- For modern-day trade in China, see Shopping in China

The Silk Road (丝绸之路 sī chóu zhī lù), also known as the Silk Route, is not a single road, but a network of historical trade routes across Asia from China to Europe. One poem calls it "The Golden Road to Samarkand".

In 2014, UNESCO added "Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor" to their World Heritage List. This is a 5000-km (about 3300 miles) stretch from Chang'an (now called Xi'an) in central China to the Tianshan mountain range along the border between China and Central Asia. The western end is the region once known as Zhetysu, now divided between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; its main cities are Almaty and Bishkek. This was only the first of several applications for Silk Road routes; several more are being planned but each nation can nominate only one candidate a year so it will take time to get through the whole list.

Another section, "Silk Roads: Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor" through Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, from the Zeravshan Valley to around Merv, was added in 2023.

Many sites along the historic overland routes are already on the UNESCO list. At the two ends, Xi'an and Istanbul are both listed. In between Samarkand, Bukhara, Merv, Tabriz, Damascus and others are on the list. Several of the great ports on the maritime routes are also listed.

Understand

[edit]Caravans have been travelling the Silk Road for over 2000 years; Chinese silk was reaching Rome and Roman glass was reaching China before 100 BCE.

Trade over parts of the route is far older; there was trade between the Indus Valley Civilisation and Ancient Mesopotamia before 2000 BCE (cities like Mohenjo-daro in Sindh and Nineveh in Iraq), jade from Khotan in what is now Xinjiang was reaching central China by around 1500 BCE and the Persian Royal Road connected the Mediterranean port of Sardis to the Persian Gulf ports in the 5th century BCE. Around that time there was extensive trade all across the Persian Empire, which was centred in what is now Iran and in those days included much of the Caucasus, Central Asia and what is now Turkey.

Around 330 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered from Greece to Egypt, where he founded Alexandria, which later became a great trading city, the main depot for goods from the Maritime Silk Road going to the Mediterranean. Then he turned East and conquered the Persian Empire, which then included much of Central Asia, and after that he took much of Pakistan and parts of northern India. His empire fell apart after his death, but trade continued. He founded what is now the city of Khujand in Tajikistan and took Samarkand; both cities later became centres of Silk Road trade.

In the 2nd century BCE, Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty defeated the Xiongnu (a belligerent confederation of nomadic peoples of the steppes, perhaps related to the Huns who later conquered part of Europe) and established Chinese control over parts of Central Asia for the first time. The pacification of the Xiongnu provided the necessary stability for traders to safely traverse the route, resulting in the first Silk Road being established. In this period, envoys from both Alexander's successors and the Chinese court reached Kashgar; this seems to have been the first contact between China and Europeans.

Although it later declined as China descended into war and anarchy with the fall of the Han Dynasty, the route was re-established and expanded under the 7th century reign of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty after he defeated the Eastern Turks and Western Turks, and re-established Chinese control over much of the parts of Central Asia that were previously ruled by the Han Dynasty. However, the route gradually declined following the fall of the Tang Dynasty, and would eventually be shut during the 15th century, when the ruling Ming Dynasty decided to adopt a policy of isolationism.

From Alexander's time until the Russian expansion into Central Asia in the 19th century, there was usually some powerful Empire at the centre of the Silk Road. The region was conquered by outsiders three times – Alexander, the Arabs in the 7th century CE and the Mongols in the 13th. At other times it was ruled by various incarnations of the Persian Empire or by other empires based in Central Asia, and sometimes these empires included various adjacent regions. Whoever was in charge, trade continued.

While Genghis Khan is popularly known as a destructive raider that raped and pillaged his way across Eurasia, the Mongol Empire had a beneficial effect on trade; though they left few great cities, they did leave a lasting mark on both China and Central Asia. By the time of the Great Khan's grandson, Kublai Khan, the Empire covered almost the entire length of the Silk Road from modern Hungary and Turkey to China and Korea. Within the Empire, tariffs were reduced, roads improved, bandits ruthlessly eliminated, and trade and communication encouraged. Europeans, including Marco Polo, visited the Mongol capital in Karakorum and China. Travel between Europe and China was faster and safer than it was for centuries afterwards. This trade gradually declined during the Black Plague – now thought to have spread in part on silk road trade routes – and the slow decay of the Empire, though successor states ruled by descendants of Genghis kept the road open to some degree well afterwards.

