The Oregon Trail is a 2,200 mi (3,500 km) National Historic Trail across the United States, traditionally beginning in Independence, Missouri and crossing the states of Nebraska, Wyoming, and Idaho before ending near the Pacific coast in Oregon City, Oregon.

An estimated 400,000 settlers used the Oregon Trail or other Emigrant Trail branches to migrate west between the early 1830s and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Today, the memory of the Oregon Trail lives on in books, cinema, and tales of the Old West. Countless more have undertaken the journey – at least vicariously – through one of the earliest (and greatest) educational computer games, The Oregon Trail.

The Oregon National Historic Trail is today's recreation of the trail, maintained by the National Park Service.

Understand

The Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition opened the Northwest for white settlement, and marked the beginning of the Wild West era. The "mountain men" and fur traders who traveled upstream in the early 19th century were few. The first known mountain passes were barely adequate for a horse and rider.

As better routes were found, wagon trails gradually were built westward, laying the groundwork for the Great Migration of 1843. Nearly a thousand settlers crossed the Rocky Mountains in that single year. The Organic Act of the Oregon Territory (1843) granted 640 acres (a square mile, 2.56 km²) of free homestead land per couple in the vast Oregon Territory, which covered what is now Washington state, Oregon, Idaho and parts of Wyoming and Montana. The weakened position of southern states during the American Civil War (1861–1865) gave U.S. federal authorities free rein to promote homesteading and westward expansion. Unimproved homestead land was often free or available for as little as $1.25/acre.

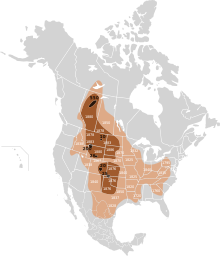

The Emigrant Trail flooded with Oregon-bound homesteaders (1843–1854), who were soon followed by Mormon pioneers (1846–1847) and California gold rush prospectors (1849) heading west. Travelling by wagon, an average group of migrants could complete the Oregon Trail in about six months.

Weather was a major concern; as some mountain passes and river crossings went from treacherous to impossible in winter, expeditions departed in early spring to give time for safe arrival. Hundreds of settlers travelled together as large wagon trains, keeping mutual assistance available in time of need. Migrants traded with other travellers when supplies ran low, abandoning items on the trail when wagons became too heavy for animals to pull. An ox-drawn cart at two miles an hour would need to crawl ten hours a day for more than a hundred days to cover the 2,200-mile trail – and obstacles and delays routinely increased that time. Horses were faster but more expensive, and needed to be fed, while an ox could graze like a cow. Mules had their own stubborn characteristics.

The people and animals often needed to stop for food and water, resting if they were injured or had fallen ill. At night, groups circled the wagons with the livestock in the middle to prevent animals from being stolen or wandering away. On arrival, a successful party could claim contiguous 320-acre parcels for each adult in an entire extended family. Arriving early meant a better chance of claiming prime locations with control over river valleys with water for irrigation.

From 1843–1869, four hundred thousand brave pioneers had heeded the call to "go west, young man", making the arduous trip on trails and infrastructure which had seen few gradual improvements. Some split from the path to colonize Utah or join the California gold rush and some safely reached Oregon's Willamette Valley. Quite a few did not survive the long and arduous journey.

And then, almost overnight, it was over. On May 10, 1869 the Last Spike was driven in tiny Corinne, Utah, thereby joining the Union and Central Pacific railroads; a journey that had taken half a year was abruptly reduced to one week. Where travel by wagon might have cost $200 per person, the train fare was $60 and that with a roof over everybody's heads. It wasn't much of a choice. Before long, the Oregon Trail was a relic of a bygone age, of hardy adventurers and America's first age of westward migration. In movie serials and cheap westerns, the Oregon Trail became a scene for danger and derring-do, full of sinister forces determined to prey upon innocent settlers and tragedy around every bend.

