Earthquakes are some of the most serious natural disasters. Fortunately major earthquakes occur, even on a global scale, only a few times a year and hence short-term visitors are very unlikely to end up in one. Nevertheless, if you do end up in one, there is a serious risk to your life and health.

Understand

Minor earthquakes that are hardly noticeable can occur anywhere in the world. The truly disastrous ones occur mostly in these regions:

- the area from Italy to southern China (roughly along the Silk Road), also known as the Alpide belt

- along the Pacific rim (New Zealand, Indonesia, Philippines, Taiwan, Japan, Russian Far East and the west coast of the Americas from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego), also known as the Ring of Fire

- in the Caribbean

These areas are known as convergent tectonic boundaries. In these areas, tectonic plates (that form the crust of the Earth) are pushed towards each other and when they get stuck, stress builds up. When they break free, the sudden release of this stress is experienced as an earthquake.

In places where tectonic plates are moving away from each other (e.g. Iceland) you will encounter other phenomena associated with tectonic boundaries, such as volcanoes, but rarely major earthquakes.

Earthquakes can cause tsunamis, which can wreak havoc thousands of miles away, on the other side of an ocean.

Sometimes, earthquakes can also occur away from tectonic plate boundaries. These are known as intraplate earthquakes. While they are much rarer and usually less intense than the earthquakes that occur at the plate boundaries, they are often more devastating due to the fact that the areas where they occur are often not prepared for them. One of the most devastating examples of an intraplate earthquake is the 1976 Tangshan earthquake in China.

Large earthquakes may destroy buildings and other infrastructure. During a major earthquake, expect windows to shatter, trees to fall and things to be thrown around. However, the danger isn't over once the quake has ended. Buildings that have been damaged by the earthquake can suddenly collapse, and severed gas pipes and power lines can cause fires. Landslides and soil liquefaction can make buildings and other infrastructure move, sink or collapse. In addition to all this, roads, water, electricity (and therefore communication) and other utility lines are often damaged, which makes communication and rescue operations harder. Furthermore, aftershocks may occur and cause further damage.

How earthquakes are measured

Earthquakes are measured using various scales. The magnitude of an earthquake is a single number that represents "how big" the earthquake is. Intensity represents "how much shaking there is", which varies by location; places near the epicenter will have higher intensity than very distant locations.

Richter magnitude scale

The first scale for measuring earthquakes' magnitude was the Richter magnitude scale developed by Charles F. Richter in 1935. Since the 1980s the modern scale for large earthquakes (ones worth reporting in the news, anyway) has been the "moment magnitude scale", but the press and much of the public continue to use the name "Richter scale" even though it's inaccurate. Whatever the name, this is often how the magnitude of an earthquake is reported by governments, aid organisations, and the media.

Note that the Richter magnitude scale is logarithmic, so a M7.0 earthquake has 31.6 times the energy of a M6.0 earthquake, 1000 times the energy of a M5.0 earthquake, and so on.

The scale is measured as so:

- 1.0–1.9: Micro. These earthquakes are tiny in scale and are not often felt by people. There is little movement of the ground. In more earthquake-prone areas these can be a daily occurrence.

- 2.0–3.9: Minor. More likely to be felt by people but rarely cause damage. Some indoor objects may shake.

- 4.0–4.9: Light. Shaking is felt by most people in the area. Can cause minor damage. Some indoor objects may fall over or fall off shelves.

- 5.0–5.9: Moderate. Can damage poorly constructed buildings. May cause minor damage to other buildings. Felt by everyone.

- 6.0–6.9: Strong. More damage occurs, even to well-built buildings. Poorly constructed buildings may topple. There is strong and violent shaking of the ground which can be felt hundreds of kilometres away from the epicentre. In most regions, a tsunami alert is triggered after undersea earthquakes of at least 6.5 in magnitude.

- 7.0–7.9: Major. Widespread damage to most buildings including collapse. Damage and violent shaking can be spread across great distances up to 250km from the epicentre.

- 8.0–9.0+: Great. Widespread and major damage across a large area, possible total destruction. Violent shaking may be felt even in distant areas. There are permanent changes in ground topography. 9.0 was the magnitude of the devastating 2011 earthquake in Tōhoku, Japan, while the most powerful earthquake ever recorded occurred at 9.5 on the scale in Valdivia, Chile in 1960.