One Mongol descendant was Tamerlane who ruled much of Central Asia in the 14th century; his palace in Samarkand, the Registan, is now a World Heritage Site and one of the Silk Road's best-known attractions. He was a conqueror who dreamed of rebuilding Genghis's great empire. Tamerlane invaded India, Syria, Anatolia and the Caucasus and took cities as diverse as Delhi, Damascus and Moscow; he died while en route to attack China. His descendants created the Mughal Empire in what are now India and Pakistan.

Much more than just silk was traded over this route. Trade was restricted to relatively expensive goods – hauling something like rice or lumber over long distances was not economical with medieval transport – but there was quite a variety of those. Porcelain, glass work, fabrics other than silk, other fine craft items, gems, and furs were traded. So were luxury food items, in particular spices. Coffee, originally from Ethiopia, and tea, originally only from China, first reached the rest of the world via these routes. In medieval London or Paris, pepper cost more than its weight in gold.

Carpets were historically a major trade item and even today, countries along this route produce many fine carpets; these are a major export commodity and a fine thing to bring home as souvenirs. If you bargain moderately well, they are considerably cheaper here than in other places. There is a phenomenal range available, with each region and sometimes each village producing its own designs. The most finely-woven rugs are produced in the great weaving centres of Iran and Turkey, but areas such as the Caucasus, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet are also famous for rugs. There is some carpet production almost everywhere from China in the east to Romania and North Africa in the west, and carpet-making is an important industry in both India and Pakistan.

Ideas also travelled this road. Both Islam and Buddhism reached China by this route and some Silk Road areas have important relics of those religions. Important Buddhist sites include the huge statues at Bamiyan, Afghanistan (now destroyed), the ancient city of Taxila in Pakistan, the large cache of manuscripts found at Gilgit in northern Pakistan, and the caves at Dunhuang in Xinjiang. During the Tang Dynasty, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang (玄奘) made a pilgrimage overland from the then Chinese capital Chang'an (modern day Xi'an) to Buddhist sites in what is today India, Pakistan, Nepal and Afghanistan, including the famed Buddhist university at Nalanda. Xuanzang would subsequently return to China with Buddhist scriptures that he collected during his 18-year-long pilgrimage, and dedicated the rest of his life to translating those scriptures. The epic Chinese novel Journey to the West is a famous fictionalised account of Xuanzang's journey, featuring Xuanzang and three mythical companions as the main characters. Mosques and other Islamic architecture are found all across Central Asia, much of South Asia, and the western provinces of China. There are also some in eastern China, perhaps most notably the fine old mosques in the Silk Road ports Guangzhou and Quanzhou.

Other religions also spread this way; Nestorian Christianity (centred in Persia) sent missionaries as far as Korea, and Xi'an has a stele commemorating their arrival there in the 7th century CE. There were Zoroastrians in Quanzhou by 1000 CE and nearby Jinjiang has the world's last surviving Manichean temple. The first Catholic missionaries reached China by sea in the 14th century, landing at Quanzhou. A community of Jews would also settle in Kaifeng by the 10th century.

Various ideas from the East – notably Chinese inventions such as gunpowder, window glass and use of coal as fuel – also reached the Islamic countries and then Europe via the Silk Road. Chess reached the West from Persia ("checkmate" is from shah mat, Persian for "king dies"), though it was likely invented in India. The game would also be brought to East Asia, where it would evolve into unique national variants in China, Korea and Japan.

Marco Polo followed this route, reaching China overland via Khotan and beginning his homeward journey with a ship on the Maritime Silk Road from Quanzhou to Iran. A few decades later the great Berber traveller Ibn Battuta both entered and left China via Quanzhou. Other famous expeditions include those of Xuanzang (see above), William of Rubruck, Gan Yang (a Chinese explorer who made it as far as Parthia and almost discovered the Roman Empire), and Ibn Fadlan (who used the northern parts of the Silk Road to venture into the Volga region).

