Out of the frying pan and into the fire, that might have been the feeling of a typical Mexican in the post-independence era of the mid-to-late 19th century into the first few years of the 20th century. To say it was a tumultuous time would be a severe understatement. Wars, insurrection, coups, foreign invasions and an authoritarian dictatorship were what lay in store for the century following Mexico's hopeful advance into independence. This article presents a very brief, perhaps opinionated, and hopefully entertaining look at the century between Mexico's independence from Spain and it's civil war, the Mexican Revolution, which would have an enduring impact on Mexico's future. It covers the 90-year period from 1820 to 1910.

| Mexico historical travel topics: Mesoamerica → Colonial Mexico → Mexican War of Independence → Post-Independence Mexico → Mexican Revolution → Modern Mexico |

Monarchy and Republic (1820-1829)

Once Mexico gained independence, things were shaky for the first decade. The government was to be a constitutional monarchy, but an appropriate monarch couldn't be found and so Agustin Iturbide was named the first Emperor of Mexico. The wealthy land owners were never behind the idea of constitutional monarchy. Neither were the military or the church. They preferred a republican form of government. When Iturbide attempted to relieve Santa Anna of his military command, Santa Anna called for an end to the Empire and had the support of the military. Iturbide saw the writing on the wall and stepped down as Emperor, allowing congress to write a new constitution of 1824 that called for a republican form of government with an elected president and that set up Mexico's system of states, similar to the model of the United States. The constitution was deeply flawed with built-in abuses allowed for the church and the military. The first president was General Guadalupe Victoria. The second was General Vicente Guerrero.

Destinations

- 1 Palace of Iturbide, Francisco Madero 17, Mexico City/Centro. Former official residence of Agustin I, Emperor of Mexico between 1821-1823.

Santa Anna (1829-1854)

Adding to the turmoil of the 1820s, Spain didn't recognize Mexico's independence and made a couple of weak attempts to regain its colony, including a naval attack on the port of Tampico in 1829, which was defended by General Santa Anna. His victory over the Spanish would cement his reputation and allow him to dominate Mexican politics for the next 25 years. They weren't quiet years though, because the constitution of 1824 failed to address systemic abuses by the church and the military, allowed advantages to a rich minority to continue, and disenfranchised the country's majority. As a result, unrest would continue throughout the century.

Yucatan Revolution

In 1835, land owners and Mayan indigenous groups instigated a rebellion against the Mexican government in the Yucatán. Santa Anna led his army to successfully put down the biggest fires of the rebellion, but the rebellion (referred to as the Caste War) didn't really end because the underlying problems of land appropriation from indigenous Mayan were never addressed. The Yucatan would continue to be a troublesome region for all succeeding presidents throughout the 19th century until the Mexican Revolution finally did address indigenous land rights.

Unfortunately for Santa Anna, trouble was also brewing in the northern state of Coahuila y Tejas.

Texas Revolution

In 1835–1836, Texas land owners and a rag-tag bunch of Anglo rabble rousers and land grabbers instigated an insurrection against the Mexican government. They would eventually succeed in their fight and secede from Mexico to form an independent state (eventually to be annexed by the United States). This was the first of a series of severe losses of Mexican territory and a severe blow to Santa Anna's reputation.

Mexican-American War

In 1845, the United States government yearned to steal Mexican territory. The U.S. government provoked Mexico in 1845 by annexing the independent territory of Texas and then reneging on the treaty with Mexico by falsely claiming that the southern border of Texas was the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo) instead of the Rio Nueces, as agreed in the treaty. In 1846, the U.S. expanded the conflict by pushing west into Mexico's northwest territory, which includes the modern-day U.S. states of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and California. Meanwhile, U.S. president Taft ordered the army and navy to attack the port of Veracruz and to move inland to attack the capital. General Winfield Scott commanded 12,000 men who defeated the defenders at Veracruz and marched on Mexico City. The last major battle in the conflict was an attack on the Mexican Military Academy, then located in Chapultepec Castle high atop a hill in the center of the city. The battle was a defeat for the Mexicans, but it is a treasured historical story of bravery and patriotism as six of the young academy cadets who were defending the site chose to die rather than surrender to the invaders. They are known throughout Mexico as the Niños Héroes. The war ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo which called for Mexico to cede its northern territories to the United States. The land grab met with acclaim in many parts of the U.S., though political scholars believe it might have fueled emotions that started the U.S. Civil War because there was dissent about whether the newly stolen territories should be free states or slave states. In Mexico, the humiliating defeat spelled writing on the wall for Santa Anna's inevitable political defeat.

Destinations

- 2 Alamo, San Antonio, Texas. Insurrectionists barricaded themselves inside the Mision San Antonio de Valero. Santa Anna's army laid siege to the mission, eventually killing the traitors, but not without sustaining heavy losses themselves.

- 3 San Jacinto Battleground, Houston, Texas. Santa Anna's army was defeated by an inferior force led by Sam Houston, leading to Santa Anna's surrender and the end of the Texas Revolution.

- 4 Monument to the Niños Héroes, Av. Juventud Heroica, Mexico City/Chapultepec. At the entrance to Chapultepec Park is a semicircle with six marble columns. This is a revered patriotic memorial to the six heroic cadets who were defending Chapultepec against foreign aggression and chose death over capitulation.

The Reform Era of Benito Juarez (1855-1876)

In the mid-19th century, Mexico desperately cried out for a more just and equal government while conservative interests of the wealthy land owners, army leadership, and the Catholic church battled to keep their privileged positions of power. Reform was the force of the times though, and progressive ideas and reform politicians usually ended up carrying the day as special privileges of the conservative minority were steadily whittled away in the Constitucion de 1857 (there sure were a lot of constitutions and "plans").