However, the story of the Oregon Trail had a surprising turn ahead. In 1971, a student teacher and amateur programmer named Don Rawitsch created a text-based computer game for his eighth grade history class called The Oregon Trail. On-line gameplay was BASIC and primitive, relying on expensive terminals linked to a distant time-sharing system. As the frontiers of desktop computing advanced, subsequent Oregon Trail versions added graphics, more choices for players to make, and dire consequences for their mistakes.

On The Oregon Trail, students had to name their characters and then subject their creations to mortal peril, from starvation to disease and injuries of every kind. Unlike any other educational game, characters could die; as holding no funeral for a deceased traveller would cause morale of the party to decline, the game allowed players to erect gravestones (usually with profane epitaphs) for subsequent players to find. Players had to choose whether to interact with natives, buy or beg for aid, examine landmarks like Chimney Rock – and, in later versions, hunt for food in a mini-game whose environmentalist message could almost be heard over the howls of bloodthirsty kids. Befuddled teachers found themselves mediating fights between students over whether capsizing a wagon in the Snake River was accidental or a deliberate attempt to lose unwanted members of the party, and who wrote what about whom on a tombstone by the Blue Mountains.

Ported to the Apple ][ in 1979, the Macintosh and IBM PC in 1990, and to game consoles and smartphones in 2011, the game was actually quite good at teaching the history of the Oregon Trail. And, above all else, it was fun.

This itinerary is designed to cover major sights from the real Oregon Trail and the computer game alike. While a full checklist of every wagon rut and historical marker would take months, the goal of this journey is simply to see the vastness of the land, as the original settlers would have experienced it long before steam power and rail travel slashed the duration of a trip around the world from the original three years to a mere eighty days.

Prepare

In the pioneer era, this lengthy journey required careful planning. A farmer often already owned wagons and oxen, but many supplies needed to be purchased and unnecessary items kept off the wagons to keep weight down. Dried, salted or tinned foodstuffs were chosen as they could be preserved for long periods of time. Firearms and ammunition allowed hunting to stretch limited food stocks, if the traveller was skilled in their use. Supplies and skills to repair damaged wagons or treat injured voyagers were essential; opportunities to acquire needed items en route were few and prices became progressively worse as the pioneer ventured further into the hinterland.

Today, the trail can be spread out over a week without much difficulty.

It's a good trip for summer, between June and August. Too early or too late in the year may find some roads impassable due to snow, particularly in Wyoming, and some sights are closed between November and March. Summer will be hot but manageable as long as you carry sunscreen (and your wagon has air conditioning). There will be some long days on the road, so it would be wise to choose a comfortable vehicle and agree upon a code of conduct among the members of your travel party.

You can stock up on provisions at the start of the trail in Independence or Kansas City. While prices have risen since Matt's General Store was selling foodstuffs at $0.20/lb in the game, there are many places to eat meals and buy snacks each day along the trail. With prices and selection largely consistent along the route, there is no need to load hundreds of pounds of supplies into wagons at the trailhead.

Trail-side accommodations of all sorts are available. Major hotel chains can be found off the interstates, while there are motels with local charm (for better or worse) in smaller towns on state routes. There are plenty of campgrounds, which may be closer to the conditions in which early pioneers slept when circling the wagons for the night. Reservations may be necessary during the height of summer in national parks.

The U.S. National Park Service is a good source of information on the Oregon National Historic Trail; their site includes downloadable maps, brochures and state-by-state Auto Tour Route interpretive guides which may be invaluable when trying to follow the historic trail using multiple modern roads and highways.

Get in

The journey begins in Independence (Missouri), which is directly southeast of Kansas City, Missouri.

Kansas City has been a rail transport hub since 1865, having seen a dozen railways come and go over the years. Amtrak's Missouri River Runner reaches KCMO from St. Louis today, with onward connections to Chicago. Well served by highways, Kansas City (MCI IATA) is also the nearest major airport; several rental car firms operate from the Kansas City airport, downtown Kansas City or Independence.