The overwhelmingly vast amount of traders and travellers on the Silk Road did not travel large portions of it; rather, they travelled from one city to another nearby and back, bringing goods with them. Travelling most of the Silk Road, like in the famous expeditions mentioned above are rare exceptions to the normal trans-Silk-Road transit. Even today, travelling the entirety of any of the Silk Road routes is a Herculean task, and involves a mastery of visa applications, more than a month of constant travel, lots of money, and an ironclad will.

Disruption during Age of Sail

[edit]At the western end of the Silk Road were the city-states of Italy, where the accumulation of wealth and knowledge led to the Italian Renaissance. Domination of the western Middle East and Balkans by the Ottoman Empire, and its poor relations with much of maritime Europe, led to the Ottomans enacting extremely high taxes on Europeans travelling through their lands. In the late 15th century, advances in shipbuilding technology enabled Vasco da Gama to sail south of Cape Bojador (in modern-day Western Sahara) and discover the Cape Route around Africa, which came to replace the overland routes between Europe and Asia and bypass the Ottoman monopoly over the western Silk Road.

Later Magellan found an alternate route, sailing south of South America. Various European powers established colonies along the old Maritime Silk Road, the British in many places, Portugal in Africa, Goa, Timor-Leste, and Macau, and the Dutch in what is now Indonesia, including the fantastically valuable Spice Islands. The Spanish established an important alternate route with extensive trade between their colonies, mainly on galleons from Acapulco to Manila, and on to mainland Asia. Still later the Suez and Panama canals opened up new routes; steamers using the Suez Canal from its opening in 1869 soon replaced the great sailing tea clippers, which used to run from China to Europe via the Cape of Good Hope (the route is still used – nowadays by ships too large for the canal, and for round-the-world sailing), and likewise, the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 allowed ships to travel between both coasts of North America without making the long and hazardous journey around Cape Horn. The old Maritime Silk Road region of the Pearl River Delta still does extensive trade, mostly seaborne.

In the 21st century, China and its neighbours are investing in land infrastructure – especially railways – possibly creating a renaissance for overland transportation between Europe and Asia. Several European cities now see daily or weekly freight trains from China.

Prepare

[edit]- See also: Tips for travel in developing countries

This is not an easy route or one for the novice traveller. Consult a travel medicine specialist about vaccinations and about medicine to take along.

If you are doing the full route, bring phrasebooks for at least Chinese, Russian, Arabic and Persian. Also note that large portions of the overland routes go through Turkic-majority countries, so knowledge of any of the Turkic languages (Turkish, Uzbek, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Azeri, Turkmen, Tatar, etc.) will also help.

Parts of this route may be difficult or impassable in winter, and various borders may sometimes be closed for political reasons. For most countries on this route, travellers with most passports will require visas obtained in advance. Planning ahead may be needed to get these since some of the smaller nations have few embassies. For example, Turkmenistan does not have an embassy in Ottawa so a Canadian might need to deal with the embassy in Washington, London, Beijing or Moscow to get a visa. Check country listings for details. That being said, each Central Asian country has an embassy in each of the other Central Asian countries, so some travellers will apply for visas in a neighbouring country and wait it out.

Almost anyone travelling this route will want to at least take a look at the fine carpets that are traditionally traded at many places, and perhaps buy some of them. Even on a tight budget, one might want to pick up some of the common smaller items such as woven saddlebags or purses and boots decorated with carpet. Reading a book or two on carpets before setting out is a fine idea; among the most useful writers is a California doctor and carpet collector named Murray Eiland. If you do buy any carpets, be aware of any export restrictions of the country in which you purchased the carpet. For example, Turkmen carpets are some of the highest-valued carpets in the world, but the Turkmen government charges taxes of 115 manat per square meter and a 400 manat psm tax for large carpets, and you're required to obtain a permission of export to take it out of the country.

Some parts of the route are arguably less safe now than they were a few centuries ago. Before heading out, read up on the security situation, and carefully consider whether some countries or regions within countries shouldn't be bypassed entirely. A starting point is our #Stay safe section below.

