 74 Rokeby Museum, 4334 US Route 7, Ferrisburgh, Vermont (11 miles/18 km south of Shelburne), ☏ +1 802 877-3406. 10AM-5PM, mid-May to late Oct; house only open by scheduled guided tour. Rowland T. Robinson, a Quaker and ardent abolitionist, openly sheltered escaped slaves on his family's sheep farm in the quiet town of Ferrisburgh. Now a museum complex, visitors can tour nine historic farm buildings furnished in period style and full of interpretive exhibits covering Vermont's contribution to the Underground Railroad effort, or walk a network of hiking trails that cover more than 50 acres (20 ha) of the property. $10, seniors $9, students $8.

...while others continued to follow the coastal routes overland into Maine.

- 75 Abyssinian Meeting House, 75 Newbury St., Portland, Maine, ☏ +1 207 828-4995. Maine's oldest African-American church was erected in 1831 by a community of free blacks and headed up for many years by Reverend Amos Noé Freeman (1810-93), a known Underground Railroad agent who hosted and organized anti-slavery speakers, Negro conventions, and testimonies from runaway slaves. But by 1998, when the building was purchased from the city by a consortium of community leaders, it had fallen into disrepair. The Committee to Restore the Abyssinian plans to convert the former church to a museum dedicated to tracing the story of Maine's African-American community, and also hosts a variety of events, classes, and performances at a variety of venues around Portland.

- 76 Chamberlain Freedom Park, Corner of State and N. Main Sts., Brewer, Maine (Directly across the river from Bangor via the State Street bridge). In his day, John Holyoke — shipping magnate, factory owner, abolitionist — was one of the wealthiest citizens in the city of Brewer, Maine. When his former home was demolished in 1995 as part of a road widening project, a hand-stitched "slave-style shirt" was found tucked in the eaves of the attic along with a stone-lined tunnel in the basement leading to the bank of the Penobscot River, finally confirming the local rumors that claimed he was an Underground Railroad stationmaster. Today, there's a small park on the site, the only official Underground Railroad memorial in the state of Maine, that's centered on a statue entitled North to Freedom: a sculpted figure of an escaped slave hoisting himself out of the preserved tunnel entrance. Nearby is a statue of local Civil War hero Col. Joshua Chamberlain, for whom the park is named.

- 77 Maple Grove Friends Church, Route 1A near Up Country Rd., Fort Fairfield, Maine (9 miles/14.5 km east of Presque Isle via Route 163). 2 mi (3.2 km) from the border, this historic Quaker church was the last stop for many escaped slaves headed for freedom in New Brunswick, where a few African-Canadian communities had gathered in the Saint John River Valley. Historical renovations in 1995 revealed a hiding place concealed beneath a raised platform in the main meeting room. The building was rededicated as a house of worship in 2000 and still holds occasional services.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia[edit]

Once across the border, a few black families settled in places like Upper Kent along the Saint John River in New Brunswick. Many more continued onward to Nova Scotia, then a separate British colony but now part of Canada's Maritime Provinces.

- 3 Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom, Glenburn Rd., Carlingford, New Brunswick (7.2 km/4.5 miles west of Perth-Andover via Route 190). first Sa in Oct. After successfully crossing the border into New Brunswick, the first order of business for many escaped slaves on this route was to seek out the home of Sgt. William Tomlinson, a British-born lumberjack and farmer who was well known for welcoming slaves who came through this area. Every year, the fugitives' cross-border trek to Tomlinson Lake is retraced with a 2.5 km (1.6 mi) family-friendly, all-ages-and-skill-levels "hike to freedom" in the midst of the beautiful autumn foliage the region boasts. Gather at the well-signed trailhead on Glenburn Road, and at the end of the line you can sit down to a hearty traditional meal, peruse the exhibits at an Underground Railroad pop-up museum, or do some more hiking on a series of nature trails around the lake. There's even a contest for the best 1850s-period costumes. Free.

- 78 King's Landing, 5804 Route 102, Prince William, New Brunswick (40 km/25 miles west of downtown Fredericton via the Trans-Canada Highway), ☏ +1 506 363-4999. Daily 10AM-5PM, early June-mid Oct. Set up as a pioneer village, this living-history museum is devoted primarily to United Empire Loyalist communities in 19th century New Brunswick. However, one building, the Gordon House, is a replica of a house built by manumitted slave James Gordon in nearby Fredericton and contains exhibits relative to the Underground Railroad and the African-Canadian experience, including old runaway slave ads and quilts containing secret messages for fugitives. Onsite also is a restaurant, pub and Peddler's Market. $18, seniors $16, youth (6-15) $12.40.