Go

Independence, Missouri

Day 1

Distance: 20 mi (32 km)

Pace: Steady

The National Frontier Trails Museum in 1 Independence is the perfect place to get into an Oregon Trail state of mind:

- 1 National Frontier Trails Museum, 318 W. Pacific, Independence, ☏ +1 816 325-7575, fax: +1 816 325-7579. M-Sa 9AM-4:30PM, Su 12:30-4:30PM, open year-round. Dedicated to several pioneer trails and America's westward migration as a whole, beginning with Lewis & Clark and the early fur trappers, but some fun exhibits challenge you to prepare as a pioneer would. Be sure to gather your travel party for a run at the test wagon. It's surrounded by shelves of weighted sacks of supplies like bullets, beans, and biscuits for you to choose; an alarm goes off if you overload the wagon. This is a great opportunity to argue about who would last how long on the trail without bacon or coffee and really stir up some emotions at the outset. Tales of woe from the trail, artifacts that were abandoned by actual emigrants, and heated debates over the relative merits of mules vs. oxen. $6, $5/seniors, $3/kids.

As the birthplace of U.S. President Harry Truman, Independence boasts a few memorials to its favorite son; as he was born 20 years after the heyday of the Oregon Trail, it's best to try to ignore them.

The 2 1859 Jail and Marshal's Home is period appropriate, in case you'd like to get further into the mindset. It's open April to October.

Having stocked up on supplies, make it an early night, because tomorrow the journey begins in earnest.

Across Nebraska

|

Susan has died of cholera.  Many of the sixty thousand who passed away during the journey rest in poorly-marked or unmarked trailside graves. Susan's lone gravestone near Kenesaw, Nebraska is one exception. A contemporaneous legend claims she died in an 1852 cholera epidemic; her distraught widower travelled to Omaha or St. Joseph to sell their horses and buy an elaborately-carved marble stone, replacing her temporary grave marker. This marker was chipped away by souvenir hunters and is now lost. The 1933 replacement stone references a later legend: this lone grave marks a spot where a settler dug a well to sell water to travellers; the natives killed the settler and poisoned the well; when the husband and wife drank the tainted water, she died but he survived, returning to place the stone in her memory. The Adams County Historical Society is skeptical; no contemporaneous record describes a poisoned well but hastily-buried cholera victims were commonplace and graves often inconspicuous for fear they'd be disturbed by animals or natives. RIP Susan. |

Day 2

Distance: 555 mi (893 km)

Pace: Strenuous

This is a lot of driving for one day, but you might as well cover a lot of ground while spirits are high and the members of your party are still getting along. (The day could be split in half around Kearney if you prefer, but there aren't many trail-related sights in eastern Nebraska, so it will be a flat start to your trip.)

Starting from Independence, take I-435 N to I-29 N toward 2 Omaha. Carry on to 3 Lincoln, where you'll pick up I-80 W. Either Omaha or Lincoln will make a good stop for lunch. This should get you to Fort Kearny in 4 Kearney, Nebraska with enough time to poke around:

- 3 Fort Kearny, 1020 V Rd, Kearney NE, ☏ +1 308 865-5305. State Historical Park and campgrounds open Memorial Day - Labor Day. Established 1848 to protect travellers on the Oregon Trail against attacks by natives, abandoned in 1871. All of the present buildings are reconstructions. For travellers (and players), this was a rare chance to buy supplies, get medical help, or send letters back east. $6/car (additional fees for hunting, boating).

Once you're west of 5 North Platte, you can begin looking for somewhere to spend the night. If you'd like to get off the Interstate, pick up Route 26 just west of 6 Ogallala. The landscape changes very quickly from acres of corn to rolling hills and gorges, lone trees, and distant rock formations. There's an Oregon Trail Trading Post in 7 Lewellen, which is good for fuel, supplies, and taxidermy, and there are some motels as you head northwest, the best of which are in the town of 8 Bridgeport (which also has a decent spread of restaurants and cafés).