Get in

[edit]|

21st century Silk Route

In 2013, China announced the Belt and Road Initiative to revamp the historical Silk Road route in order to increase its economic collaboration by creating links with foreign markets. The proposed route is being said to stretch into South Asia, the Middle East, Central Asia and Europe and will surely improve the transportation infrastructure between the regions in the coming years, even though the focus (for now) lies in moving goods not people. As part of this project, Chinese freight trains run regularly between Chinese and European cities, but they operate by loading containers from one train to another at break of gauge points, not as one physical train doing the entire route. |

Many travellers today follow all or part of this ancient path by train, bus and private car. Some Wikivoyage itineraries partly follow the Silk Road.

- Istanbul to New Delhi over land

- On the trail of Marco Polo

- Voyages of Ibn Battuta

- Voyages of Zheng He

- Moscow to Urumqi

You could start a Silk Road journey from anywhere in Europe or China, but the obvious jumping-off spots are the two ends of the historic road – Chang'an, which is now called Xi'an, and Constantinople, now Istanbul.

From either end, the first part of the route can be done by train; China has a good rail system which goes to Kashgar and to Urumqi where there are connections to Almaty. From Russia, there is good rail service to many places in Central Asia. The Trans-Asia Express runs from Istanbul to Tehran. From Tehran there are trains east to Mashad and from there north to Turkmenistan, and also southeast to Zahedan and then Quetta in Pakistan. Going east from Quetta, the Pakistani rail system is quite good, but the Zahedan-Quetta train runs only twice a month and, as of mid-2014, the area around Quetta is considered quite dangerous.

To explore just the central part of the road in Central Asia, it would be easiest to fly into a city in that area with good air connections – Tashkent, Almaty or even Urumqi. One could also get into the area on several rail routes branching off from the Trans-Siberian Railway, though the main line is north of the major Silk Road routes.

Overland routes

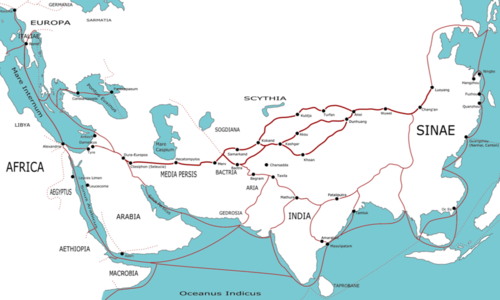

[edit]There were multiple interlinked routes. The map shows the main route from Xi'an to Damascus in yellow with some extensions in green.

Xi'an to Dunhuang (Hexi corridor)

[edit]The main caravan route from China to the West

- started in the capital Chang'an, what we know today as the great city of Xi'an

- headed west past the gorges of Baoji, along the Corn Flake Mountain of Tianshui to Lanzhou on the banks of the Yellow River.

- northwest along the Hexi Corridor to the Han dynasty garrison towns of Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan

- to Jiayuguan, the western terminus of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall, shown as a dotted blue line on the map

- to Guazhou, a region dotted with ancient ruins, including the World Heritage-listed Suoyang City ruins

- to Dunhuang, the 'Blazing Beacon' of Chinese civilization in the western regions. The Jade Gate just outside of Dunhuang delimited the Chinese realm from the semi-independent city states of the Tarim Basin.

There were related routes within China; green links on the map show connections from Xi'an north to Beijing and east to Suzhou and Hangzhou.

Around the desert (Tarim Basin)

[edit]

Beyond Dunhuang the main route splits to go around the Taklimakan Desert.

- Northern route: Dunhuang, Hami, Turfan, Korla, Kashgar

- Southern route: Dunhuang, Cherchen, Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar

- (also called the jade route because Khotan is famous for jade)

The routes above run along the edges of the desert; there are several alternate routes that involve starting on one of the above, then cutting across the center of the desert (e.g. Cherchen to Korla) to finish on the other.

The routes rejoin at Kashgar. Today, Kashgar is China's westernmost city; at other times it has been the capital of an independent kingdom, part of the Mongol Empire, or part of various other Central Asian empires. Today, the majority of its population are Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim ethnic group that is more culturally similar to Central Asians than to the Han Chinese. The city is regarded by most Chinese to be the main centre of Uyghur culture, and is a popular domestic tourism destination. It has a distinctive Central Asian flair.