Ignacio Comonfort was the first president elected in the post-Santa Anna period. Comonfort was a moderate who was not solidly conservatirve, nor gung-ho liberal. As a result, he ended up satisfying neither end of the political spectrum though he did put in place policies that pushed Mexican government more firmly to the left.

Benito Juarez Presidency (1858-1872)

Benito Juarez was Mexico's first indigenous president. He was from a poor Zapotec family in the state of Oaxaca (where he continues to be revered as one of Mexico's greatest presidents). Although very popular with near-unanimous acclaim of poorer communities, especially among the indigenous and mestizos, he was reviled by conservative insurrectionists who fought to preserve inequality and injustice. This would manifest itself through bullets flying in the Reform War over differences in philosophy and privilege, and even when the country clearly had no appetite to support the greedy, selfish conservatives, they would "double down" by betraying their country and supporting a French invasion force under Napoleon III.

French Intervention (1862-1867)

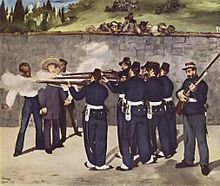

With the United States embroiled in Civil War, France saw its opportunity to meddle in Mexico's affairs and maybe even steal some of its territory, since intervention had worked out that way for the Americans. In 1861 France demanded that the Juarez government pay reparations for some trumped up imaginary offense. Juarez told Napoleon to stick that demand where it belonged. In 1862, France sent troops to attack Veracruz, then to march on Puebla where on May 5, 1862, they were opposed by General Zaragoza who held the twin forts of Guadalupe and Loreto. The French were handed an unexpected defeat, though they eventually did manage to capture Puebla. The French army marched on Mexico City and with the support of Benito Juarez's enemies in the conservative coalition, installed an illegitimate shadow government under Emperor Maximilian I, a Hapsburg prince imported to Mexico by Napoleon as his puppet. Unexpectedly, Maximilian turned out to not be quite the sphincter that Napoleon or the Mexican conservatives thought he would be, he sympathized with the Mexican majority and not only failed to roll back liberal reforms, actually implemented a few of his own. It wouldn't be enough to save his skin though. He was still a puppet monarch of foreign interventionists backed by traitors within Mexico, so a well-deserved execution was to be his fate. That's just what he met when he tried to flee to Queretaro. By that time, the U.S. Civil War had ended and the U.S. had begun sending supplies to support Benito Juarez's presidency. After all, U.S. president Monroe had warned off Europeans about meddling anywhere in the Americas, and France's meddling was certainly not to be ignored. The French went back to France with their tails tucked firmly between their legs.

Destinations

- 5 Museo Casa de Juarez (Juarez Home), Calle Manuel García Vigil 609 Oaxaca. Small museum in a house where the former president was raised. Lacks historical insight to Juarez's philosophy or political career and definitely packs no punch as far as explaining his impact on Mexico's society and future. An interesting diversion if you're visiting Oaxaca (where everything, including the city itself, has Juarez's name attached to it).

- 6 Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones (National Museum of Interventions, Ex-Monastery of Churubusco), 20 de Agosto, San Diego Churubusco, Mexico City/Coyoacan. Historical museum that documents foreign incursions into Mexico during the 19th century with galleries dedicated to American incursions during the Mexican-American War and French incursions during the presidency of Benito Juarez. Many period pieces and documents in several galleries of a historic monastery where fighting actually occurred during one of the incursions.

- 7 Cerro de la Camapanas, Queretaro. Site where Emperor Maximilian I was executed by firing squad following his trial and conviction for treasonous acts. The site is also home to the Monument to Benito Juarez, a fitting symbol of the triumph of democracy over foreign interference.

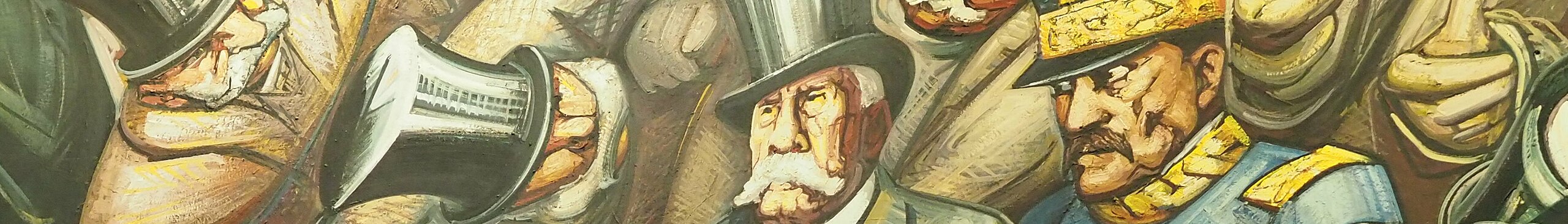

Porfiriato (1876-1910)

Porfirio Díaz was a former war hero who sided with the liberals and he had popular support on his side, but he forgot about the people as he found gifts from foreign corporations too easy to accept and favors too easy to dispense. He became a dictator who rigged elections and became despised by the people. When he lost the election of 1910, he refused to step down, until he was forced into exile and died an ignoble death.

Retrospective on the 19th century

Quick recap: There weren't many Mexican heroes of the 19th century. Benito Juarez is the only major political figure who history views as a positive force in Mexico. Most of the others were either power-hungry, greedy, stupid, or inept (choose 2 for each villain). As a result, you don't find monuments and museums dedicated to their memories.

The single best place to see exhibits about this period is the National Museum of Mexican History.

Destinations

- 8 National Museum of Mexican History, Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City/Chapultepec. Mexico's primary history museum, with exhibits spanning all time periods. Housed in the historic Chapultepec Castle.