Chimney Rock & Fort Laramie

Day 3

Distance: 220 mi (350 km)

Pace: Steady

Get an early start, because this will be a great day. West on Route 26 (which becomes Highway 92) is one of the best sights of the trail.

You have reached Chimney Rock. Would you like to look around?

- 1 Chimney Rock National Historic Site, Chimney Rock Road, Bayerd NE (1.5 mi S of Hwy 92), ☏ +1 308 586-2581. 9AM-5PM daily. This distinctive rock formation was an important waypoint for travellers, standing alone and austere in its surroundings. There is no direct access to the rock, and fences bar visitors from plunging through the sagebrush to get a closer look. There is a $3 admission fee for the visitor center/museum and books on western and trail history are available for purchase, but seeing the rock is free and that's the whole point of being here. $3/adult, kids free.

Down the road is a small 4 historic cemetery that is also worth a stop. Out front is a sign about the rigors of the trail and those who died along the way. There are gravestones erected in the last few years for ancestors who are buried in the vicinity of the cemetery, and older gravestones for people who died some 20-30 years after the end of the trail.

Back on Route 26/Highway 92, head northwest until you reach the town of 9 Scottsbluff. Nearby is the 5 Scotts Bluff National Monument, another important landmark on the trail. Stick with Route 26 when it splits from Highway 92 on the other side of Scottsbluff and head northwest. Like the original emigrants, you are following the Platte River, and will soon cross the state border into Wyoming.

The next major stop is 10 Fort Laramie, with a national historic site near the town of the same name. Turn left from Route 26 to Highway 160 and the fort will be 3 mi (4.8 km) down the road.

- 6 Fort Laramie, 965 Grey Rocks Rd, Ft Laramie, ☏ +1 307-837-2221. This remote frontier outpost predated the Oregon Trail, originating with fur traders. Fort Laramie was situated at the junction of the North Platte and Laramie rivers, with lands well-suited for grazing and camping, making it a natural place to rest and re-supply for travellers. As migration increased, the U.S. Army arrived to take up residence alongside the traders, and then bought the post for its own use.

Today, the fort includes 13 standing buildings, 11 standing ruins, and several buildings where only the foundations remain. Many of the standing buildings have been outfitted with period furnishings, such as the captain's quarters and surgeon's office, while others – like the fort prison – look (and reek) like you're the first person to come across them since the days of the original trail. The visitor center has regular talks about life at the fort, and there are costumed re-enactors to engage (or avoid) if you choose. The spacious grounds are compact but good for a stroll. The picnic grounds are quite nice, and the "Soldiers Bar" has root beer, sarsaparilla, creme soda, and birch beer. Fort Laramie is another highlight of the trail — a sense of the old, weird America, a long way from anywhere. It's open year-round, with extended hours in the summer.

As you continue west, you'll begin to see signs excitedly advertising the presence of "wagon ruts." These are tracks that were worn into stone by the wheels of countless wagons and remain intact today. The best known are the 7 Guernsey Ruts, three miles south of the town of 11 Guernsey (which is about 13 mi (21 km) west of Fort Laramie). They're certainly worth a look to soak up some of the atmosphere the settlers would have experienced. The site is open year-round. Look for the gloriously overheated prose of the Works Progress Administration historic sign nearby.

Route 26 will end at I-25. Head north to 12 Casper, which is a good place to stop for the night. 8 Fort Caspar Museumis a reconstructed 1865 fort at a major crossroads of several trails heading West. The Fort buildings are open April to October, while the museum of both Fort and regional history is open year round.

Independence Rock

Day 4

Distance: 350 mi (560 km)

Pace: Strenuous

Wyoming has done a particularly nice job commemorating the state's ties to the Oregon Trail. There are plenty of historical markers along the way, ranging from little white marble blocks saying 'Oregon Trail' to big, grandiose signs from the 1930s and school lectures from the 1980s. But this is also the state where following the original route takes you furthest afield, so have your navigation and supplies in order before you set out.