Central Asia (Transoxiana)

[edit]

After Kashgar, the main route goes:

- northwest over Torugart or Irkeshtam pass into Central Asia

- a secondary route crosses into Tajikistan and goes along the Pamir Highway to Dushanbe before meeting up at Samarkand

- along the Ferghana Valley, through Ferghana, Kokand and Khujand

- on toward Samarkand and Bokhara

- southwest through Turkmenistan, often via Merv, and into Iran, then known as Persia

Middle East

[edit]From Iran, the route goes west from Mashad

Beyond Tehran, the route splits between the southern route through Mesopotamia (mainly today's Iraq and Syria) and the northern route through Anatolia (today's Turkey)

- Southern route: Hamedan (Ecbatana), Baghdad (Seleucia/Ctesiphon), Palmyra, Damascus and all over the south eastern Mediterranean: Tyre, Alexandria

- Northern route: Tabriz, Constantinople all over the north eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea coast: Antioch, Bursa (Cius), Trabzon, Gaziantep (Doliche)

Alternatives

[edit]There were also alternate routes — for example:

- take the steppe route further north, from Urumqi across the Dzungarian Gate to Almaty, Astrakhan, Kazakhstan and on to Russia and the Caucasus

- Part of this is the route the Chinese government proposed as their first Silk Road entry on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

- visiting other great cities of the Persian Empire: Herat, Isfahan, Shiraz (Persepolis)...

- swinging north from Iran into the Caucasus

- crossing the Caspian Sea by cargo boat, usually from Turkmenbashi to Baku

- crossing the Black Sea by boat, often from Batumi, Poti or Trabzon to Odesa, Sevastopol, Varna or Istanbul

Overall, the "Silk Road" was never a single road, more a web of roads and caravan trails linking dozens of cities.

Related routes

[edit]

Various related routes connected China to the Indian subcontinent:

- South from Xinjiang into Pakistan and India via what is now the Karakoram Highway or via Ladakh. For centuries Taxila was the main terminus on the Indian end of these routes.

- Into Afghanistan via Bactria from points further west on the road, then perhaps:

- to what is now central Pakistan via the Khyber Pass

- to Balochistan and Sindh via the Bolan Pass

- A "Tea and horse caravan" route much further south, from Chengdu through Yunnan and parts of Tibet to Burma and northern India

- The Sikkim Silk Route connected Tibet to eastern India. The only border crossing open today between China and India is on this route – though open only to traders, not to tourists.

Further west, the Incense Route brought frankincense, myrrh and other goods from Oman and Yemen, overland via what are now Saudi Arabia and Israel, to the Mediterranean countries. See Mitzpe Ramon#Trails for one part of that route.

Maritime Silk Road

[edit]By no means all trade went by the overland caravan trails; there was also a great deal of traffic by sea.

Not all of the history is known and historians disagree on parts of it, but it is clear that this trade is quite old and quite wide-ranging. By 2000 BCE some trade routes were well established, between the Indus Valley Civilization and Ancient Mesopotamia via the coast of the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, and the maritime jade route carrying trade over most of Southeast Asia.

Greek records show that routes between the Red Sea, East Africa and what is now the west coast of India were well known a few centuries BCE. Chinese records show traders sailing to India via Indonesia in the third century CE, and it seems likely that trade started centuries earlier. Ptolomey of Alexendria created maps for both land and sea routes to China in the second century CE.

In China, the main ports for this were Guangzhou and Quanzhou. Marco Polo sailed home from Quanzhou and described it as the busiest port on Earth and fabulously wealthy. Ibn Battuta both arrived and departed via Quanzhou.

Further west, the great ports included Malacca in the Straits of Malacca, Rangoon and Chittagong in the Bay of Bengal, Cochin and Calicut on the South Indian coast, Cambay further north in India, Karachi in Pakistan, Basra in Iraq, Muscat in Oman, and Aden in Yemen. Alexandria was this route's gateway to the Mediterranean; Polo considered it the world's second busiest port.

Some words in modern English come from the ports on this route from which certain items first reached Europe: "satin" is from Zaiton (the Arabic name for Quanzhou), the "macassar" hairdressing oil is from Makassar in Sulawesi island, and "calico" from Calicut. Bactrian camels (two-humped, as opposed to Arabian camels, which have a single hump) are named for the inland Silk Road region, Bactria. Similarly, the nutmeg's standard name in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Dutch, German and Russian is "nut from Muscat", even though originally the only source was the Spice Islands in what is now Indonesia.