Intensity scales

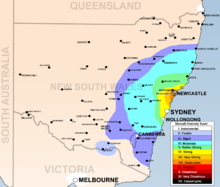

Intensity scales can be used to describe the potential damage in a particular area, and it is possible to have a "contour map" showing how the intensity varied around the epicentre. Different but similar scales are used in different parts of the world.

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale is used in the U.S., Australia and New Zealand. The scale values range from I (Not felt) through IV (Light, felt by many indoors) to VIII (Severe, great damage in poorly built buildings) to a maximum of XII (Extreme, total damage).

The European macroseismic scale is used in Europe. The scale values range from I (Not felt) through IV (Largely Observed) to VIII (Heavily Damaging) to a maximum of XII (Completely Devastating).

The Japan Meteorological Agency seismic intensity scale, also known as the Shindo (震度, "seismic intensity") scale, is used in Japan. The scale values (Shindo number) vary from 0 (Not felt) through 4 (Slight damage to non-earthquake resistant buildings) to 7 (All buildings severely damaged). To make the scale more accurate, 5 and 6 are split into "weak" (弱,jaku) and "strong" (強,kyō), yielding 10 possible values.

Prepare

In general, locals in earthquake-prone areas should know how to act if and when shaking starts. Follow their advice and example.

If you are in an earthquake zone, always keep your travel documents (tickets, passport, etc.), money and important personal belongings in a place where you can easily grab them if you need to escape—though you should not make them so visible that they attract thieves. Keep a pair of shoes near your bed. If an earthquake strikes at night while you're sleeping, you'll want to put shoes on in case there's broken glass.

Also, you may want to survey some ways for getting out in case the front door has collapsed or been blocked by debris or fire. If you stay at a hotel, have a look at the map of emergency exits on the inside of your room door. Emergency exits are usually designed to better evacuate a building in case of fire; however, they may also provide means of escaping a building you fear might collapse due to seismic damage. In the worst-case scenario, you may have to go out of the window and climb down along a downspout or even jump.

Do not put heavy objects in high places, especially above your bed.

Longer stays

If you are going to stay for a longer time in an earthquake-risk area, you may want to prepare an earthquake survival kit. This would include at least:

- 3 to 5 days provisions of food and water (1 gallon (4 L)/person/day), as well as water purification tablets or a portable water filter

- First aid kit, gloves, goggles and a dust mask

- Personal toiletries

- Copies of your important documents (passport, driver's license, insurance papers, etc.) as well as photos of everyone in your party (for helping emergency staff to look for missing persons)

- Emergency contact information on your person, so that authorities can contact your family/friends should you be found

- Cash ($100 at least), in small denominations, preferably local currency or a widely accepted "hard currency"

- Spare batteries, flashlights and a battery-operated radio

In addition, if applicable, you would also want to make your place of abode more earthquake safe (don't keep a lot of loose objects at high places, make sure that shelves are well fastened to walls, etc.) and learn how to switch off gas, electricity and water safely.

If you travel with children, teach them what to do during an earthquake and hold drills.

During an earthquake

Earthquakes are unpredictable—they will often just start without any prior warning signs. However, an earthquake will spread out of the epicenter with a speed of about 7 km/s, and in Japan this has been used to develop an early warning system for earthquakes, giving people further away a warning on TV, radio and to people's cell phones in the affected area a few seconds before the quake will come to them. If you get a warning, you may have barely enough time to extinguish any open fires (gas stoves, candles, etc.), or bring your car to a safe stop if you are driving. The main goal is to take cover immediately!

Do not run during the quake! Standing up, walking and, most of all, running are things that you should avoid as you are likely to fall over and thereby injure yourself. Crawling may be the only way of getting around if you absolutely have to.

A moderate-to-large earthquake usually persists less than a minute (though the exceptionally powerful 2011 Japan earthquake lasted for six minutes), but that is more than long enough to cause damage. Often it will be followed by aftershocks. Do not be complacent after an earthquake seems to be over—get to safety!

If you are indoors

The U.S. FEMA and the New Zealand Civil Defence give the advice "Drop, Cover and Hold" in the case of an earthquake.

Stay indoors. Get down on the floor on your knees and bow down, cover your head and neck, and take cover under a table, desk, or some other sturdy furniture if possible. Hold on to the table to prevent the shaking from separating you from your cover. If possible, shelter under furniture that is next to interior walls, away from windows and tall furniture (such as wardrobes and tall shelves), which could topple over on you. You are far safer if you stay indoors: falling roof tiles, chimney bricks, power lines, and other falling objects outside usually present the deadliest hazards. Doorways in modern buildings are not strong or safe places.