From Casper, head southwest on Highway 220 for about 55 mi (89 km), and look for signs for a rest area – with smaller signs referring to a historic site nearby.

You have reached Independence Rock. Would you like to look around?

This is another of the trail's most iconic sights:

- 9 Independence Rock, State Route 220 (south side of route, at the Independence Rock Rest Area), ☏ +1 307 577-5150. Open year round, weather permitting. Seeing Independence Rock was a cause for celebration, if it wasn't too late in the season – popular legend said voyagers had to get here by Independence Day (July 4th) to be on pace to reach Oregon or California before winter. Parties might rest here for a day or two; many carved their names into the rock to commemorate their journey and their ability to keep to a schedule. You can walk about a half-circuit around the rock (the rest is on private ranch land), hunting for signatures or making flailing attempts to climb the smooth surface.

Another trail waypoint, 10 Devil's Gate, is ahead on Highway 220. The "gate" is a gap in a mountain ridge, carved by a river long ago, which opens to a pretty scenic vista.

Highway 220 ends shortly afterward at Highway 287, near the town of 13 Muddy Gap. You can take Highway 287 south to join I-80 W, but an interesting detour lies nearby. (Check your fuel before you commit, because there will be no service stations for a while.) Take 287 northwest past the near-ghost town of Jeffrey City and Sweetwater Station to Highway 28, which you can take southwest. On a hillside is another near-ghost town called 14 Atlantic City, which has some eccentric art and an occasionally open café, and an actual ghost town, 15 South Pass City. Visitors are welcome to wander around this atmospheric mining town, which has several surviving buildings in various states of preservation. The site is overseen by a passionate group of volunteers who will be glad to share information about the history of the area. There's also a surprisingly large souvenir shop. While it can get really hot here, the scenery alone is worth the detour.

Highway 28 meanders south to meet Route 191 at a crossroads in the small town of 16 Farson (which has a gas station). Turn left (south) to meet I-80 W at 17 Rock Springs, where you can find a place to sleep for the night, or...

Wrong trail. Lose 3-4 days.

At this point, the members of your travelling party could probably use some time outside of the car. If hiking or overnight camping sounds appealing, then take a break from the trail and enjoy two of America's most spectacular national parks: 1 Grand Teton National Park and 2 Yellowstone National Park.

Leave I-80 W at Rock Springs to take Route 191 north; or, if you took the South Pass City detour, follow Highway 28 west until the crossroads in Farson, and then turn right to go north on Route 191. The road will join Route 189 and lead directly into 3 Jackson Hole, a tourist town that serves as gateway to the Tetons. (This route winds uphill through the mountains, and while an average driver will be fine in more or less any vehicle, it may be tough for inexperienced drivers, particularly at night, and should not be attempted during winter weather without precaution and experience, assuming the road is even open.)

Continuing north, you'll find Yellowstone, and accommodations should be easy to find in surrounding towns such as 4 West Yellowstone.

Hunting was one of the most popular parts of the computer game, offering an out for players who failed to buy enough food in Independence or at one of the forts along the way. Hence, the opportunity to see Yellowstone's majestic herds – and possibly even bears, from a very safe distance – is practically a must for fans of the game. (Bison top sirloin is on the menu at a few of Yellowstone's restaurants, for anyone who would like to extend the verisimilitude.)

When you're ready to rejoin the trail, take Route 287 north from West Yellowstone, then I-90 W for a short distance to I-15 S.