Grapes were introduced to the Mediterranean region either from the Middle East or the Black Sea, and Muscat grapes were among the earliest, having been grown in Ancient Greece. Some experts suggest they are original seed stock from which all modern grapes derive, and some think they are named for the city of Muscat, though neither claim gets unanimous agreement. Muscat grapes are fermented to produce a sweet wine called Moscatel or Moscato. The oldest evidence of winemaking has been found in Iran, and wine spread outward to Europe, Georgia, and China (the famous poet Li Bai was known as one of the "Eight Immortals of the Wine-Cup" for his incessant drinking).

During the reign of Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty, Chinese-Muslim Admiral Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho) would sail on voyages that took him to Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East and even as far as Mogadishu in East Africa. His contact with the Malacca Sultanate in what is today Malaysia led to the first wave of Chinese immigration to the area, where many intermarried with the local Malays to give rise to the Peranakan community, whose unique culture and cuisine endures to this day. Until the Emperor shut down all seaborne foreign trade in the 1420s, there was regular trade between China and ports as far West as Aden on both Chinese and other ships. Even after the shutdown, the emperor allowed Zheng He to sail to Jeddah for his Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca.

The first Muslim missionaries reached China by sea in the 7th century, and several Chinese cities had mosques built during the Tang Dynasty, i.e. before 907. By around 1000 CE, Quanzhou had a substantial community of Arab and Persian residents, and the Great Mosque there (not the first) was built in 1009.

In the 1980s, an Englishman named Tim Severin had a replica of a 9th century Arab dhow built in Oman and, with an Omani crew, sailed it all the way to Guangzhou. The ship is now back in Oman and on exhibit. See Severin's Wikipedia entry or his book The Sinbad Voyage for details.

In general, Asians were doing extensive trade over these routes centuries before Europeans turned up. When Vasco da Gama (en route to becoming the first European to reach India by sea) reached East Africa via the Cape Route in 1498, he found Chinese trade goods such as blue and white pottery already well established in the market. This made sense at the time; medieval Europe was insignificant on the world stage and the Americas were not yet "discovered" while Asia produced most of the world's wealth and had most of its trade.

One of the finest examples of the sheer globalness of trade in the pre-Industrial age is the temple at Borobudur. Along the walls of the temple are many friezes, some of which chronicle foreign trading ships. There is also a section that chronicles trade between the Majapahit (controlling Sumatra, Java, and some parts of neighboring regions) and the Chola kingdom in southern India and Sri Lanka; one of the most famous reliefs from the structure depicts the "Borobudur Ship", highlighting the role of the Maritime Silk Road in the region.

Later, Europeans had huge influence in the region. One significant change was colonisation — Russia in Central Asia and Northeast China, the United Kingdom in India, Malaya, northern Borneo, Burma and Hong Kong, Portugal in Goa, Macau and East Timor, France in Pondicherry and Indochina, the Netherlands in what is today Indonesia, Germany in the Shandong Peninsula, and first Spain then later the United States in the Philippines. There were also large changes in trade routes; some of the most important were huge imports of silver from Spanish Mexico to Spanish Manila and thence into East Asia, and the extensive three-cornered trade involving tea clippers mainly from China to Britain and opium mainly from British Bengal into China.

In the 21st century, China has sought to revive and expand the Maritime Silk Road through the Belt and Road Initiative, through which they have invested in building ports in far-flung corners of the globe such as the Persian Gulf, Africa and Latin America. In Thailand, there has been talk of building a shipping canal across the Isthmus of Kra in Southern Thailand with funding from China, allowing ships travelling between China and Europe or India to bypass Singapore and save several days of time and millions of dollars worth of fuel in the process, though these have been repeatedly held back by concerns over ethnic Malay Muslim separatists near the Malaysian border.

Sleep

[edit]The traditional inns of the area are called caravanserai. They are built around a walled courtyard and have stables for the horses and camels. Most were in towns but there were also some rural ones, often fortified against the local bandits.