Halifax, the final destination of most fugitive slaves passing out of Boston, still has a substantial mostly-black district populated by descendants of Underground Railroad passengers.

- 79 Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, 10 Cherry Brook Rd., Dartmouth, Nova Scotia (20 km/12 miles east of downtown Halifax via Highway 111 and Trunk 7), ☏ +1 902-434-6223, toll-free: +1-800-465-0767, fax: +1 902-434-2306. M-F 10AM-4PM, also Sa noon-3PM Jun-Sep. Situated in the midst of one of Metro Halifax's largest African-Canadian neighbourhoods, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia is a museum and cultural centre that traces the history of the Black Nova Scotian community not only during the Underground Railroad era, but before (exhibits tell the story of Black Loyalist settlers and locally-held slaves prior to the Emancipation Act of 1833) and afterward (the African-Canadian contribution to World War I and the destruction of Africville) as well. $6.

- 80 Africville Museum, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, Nova Scotia, ☏ +1 902-455-6558, fax: +1 902-455-6461. Tu-Sa 10AM-4PM. Africville was an African-Canadian neighbourhood that stood on the shores of Bedford Basin from the 1860s; it was condemned and destroyed a century later for bridge and industrial development. This museum, situated on the east side of Seaview Memorial Park in a replica of Africville’s Seaview United Baptist Church, was established as part of the city government's belated apology and restitution to Halifax's black community, and tells its story through historic artifacts, photographs, and interpretive displays that inspire the visitor to consider the corrosive effects of racism on society and to recognize the strength that comes through diversity. An "Africville Reunion" is held in the park each July. $5.75, students and seniors $4.75, children under 5 free.

Stay safe[edit]

Then[edit]

With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act by Congress in 1850, slaves who had escaped to the northern states were in immediate danger of being forcibly abducted and brought back to southern slavery. Slave catchers from the south operated openly in the northern states, where their brutality quickly alienated the locals. Federal officials were also best carefully avoided, as the influence of plantation owners from the then more populous South was powerful in Washington at the time.

Slaves therefore had to lie low during the day — hiding, sleeping or pretending to be working for local masters — and move north by night. The further north, the longer and colder those winter nights became. The danger of encountering U.S. federal marshals would end once the Canadian border had been crossed, but the passengers of the Underground Railroad would need to remain in Canada (and keep a watchful eye for slave catchers crossing the border in violation of Canadian law) until slavery was ended via the American Civil War of the 1860s.

Even after the end of slavery, racial struggles would continue for at least another century, and "travelling while black" continued to be something of a dangerous proposition. The Negro Motorist Green Book, which listed businesses safe for African-American travellers (nominally) nationwide, would remain in print in New York City from 1936 to 1966; nonetheless, in more than a few "sundown towns" there was nowhere for a traveller of color to stay for the night.

Now[edit]

Today, the slave catchers are gone and the federal authorities now stand against various forms of racial segregation in interstate commerce. While an ordinary degree of caution remains advisable on this journey, the primary modern risk is crime when traveling through major cities, not slavery or segregation.

Go next[edit]

Then[edit]

Only a small minority of successful escapees stayed in Canada for the long haul. Despite the fact that slavery was illegal there, racism and nativism were as much a problem as anywhere else. As time went on and more and more escaped slaves poured across the border, they began to wear out their welcome among white Canadians. The refugees usually arrived with only the clothes on their backs, unprepared for the harsh Canadian winters, and lived a destitute existence isolated from their new neighbors. In time, some African-Canadians prospered in farming or business and ended up staying behind in their new home, but at the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, many former fugitives jumped at the chance to join the Union army and play a role in the liberation of the compatriots they'd left behind in the South. Even Harriet Tubman herself left her home in St. Catharines to enlist as a cook, medic, and scout. Others simply drifted back to the U.S. because they were sick of living in an unfamiliar place far from their friends and loved ones.

Now[edit]

- The end of the Ohio Line coincides with the beginning of the Windsor-Quebec corridor, the most populous and heavily urbanized area of Canada. Head east along Highway 401 toward the majestic Niagara Falls, cosmopolitan Toronto, the lovely Thousand Islands, and the French-flavoured Montreal and Quebec City.

- If you've gone the East Coast route, you'd be remiss not to explore the Atlantic Provinces, where whale-watching, gorgeous seaside scenery, tasty seafood, and Celtic cultural influences abound.

See also[edit]

- Atlantic slave trade — the insidious process by which slaves got from Africa to North America in the first place

- Early United States history — a tangled saga of which the slavery question was only one thread

- From Plymouth to Hampton Roads