Snake River Crossing

Day 5

Distance: 290 mi (470 km)

Pace: Strenuous

If you are rejoining the trail via I-15 S, you could make one further stop at 11 Craters of the Moon National Monument, which is well worth the visit off Route 26 (which joins with Routes 20 & 93). A northern spur of the Oregon Trail ran through the Craters of the Moon area; in search of a safe alternative to travel through Shoshone and Bannock Indian lands, a mountain man named Tim Goodale led a party of 1,095 people in 338 wagons through the bumpy lava flows in this area, and soon 18 Goodale's Cutoff overtook the original section of the trail in popularity.

Routes 20/26/93 will diverge, but all three will join I-84 W eventually, and then you're back on the main trail heading west.

If you didn't detour at all, take I-80 W from Rock Springs toward the state border. Fort Bridger, another trading post, is next to the interstate near a tiny hamlet of the same name:

- 12 Fort Bridger (I-80W exit 34), ☏ +1 307 782-3842. May-Sep: museum and historic buildings open daily 9AM-4:30PM; off-season: museum open F-Su 9AM-5PM; grounds open sunrise-sunset year-round. Established by Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez in 1843 as an emigrant supply stop along the Oregon Trail. After a period of Mormon control in the early 1850s, it became a U.S. military outpost in 1858. Museums cover the Oregon Trail, California Trail, Mormon Pioneer Trail, Pony Express Trail, Overland Trail, Cherokee Trail and Lincoln Highway. There are a few restored buildings and a replica trading post. Library, restrooms, picnic area, no camping. $6/car.

At this point the Oregon Trail turns north from Fort Bridger, while the Mormon Trail continues 100 miles westward to the Salt Lake Valley.

Retracing the original trail gets a little complicated here. Take Highway 189 north to Route 30, then travel west on Route 30; when it branches, follow the route north toward 19 Cokeville instead of over the border into Utah. Route 30 will continue into Idaho through 20 Montpelier and 21 Soda Springs. Continue on Route 30 until it merges with I-15 N in 22 McCammon, then stick with Route 30 through 23 Pocatello to meet up with I-86 W, which will eventually become I-84 W.

This section of the trail follows the Snake River through a long, hot stretch of Idaho. Unlike the original settlers, you will not need to make any special effort to cross the Snake River. Unfortunately, few sights of note remain. You'll pass by the city of 24 Fort Hall, which was named for another trading post; the actual fort and its namesake successor are long gone, though, leaving just a replica at Pocatello.

About 10 mi (16 km) west of 25 American Falls, 2 Massacre Rocks State Park shows why voyagers wanted to avoid the Shoshone and Bannock tribes. Ten emigrants were killed here in 1862, just east of the park. Today, the park offers campgrounds, access to the Snake River, and some wagon ruts. Look for 13 Register Rock, a boulder where travellers carved their initials. (It's now protected by a shelter and fence.) The park is open year-round.

The Snake River and Raft River split 15 mi (24 km) further southwest; California-bound prospectors part ways here to head southwest to Nevada.

For those continuing to Oregon, the 26 Boise area makes a good place to stop for the night. The 3 Oregon Trail Reserve (E Lake Forest Dr & Idaho Rte 21) includes a mile of the original trail for hiking and sightseeing on 77 acres of city parkland, at a point where wagons crossed the Boise River.

The Dalles

Day 6

Distance: 338 mi (544 km)

Pace: Steady

Crossing the border into Oregon (and pausing for a brief celebration), take I-84 W toward 27 Baker City. You'll soon have your first sight of the Blue Mountains, which travellers knew meant the end of the journey was near; they usually reached this point by late August or September.

- 14 National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center, 22267 Oregon Hwy 86 (5 mi E of Baker City), ☏ +1 541-523-1843. Summer: daily 9AM-6PM; spring and autumn: daily 9AM-4PM; winter: Th-Su 9AM-4PM. A lot of creativity, research, and humor went into the exhibits here; it's jam-packed with odd stories and artifacts, disheveled mannequins voiced by intensely earnest actors, and more. Outside are a few interpretive trails, a circle of covered wagons, and gorgeous views of the Blue Mountains. There are also some wagon ruts. Open year-round, but hours (and accessibility) are limited in the winter. $8, $5 off-season, kids 0-15 free.