Some caravanserai still exist; anyone traveling this road should try to find them and stay in them at least once.

One group of caravanserai have been designated a ![]() UNESCO World Heritage Site; see The Persian Caravanserai.

UNESCO World Heritage Site; see The Persian Caravanserai.

Other than caravanserai, most visitors will stay in hotels, hostels, or homestays. Homestays are especially popular in Central Asia, where countries like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan promote them.

Whether or not you can camp depends on where you are and the local government's policy towards passport controls. In many countries along the Silk Roads, you need to "register" your passport every so often (pretty much every hotel/hostel will do this for you upon check-in), so long-term camping (usually more than 3 days) is next-to-impossible. The only place on the Silk Road where you have to camp is at Darwaza in Turkmenistan, because there are no hotels or hostels.

Stay safe

[edit]Historically, many of the people in this region have been nomadic herdsmen, some still are, and even in the cities tribal loyalties may run strong, which implies at least:

- a tremendous tradition of hospitality

- suspicion of outsiders, even from neighboring tribes.

- (Foreigners are sometimes exempt.)

- considerable hostility toward both Western and Russian influences

- many of them are heavily armed

The whole area along the overland route, except a few parts of China, is Muslim which implies at least:

- a tradition of Muslim hospitality and wonderful treatment of visitors

- some conservatism, especially in matters such as women's clothing

- risk of foreigners who do not understand Islam giving offense

In this area, the politics get very complicated, with tribal, ethnic and religious issues all adding to the complexity. Moreover, the collapse of the Soviet Union left some of the area's governments in a chaotic state from which they have not entirely recovered. Tajikistan underwent a horrible civil war from 1992-97, and periodically ethnic tensions flare up in the Pamir region. Uzbekistan was a police state until 2018 (and is still heavily bureaucratic). Turkmenistan, for example, is about as authoritarian as North Korea. Iran is a safe country (for the traveller), but its poor relations with many Western governments means that travellers might be on their own if situations arise.

As of early 2019, there has been active warfare for several years in various areas along the route — Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, several Caucasian areas with Chechnya the best-known, and Yemen on the Maritime Silk Road — and potential conflicts in several others. Drone attacks by US forces are frequent in Yemen and in Northwest Pakistan. Avoid these areas, or see War zone safety if you must go.

As along other trade routes, there is a long tradition of banditry along the Silk Road. This has been vastly reduced over the past two centuries, but there may be risk of new outbreaks when an area becomes chaotic. There are also complications associated with the drug trade; in the last few decades, Afghanistan has become a major source of opium (the raw material for morphine and heroin manufacture); much of it is smuggled north through neighbouring countries then along old Silk Road routes toward Russia and Europe. Piracy does occur in the Gulf of Aden and Southern Red Sea. If you are using the Maritime Silk Road, be cautious of this.

All that said, with a bit of common sense and goodwill, a willingness to route around trouble spots, and a lot of flexibility on the part of the traveller, the risks are generally quite moderate.

See individual country and city listings for more. Roads are poor in many areas and some are impassable in the winter or monsoon season. Various mountain and desert areas can be quite dangerous if appropriate care is not taken. Also, most locals are friendly, curious and helpful, but the traveller needs some understanding of local customs and must take some care not to give offense.

In some parts along the Silk Roads, the environment can be your worst enemy. Most of Central Asia is dominated by two massive deserts which, in addition to the heat and dehydration dangers they pose, also kick up huge dust storms that can affect places as far away as the Ferghana Valley and Baku. Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Afghanistan are all highly mountainous countries, and avalanches and rockslides can happen at any time. Earthquakes are also relatively common in the region, and can damage infrastructure or cause other natural disasters. In China, the huge Taklamakan desert is nearly devoid of both water and settlements. If travelling through the region, make sure you have enough supplies (water, gas) to get from town to town.

Along the Maritime Silk Roads, tropical storms, monsoons, and cyclones can all put a serious damper on your sea voyage. Make sure you (or people you're travelling with) know how to handle a ship during a storm (and avoid them if you can).

See also

[edit]- Islamic Golden Age

- Imperial China

- Persian Empire

- Mongol Empire

- Russian Empire

- Western Xia

- Voyages of Sven Hedin

- Mughal India