If you are in an elevator, "Drop, Cover and Hold" as you would anywhere else. When the shaking stops, leave the elevator at the nearest available floor if possible, even if the elevator is at a high floor.

If you are in bed, stay there and cover your head and neck with a pillow.

While it is extremely important to extinguish all flames (burners, candles, etc.) immediately if you have time, your immediate danger is from falling objects and toppling furniture.

If you are outdoors

If outdoors, move away from buildings, trees, power lines, or anything that could fall on you. Here, too, it's important to get down as soon as possible, cover yourself and hold on. If you are near a cliff or on a mountain or other elevated natural formation, landslides or avalanches can occur during and after the earthquake.

Stay away from brick walls, glass panels and vending machines, and beware of falling objects: roof tiles from older and traditional buildings are particularly dangerous, as they can drop long after the quake has ended.

If driving, pull over as soon as possible - preferably in an open area away from any structures - and stay in your car until the earthquake is over. If you are on an elevated road such as a bridge or freeway be aware that they may crack or even collapse.

After the earthquake

After the shaking has ended it's safe(r) to move again. Remember that earthquakes are often followed by smaller quakes called aftershocks that can occur minutes, hours or even days or months after the original quake. In the case of an aftershock, follow the same procedures as above.

Try to open up the door or a window as soon as possible, and keep it open by using something such as a doorstop in case it jams.

Get out

If you are indoors, move out. In the worst case, the building has been damaged and may collapse. Move carefully as the light may not be working and there may be broken glass, other debris and live wires around. Small fires should be extinguished, and dangerous chemicals, cleaned up if you can do so safely. If you're staying at a building that you're responsible for (rented vacation home, etc.), check for damaged utilities, and if needed, turn off the gas and electricity from the meter — again, only if you can do it safely and if you know what you're doing.

If the worst has happened and you've been trapped inside a building, avoid lighting matches or kicking up or inhaling dust. Tap on walls or pipes so that rescue crews know that you're there.

In built-up areas, if you move around outside on foot, be aware of potholes on roads and the fact that buildings, bridges, street lights, trees and such may not be standing as firmly as before the quake. If you are moving around in the wilderness, watch out for cracks in the ground. If you are in a mountainous area, rockfalls, landslides or avalanches are also a risk.

If you're next to the coast, you should move inland immediately due to the aforementioned tsunami risk. Remember that tsunami waves are several stories high and in some cases have the power to move several kilometers/miles inland.

If you're in a vehicle, it may be safe to cautiously drive on once the quake has ended. However, you should avoid bridges and similar constructions — the earthquake may have damaged them and made them unstable. Also, the road may also be damaged, or in the worst case, split by the earth's motion and no longer usable.

If you are on a train, it may have automatically stopped once the sensors detected the earthquake. In that case, it's usually best to stay in the train and wait for instructions. If the train has derailed, you should get out and help others get out. Often windows can provide a further mode of escape after being smashed, pulled out or both, depending on the design of the train (there may be instructions on using windows as escape routes, you already read them, didn't you?). Do look before you jump, as the drop from a train window can be substantial, and there may be a powered "third rail" that may cause electrocution if you step on it accidentally.

Help

Help injured people if you can, or at least call for help. Avoid using the phone unless it is an emergency because the phone network will be under a tremendous load handling everyone's emergency calls. If your phone has internet capability, disable that, as this will only cause more stress on the network. Yes, you may want to contact family and friends and tell them what's happened and in what condition you are, but keep in mind than an SMS (text message) will use much less bandwidth and battery than a call or internet connection.

Follow the advice and warnings given by the authorities on radio, TV, the Internet and by rescue crews, police, and military on site. Do help them if explicitly asked, but do not disturb them unnecessarily or otherwise stand in their way staring or taking photos or drive around just for "sightseeing"; let them do their job. Be aware that there is usually a separate organization handling missing people; for example, in the USA, it's the Red Cross.

If you are not a local, it is probably best to try to get out of the affected area if you can — unless you would like to volunteer to help the rescue and relief efforts, in which case you should inquire whether your services would be useful. If you have special skills, such as if you are a doctor, you could help save lives in the aftermath of a disaster. In the case of major disasters such as earthquakes, embassies often want to get in touch with "their" citizens traveling in the affected area to know if they're OK or not.