As a side trip, the Hells Canyon Scenic Byway ends at Baker City; if you're doing well on time and the weather is favourable, it is well worth a look to soak up more of the scenery.

When you're ready to move on, continue west on I-84, which meets and follows the famous Columbia River from 28 Boardman onward. The Columbia drains into the Pacific Ocean near Astoria; it was the primary inland route for European traders and settlers, and today is popular for both windsurfers and hydroelectric dams. (Hard to say which an Oregon-bound expedition would have found stranger.)

29 The Dalles is a good place to make camp for the night. There are a couple hotels away from town, near the river, which should add to the excitement. Tomorrow...

Oregon!

Day 7

Distance: 93 mi (150 km)

Pace: Steady

It is strongly recommended that you become insufferable in your period-appropriate speech and behavior, and if you have been saving a good Oregon Trail game t-shirt, now is the time to don it. Because the Willamette Valley is at hand.

|

Barlow Toll Road

The vast majority of the Barlow Toll Road is long gone. Much was incorporated into the Mount Hood Highway (Oregon 35 and US 26) or the web of national forest development roads, but a few traces remain. |

An emigrant party would have faced a difficult decision at The Dalles. There was no trail beyond this point, due to 32 Mount Hood. Pioneers had to convert their wagons to rafts and float down the Columbia River, which carried considerable danger, or shell out a whopping $5 or more to travel the eighty-mile Barlow Toll Road. This mountain road was steep and winding, with wagons pulled on ropes along grades of up to 60% at some points.

Today, you may keep your wagon dry and avoid the Barlow Road by driving west along the south shore of the Columbia River on I-84 (US30) through the 4 Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area – a good place for hiking and natural scenery.

With civilization soon surrounding you, I-84 W will join I-205 S.

Take exit 9 into 33 Oregon City where Abernethy Green, George and Anna Abernethy's 640-acre homestead along the Willamette River, formerly represented the end of the Oregon Trail. This encampment and adjacent properties would fill rapidly with wagon loads of poor and exhausted pioneers seeking shelter from their first Oregon winter. Once here, they could resupply in Oregon City, scout possible homestead locations and file claims at the General Land Office. The original site was destroyed by flooding in 1861; by then, travel time along the Oregon Trail had been nearly halved and emigrants no longer needed to winter over. A visitor center now stands in its place:

- 15 End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive & Visitor Information Center, 1726 Washington St, Oregon City (at Abernethy Road), ☏ +1 503 657-9336. M-Sa 9:30AM-5PM, Su 10:30AM-5PM. As close to an official "end" as there is. The steps outside list many of the landmarks that you've passed along the way, giving a great sense of culmination to the journey. Regrettably, the museum is a bit of a dud, lacking the verve of its eastern counterparts. A souvenir shop sells commemorative patches for those proud few who have completed the trail and there's a sign out front that makes a good photo-op.

Congratulations! Award points for every member of your party who survived the trip and any provisions that you have left, including a working vehicle; triple points if you began as a farmer from Illinois. Alas, land claims are no longer free, but the beauty of the Willamette Valley is yours to enjoy.

Respect

This journey crosses native land.

The history of The Oregon Trail tends to be told through the eyes of early settlers on the wagon trains, an individualistic viewpoint focused on whether the voyager successfully reached the end of the trail. American cinema portrayed the Old West as a place of armed conflict between "cowboys and Indians", but these conflicts were rare in the early days. Between 1840-1860, fewer than 400 people on each side had been killed by conflict between colonists and natives while thousands annually died of disease, infighting, accident and misfortune.

The natives were trading partners and their assistance often invaluable.

Native relations soured when imported measles, smallpox, typhus and dysentery started causing the death of entire villages. Buffalo, once plentiful, declined in number and were disappearing from entire regions.

The Massacre Rocks incident of August 9th, 1862 killed ten settlers. In the retaliatory January 1863 16 Bear River Massacre, Col. Patrick Conner (stationed in Salt Lake City) and his California Volunteers marched north to the Bear River to kill 250 to 400 Shoshoni natives.

The educational video game is careful to label raids “riders attack” since they often came from “white bandits” and not Native Americans, but even its approach oversimplifies a complex history. The game includes no native playable characters and no explanation, from an indigenous perspective, of the impact on native communities as hundreds of thousands of migrants carved wagon roads, polluted water supplies along the trail and decimated wildlife through overhunting.

There is one lone native history museum on the trail:

- 17 Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, 47106 Wildhorse Blvd, Pendleton (on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in eastern Oregon), ☏ +1 541 429-7700 (main), +1 541 429-7702 (Kinship Café), +1 541 429-7703 (store), fax: +1 541 429-7716. The only Native American museum along the Oregon Trail, established 1998 as an interpretative center for the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes.

Stay safe

You have dysentery.

- Disease was a constant, debilitating scourge in the Oregon Trail's heyday. Diphtheria and measles were spread by airborne bacteria, while cholera, dysentery and typhoid fever spread through contaminated water or food. Loss of food to spoilage and supplies to theft were hazards. Many died of illness or starvation. Leaky wagons were inadequate shelters from thunderstorms or heavy rains, causing hypothermia. Remaining stranded on the trail in winter could be fatal. Loaded guns were deadly in inexperienced hands. Voyagers were often crushed by the wheels after falling from wagons which overturned easily on rocks and hills. Before the Green, Kansas, North Platte, Snake and Columbia rivers were bridged, a failed river crossing meant losing wagons, animals and supplies. Settlers were at risk of drowning.

Do you want to ford the river or caulk the wagon and float across?

- In a word, no. Don't do this. Early settlers took deadly risks because they had no choice. Today, there's no need to drive ox and mule carts into un-bridged streams and rivers; all roads are now interstates or well-maintained state routes.

- Any modern wagon should be able to manage the journey today, with a few minor precautions:

- Carry a spare tire and watch your fuel gauge. There are some long stretches between fuel stations.

- Mobile phone reception is not guaranteed all the way through Nebraska, Wyoming, and Idaho.

- A good road atlas should suffice for navigation. GPS is valuable if you veer off the route, Donner Party-style.

- All but a few hundred miles of the original trails have been paved over by two-lane roads; some of the original U.S. Highway System, in turn, has been paved over or replaced by Interstate freeways. Non-motorized vehicles may need to take alternate routes at some busy points.

- Take care when wandering through the sagebrush that you don't disturb any critters, such as snakes.

- Do not ford rivers or caulk your car; handle river crossings by use of roads and bridges. And, of course, carry bottled water – do not drink untreated water from streams lest you join the long, mournful list of those who have died of dysentery.

Go next

- Portland is a half hour from Oregon City; enjoy some time outside of the car with some good food, drink & live music.

- Champoeg, 6.6 mi (10.6 km) SE of Newberg on the Willamette River, was the original location of the provisional government that launched the 1843 land rush. The village was destroyed by a December 1861 flood, the site is now a state park.

- Some travelers ended their journey in Astoria on the coast, a good place to relax.

- Heading south, the lovely Crater Lake National Park is about 3½ hours away.

- If you're inclined to embrace urban environs, continue north on I-5 N to Seattle (3 hours) and Vancouver (5½ hours).

- If you're planning to head back east by car and still have some time to spare, it might be worth taking a northern route on I-90 E through Washington, Idaho, Montana, and South Dakota, all of which offer some interesting sights along the way.

See also

- Old West

- Lewis and Clark Trail

- Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail

- Pony Express National Historic Trail

- Ruta del Tránsito in Nicaragua was an alternative (along with Panama) for those with deeper pockets or on the government dime